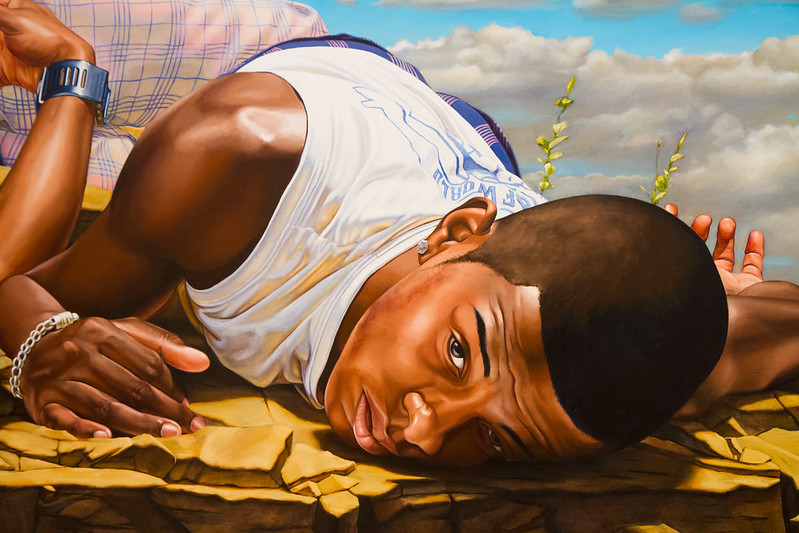

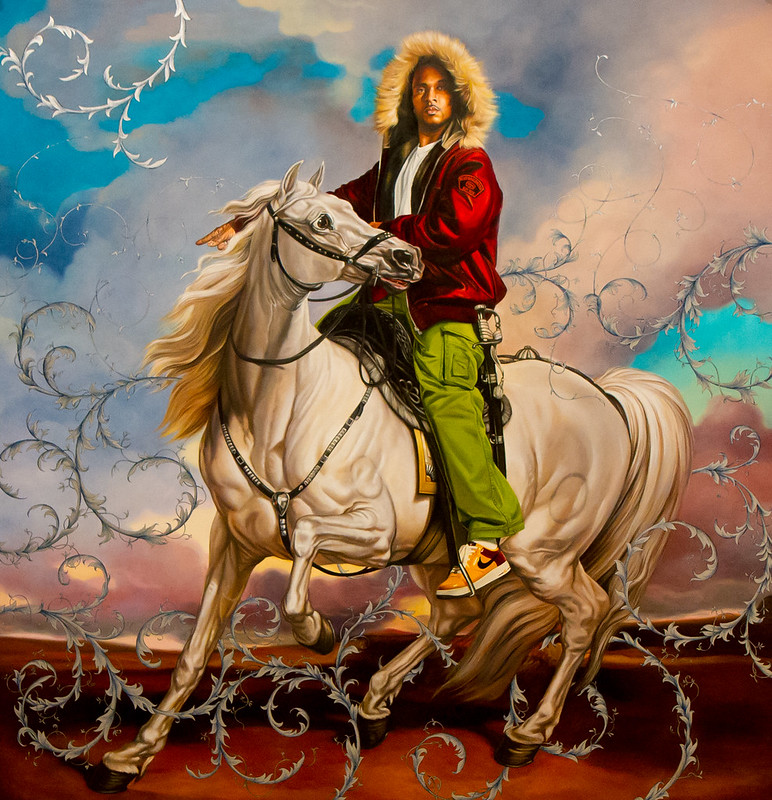

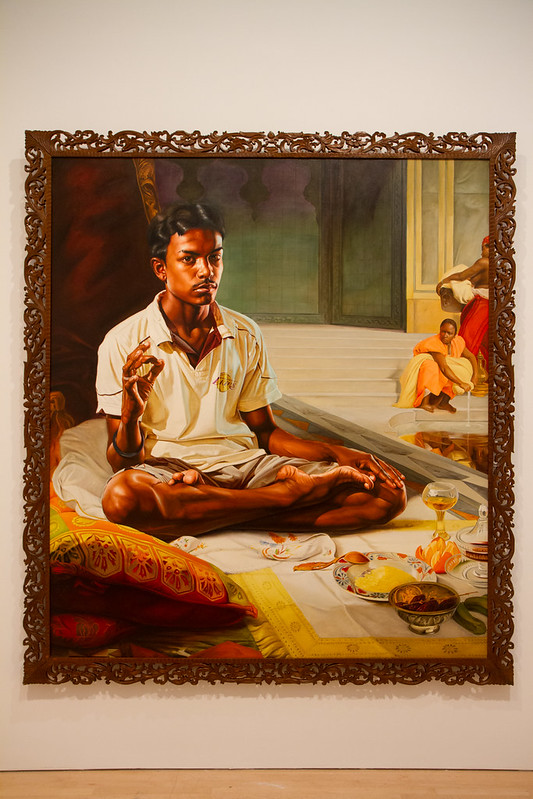

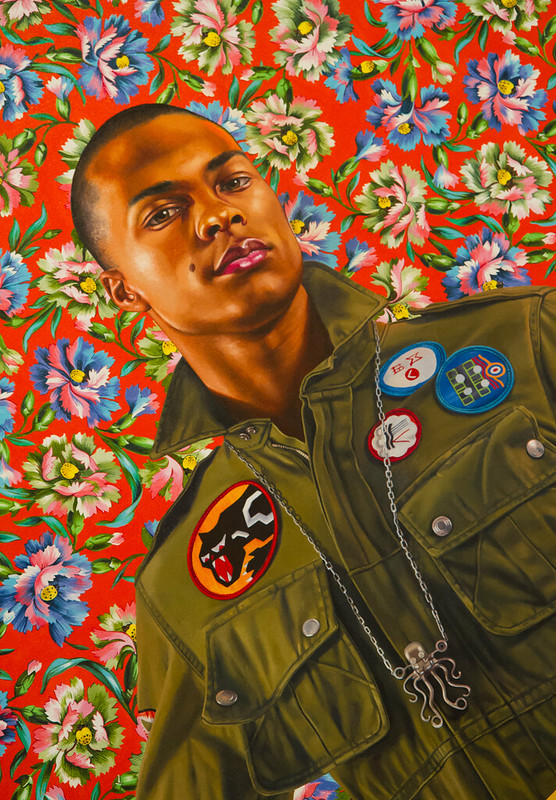

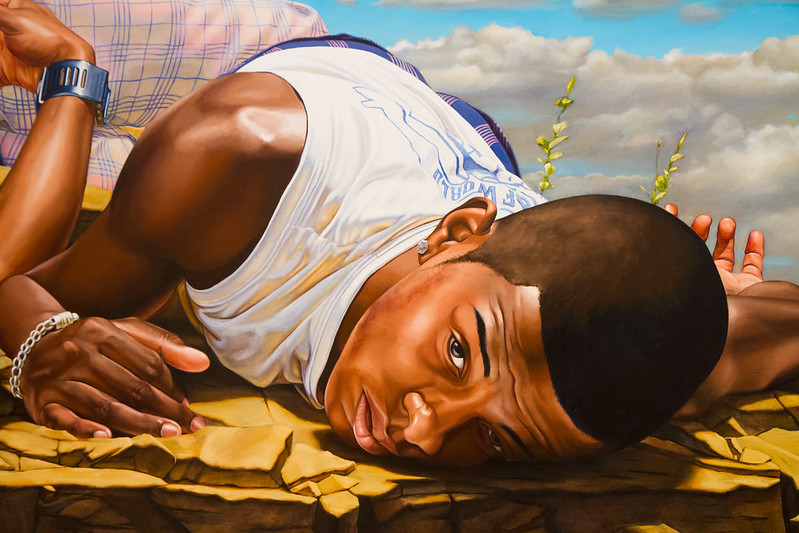

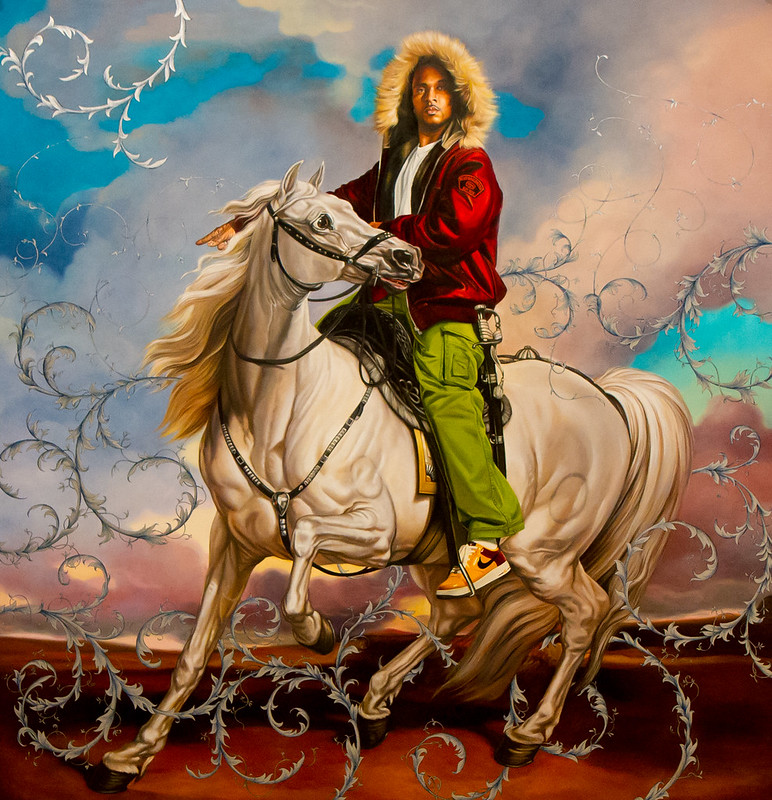

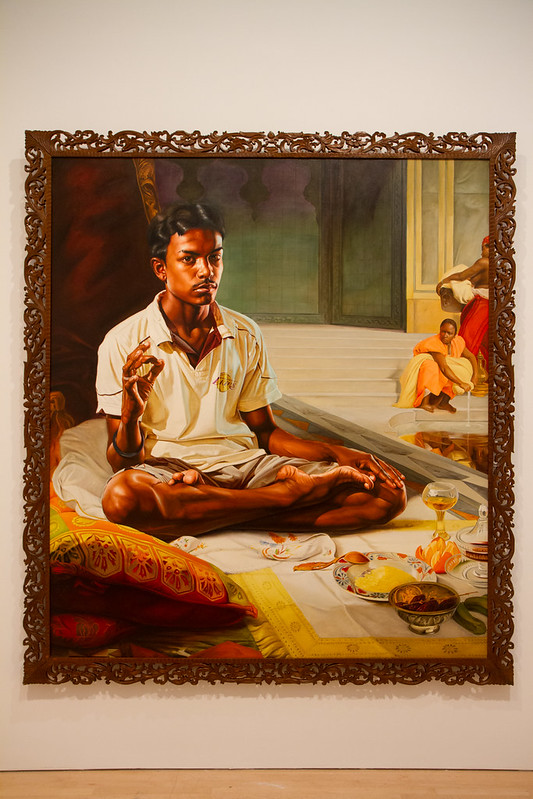

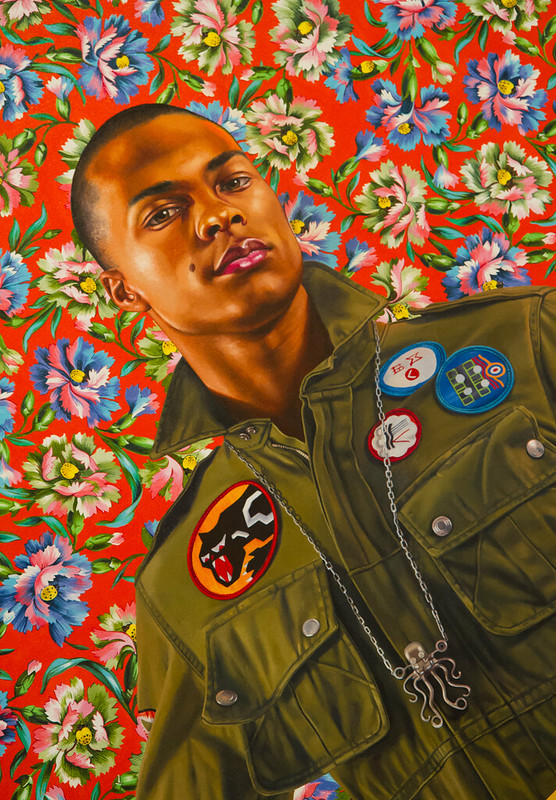

Kehinde Wiley, A New Republic, Brooklyn Museum

[draft]

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

Kehinde Wiley, A New Republic, Brooklyn Museum

[draft]

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

New York, N.Y. From its humble beginnings in the bustling streets of Moscow, the Moscow Circus has evolved into a breathtaking spectacle that has enthralled audiences worldwide. We envision the origins of this grand enterprise, a small troupe of daring performers who dared to dream big, defying gravity and pushing the boundaries of what was possible. However, as we look back on the decades-old tradition, a pressing question emerges: in the 2020s, is it fair to the animals?

Historically, the Moscow Circus has been more than just entertainment; it’s been a cultural ambassador, a bridge connecting diverse cultures through the universal language of artistry. The inherent beauty in the performers’ movements, the harmonious blend of strength, grace, and precision defines their craft. Every act is a symphony of skill and creativity, a testament to the unwavering dedication and rigorous training that lies behind each performance. Yet, among the dazzling human feats, tigers jumping through flaming hoops, famous Russian dancing bears, performing seals, and elephants raise ethical concerns.

We witness a world where gravity is defied, where the impossible becomes possible, and where the audience is transported to a realm of wonder and awe. The performers, with their unwavering focus and breathtaking feats, embody the very essence of human ambition and determination. However, the inclusion of animals in these spectacles prompts us to consider their well-being and rights.

We recognize the profound impact the Moscow Circus has had on the world. It has not only entertained millions but has also ignited a passion for performance arts, inspiring countless aspiring artists and performers around the globe. It is a living testament to the power of the human spirit to overcome seemingly insurmountable obstacles and achieve the extraordinary. Yet, it is crucial to address whether the pursuit of entertainment justifies the involvement of animals, whose training often involves practices that are no longer acceptable by today’s ethical standards.

Every act carries with it the legacy of generations of performers, each contributing to the rich tapestry of this enduring institution. The stories whispered through generations, the shared knowledge and dedication passed down like a sacred flame, fuel the passion and artistry that define the Moscow Circus. But with evolving societal values, this legacy now faces scrutiny regarding animal welfare.

We are particularly drawn to the unique blend of traditional Russian artistry and contemporary innovation that characterizes the Moscow Circus. It is a harmonious fusion of the old and the new, a testament to the enduring power of tradition while embracing the possibilities of the modern world. This dynamic blend resonates with audiences worldwide, appealing to a diverse range of tastes and cultural sensibilities. However, this blend must also reflect contemporary ethical standards, ensuring that all performers, human and animal alike, are treated with dignity and respect.

The Moscow Circus serves as a platform for cultural exchange, a vibrant space where artists from different backgrounds and disciplines come together to create something truly unique and unforgettable. The diverse cast of performers, each bringing their unique skills and talents to the stage, embodies the spirit of unity and collaboration that defines this extraordinary institution. But as we celebrate this unity, we must also advocate for the humane treatment of animals, ensuring that their welfare is not sacrificed for the sake of tradition.

The Moscow Circus has not only entertained generations but has also inspired a sense of wonder and amazement in its audiences. Its legacy transcends generations, leaving an indelible mark on the hearts and minds of those who have experienced its magic. We are grateful for the boundless joy, the sense of awe, and the inspiration that the Moscow Circus has brought to the world. As we move forward, let us also strive to ensure that this joy and inspiration come without compromising the well-being of any living being, recognizing that true artistry respects the rights and dignity of all its participants.

Exploring Art, Tradition, and Ethical Dilemmas of Moscow Circus (July 18, 2016)

TAGS: Circus Arts, Global Culture, Entertainment, Human Potential, Tradition, Innovation, Performance Art, Animal Welfare

[draft]

New York, N.Y. I actually grew up on the banks of the Ohio River. Nothing sent chills through my spine as a child than the calliope of the Delta Queen docking near our home.

Slice of Americana: The Delta Queen in Cincinnati (June 26, 2016)

Wright, Joseph: Moonlit Landscape

Moonlit Landscape, oil on canvas by Joseph Wright, 1793. 63.5 × 82.5 cm.

[draft]

[draft]

April 2007

Opening Sri Lanka House Outside Galle

Photo: Owning a home might not seem “poor,” but a simple home versus a mansion provides sanctuary, not excess.

[draft]

xxx

Photo: Slave ship chains of the Transatlantic route.

http://stewardshipreport.com/slavery-remembrance-day-u-n-shines-light-on-african-diaspora-legacy/

On Slavery Remembrance Day, U.N. Shines Light on African Diaspora Legacy (June 20, 2016)

Photo: Stephane Duret stars in Kinky Boots on Broadway.

#StephaneDuret #Stars on #Broadway in Hysterical #KinkyBoots premier won #LaurenceOlivierAwards

http://www.stewardshipreport.com/stephen-duret-stars-on-broadway-in-hysterical-kinky-boots/

Stephane Duret Stars on Broadway in Hysterical Kinky Boots (June 20, 2016)

[draft]

New York, N.Y. Berta Cáceres was a force of nature, a fearless defender of indigenous lands and a tireless champion of environmental justice. Her brutal assassination on March 2, 2016, at the age of 44, sent shockwaves around the world, but her legacy as a global citizen and thought leader lives on.

Her courageous stance against the Agua Zarca dam earned her the prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize in 2015, solidifying her status as a thought leader in the fight against corporate exploitation and environmental degradation.

As a member of the Lenca indigenous community in Honduras, Berta was deeply connected to the land and its sacred rivers.

Her unwavering opposition to the Agua Zarca hydroelectric dam project, which threatened to displace her people and desecrate their ancestral territories, made her a target for powerful corporate interests and corrupt officials.

Despite constant threats and intimidation, she remained resolute, leading peaceful protests and garnering international support for her cause. Berta’s activism transcended borders, inspiring a global movement to protect the rights of indigenous communities and safeguard the environment.

She believed that the struggle for environmental justice was inextricably linked to the struggle for human rights and dignity. Her words resonated with people from all walks of life, reminding us of our collective responsibility to protect the planet for future generations.

Her family and the Council of Indigenous Peoples of Honduras (COPINH) continue to carry the torch, demanding justice and accountability for her murder while advocating for the rights of indigenous communities worldwide. Her name has become a rallying cry for environmental defenders across the globe, a symbol of resistance against corporate greed and state-sanctioned violence.

As global citizens, we stand in solidarity with Berta’s vision of a world where indigenous rights are respected, where the voices of marginalized communities are amplified, and where our planet’s precious resources are protected for generations to come.

Her life and her ultimate sacrifice serve as a powerful reminder that the struggle for environmental justice is a struggle for human rights, and that we must all be willing to stand up and fight for what is right, no matter the cost.

In Memoriam: Berta Cáceres, Honduran Martyr for Environmental Justice (June 14, 2016)

Image: Map of the Japanese Diaspora. Wikipedia.

Jim Luce attended the International Division of Waseda University. He taught with the Japanese Department of Education in the north of Honshu. His first job was with a Japanese bank on Wall Street.

ジム・ルースは早稲田大学国際部に通いました。彼はまた、東北 の 文部省 で教鞭を執りました。彼の最初の仕事はウォール街の日本の銀行でした。

Jim Luce Writes in Japanese Translation | ジム・ルースが日本語訳で執筆

Follow Jim Luce on Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, TikTok, and X (Twitter).

© 2024 The Stewardship Report on Connecting Goodness – Towards Global Citizenship is published by The James Jay Dudley Luce Foundation Supporting & Educating Young Global Leaders is affiliated with Orphans International Worldwide, Raising Global Citizens. If supporting youth is important to you, subscribe to J. Luce Foundation updates here.

Activism Asia Authoritarianism Children China Civil Rights Climate change Democracy Diplomacy Donald Trump Education Equality Gaza Geopolitics Global citizen Global citizenship Haiti History Human rights Immigration India Indonesia International Law International Relations Israel J. Luce Foundation Jim Luce Leadership LGBTQ+ Mental health New York New York City Orphans International Orphans International Worldwide Philanthropy Politics Russia Social justice Sri Lanka Thought Leader Trump Trump administration Ukraine United Nations World War II

With my mom at Rockefeller Plaza, Easter, 1992. So many gay men then were dying of AIDS and we wore red ribbons in their honor.

GoodNewsPlanet: @LuceFoundation 16th Annual #Leadership #Awards Reception. @LionsClubs http://goodnewsplanet.com/16th-annual-leadership-awards-reception-2/

16th Gala at St. John’s (April 10, 2016)

Photo: Presenting our Foundation’s Global Citizenship award to H.E. Katalin Bogyay of Hungary. Credit: Derek Balarezo/Stewardship Report.

New York, N.Y. Over 700 people from all walks of life assembled in a large conference room in the United Nations headquarters last weekend to celebrate the International Day of Happiness. A U.N. resolution officially proclaimed March 20 as the day to annually recognize the importance of happiness in the lives of people worldwide. Since 2013, events have been organized around the world.

A marathon full-day event at the U.N. was organized by Ambassador Angelo Toriello of the Permanent Mission to the U.N. of São Tomé and Príncipe and Special Envoy of the President of the country, Manuel Pinto da Costa.

The U.N. Missions of the Republic of Palau and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam were co-sponsors. Ambassadors from many other countries were present.

The focus was on honoring healthy people and a healthy planet as fundamental to happiness, goals intertwined with the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted by the U.N. General Assembly last September.

Consequently, the theme was “Happiness and Well-being in the U.N. 2030 Agenda: Achieving a New Vision of Sustainable Development for the People and the Planet.”

The event featured inspiring presentations intermixed with cultural performances that were so compelling that many people who had arrived at 8am stayed for twelve hours, until the final performance.

“At this time of grave injustices, devastating wars, mass displacement, grinding poverty and other man-made causes of suffering, the International Day of Happiness is a global chance to assert that peace, well-being and joy deserve primacy,” U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said in his official message on International Day of Happiness.

The Secretary-General conveyed his personal wishes to everyone to enjoy the event when meeting with Shweta Emmanuel Inderyas, Executive Assistant and spokesperson in Ambassador Toriello’s office in India that represents President Manuel Pinto da Costa in the Asia region.

The video of mobile game characters “Angry Birds” was played, given that the Secretary-General appointed Red as an honorary ambassador to raise awareness about addressing climate change for a happier future.

The event was presented by Humanicy – Ambassador Toriello’s initiative to bring the human side into diplomacy – as a tribute to the Kingdom of Bhutan, a country whose King started the focus on happiness in 1972. Bhutan has proposed a new paradigm of development to include Gross National Happiness as opposed to just Gross National Product.

Ambassador Toriello welcomed the assemblage and often joined in the conversation and merriment. His spontaneous singing of That’s Amore drew much applause.

UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador to Nepal Ani Choying Drolma, a Buddhist nun who traveled from Nepal for the event, launched the ceremony with sacred chants.

In his welcome message, the President of the U.N. General Assembly, H.E. Mogens Lykketoft, said that as a native of Denmark, he was particularly happy that his country had previously been rated by the Happy Planet Index as the happiest nation in the world, noting that everyone in his country has been given access to education, health and protection.

He noted that “by the SDGs, we have set ourselves a deadline to make the right of a good life a reality for everyone.”

The first panel featured ambassadors from countries that have played a major role in the promotion of happiness and well being at the United Nations.

H.E. Ambassador Kunzang C. Namgyel, Permanent Representative of the Kingdom of Bhutan to the U.N., expressed appreciation for the Humanicy tribute to her Kingdom, and noted that a growing number of countries and civil society organizations are starting to question the way we measure happiness and recognizing happiness as fundamental to human existence.

Ambassador Otto addressed the crowd with touching remarks about how Palauans view life from the heart and emphasized the importance of the spiritual realm in development. His wife Judy, a public health expert who enjoyed the event all day, was a partner in its organization.

H.E. Ambassador Nguyen Phuong Nga, Permanent Representative of the Mission of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam to the U.N., described her country’s national motto of independence, freedom, and happiness. “The 2030 agenda is our guideline to make the world a happier place where no one is left behind,” she said.

The theme of “Happy People Happy Planet” was highlighted by an original anthem with that refrain brilliantly composed for the occasion by international musician/composer Russell Daisey.

As Russell and his back-up choir sang, more serious messages of the day turned to spontaneous delight when soft stuffed globes mapping the world – from eight inches to two feet wide – representing the planet, were tossed throughout the auditorium and hugged by ambassadors and audience alike.

It was a spectacle I had never witnessed in my almost two decades at the United Nations. The globes were donated by Hugg-A-Planet founder Robert Forenza.

The event was also an acknowledgement of H.E. Ambassador Dr. Caleb Otto, Permanent Representative of the Republic of Palau to the United Nations, who was responsible for the inclusion of mental health and well-being in the new U.N. global agenda.

In her keynote address on “Wellbeing in the U.N. 2030 Global Agenda,” event producer and noted international psychologist Dr. Judy Kuriansky described this campaign and her partnership with Ambassador Otto in this historic effort, demonstrated in the video shown about “Youth and Mental Health: Youth and Ambassadors Speak Out.”

Dr. Judy, who had been invited to the 2012 U.N. high-level meeting organized by Bhutan about a new paradigm of development, was a keynote speaker at the first U.N. panel on the International Day of Happiness in 2013.

“What a wonderful day when happiness, mental health and well-being were united,” said Ambassador Otto, echoing the many enthusiastic comments about the day.

Noted humanitarian Ms. Man Xian Li, Founder of the American Oriental Arts Foundation, took the stage to offer gracious appreciation of the bridge between cultural arts and the celebration of happiness in joyful as well as serious ways.

In another of the many emotionally touching moments to me, that I could feel moved the audience to be connected and happy, Ambassador Toriello invited the audience to hold hands in a show of solidarity and caring.

Celebrity actor “007” Daniel Craig was on hand to join the celebration. Daniel was named by the Secretary-General as U.N. Global Advocate for the Elimination of Mines and Explosive Hazards. Film star Craig graciously greeted the crowd and U.N. dignitaries.

The Deputy Permanent Ambassador of the Mission of India to the U.N., H.E. Ambassador Tanmaya Lal, reminded everyone that we all have a responsibility to work together to make this planet sustainable and to achieve harmony.

Former Director of the Central Bureau of Investigation of India, and Director General of the National Human Rights Commission, H.E. D.R. Kaarthikeyan, underscored how the progress of a nation should be judged by happiness and not just a growing economy. The noted law enforcement officer organized the First World Parliament on Spirituality.

The two exceptional MCs wove the innumerable pieces of the program together with not only professionalism and aplomb but also good humor.

Alizé Utteryn, born in French Guyana, is a former model and currently publishe of AlizéLaVie magazine.

Shannon LaNier, television reporter for Arise TV, is also author of the book Jefferson’s Children: The Story of One American Family about uncovering his heritage as a ninth generation descendant of Thomas Jefferson and slave Sally Hemings.

Culture was interspersed throughout. Virtuoso of the ancient Chinese instrument erhu, Feifei Yang and pipa virtuoso Jiaju Shen played a medley of tunes, including Pharrell Williams’ Happy.

In a keynote Address, Dr. Dan Haybron, professor of philosophy at St. Louis University, described his visit to Bhutan to consult about the Gross National Happiness survey.

It was most surprising to me that Bhutanese rated a high number of people they could count on.

I was also impressed that Haybron was awarded a $5.1 million grant from the Templeton Foundation for a three-year project to encourage young researchers on the topic of “Happiness and Well-Being: Integrating Research Across the Disciplines.”

Other U.N. ambassadors spoke on what happiness means to them and their nations. H.E. Jean-Francis Zinsou of the Mission of the Republic of Benin to the U.N. noted in his typical eloquence that happiness is about being free of want, fears, and threats of any kind.

In his role as the Global Coordinator of the Group of Least Developed Countries during the global agenda negotiations, Ambassador Zinsou had been exceptionally supportive of the importance of well-being.

H.E. Barlybay Sadykov, Deputy Permanent Representative of the Republic of Kazakhstan to the U.N., emphasized how happiness is fundamental to the achievement of world peace, to which his country is dedicated.

H.E. Ambassador Katalin A. Bogyay, Permanent Representative of the Mission of Hungary to the U.N., made me – and everyone – smile when she noted that happiness begins with a smile.

Her experience as a journalist and television reporter was evident in her presentation engaging the audience.

After her address, it was my honor to present Ambassador Bogyay with the J. Luce Foundation Global Citizenship Award.

Ambassador Bogyay told me after the event:

“I was delighted to have had the chance to speak at this wonderful event.

It was great to see that in spite of the horrendous things the world is experiencing today, members of the international community and civil society took time to celebrate the International Day of Happiness and the commitment towards universal well-being that is embodied in the 2030 SDG Agenda.”

“Moreover, I felt honored to receive the 2016 Global Citizenship Award of the Luce Foundation on this joyous occasion. I am a firm believer that happiness is something we create and not wait for. Happiness is something we aim and work for; happiness is a constant curiosity, challenge and action.

“I am a diplomat who believes that multilateral and cultural diplomacy can help indeed in bridging people, and if we do it well, it can give us a chance at least to try not to misunderstand but understand each other.

Having once been imprisoned in his native country, former Ambassador of Iraq to the U.N. Hamid al-Bayati knows the value of well-being. A professor and author of books like “From Dictatorship to Democracy: An Insider’s Account of the Iraqi Opposition to Saddam,” he had spoken on the panel at the first International Day of Happiness here at the U.N. in 2013.

Teacher Betsy Sawyer was surrounded by her dedicated students who described their dream project The Big Book: Pages for Peace with great pride. The massive book measuring twelve feet tall by ten feet wide, was displayed in the lobby, marking its first stop in a planned 2016 World Tour. I was in awe.

The Big Book, begun in 2004, weighs more than a ton (!) with contributions from more than 3,500 notables, including 9/11 First Responders, Nelson Mandela, Jimmy Carter, and the Dalai Lama. The students obviously touched everyone’s heart when talking about how anyone can achieve their dream as they did, and that their “dream goes on.”

It was a big surprise to all when a video was played of famed Italian comic actor Totò — considered an heir of the Commedia dell’Arte tradition — and then onstage he walked! But he had died in 1967. Aha!

Under the mask, was Amerigo Festa, president of the Italian organization United Beings, in full regalia dressed as Totò, the stage name of Prince Antonio Griffo Focas Flavio Angelo Ducas Comneno Porfirogenito Gagliardi De Curtis di Bisanzio. Festa is promoting a movement to have a Minister of Peace in all nations.

In a passionate narrative, Greek native Georgia Nomikos of the Orpheus Luxury Collection, spoke about the many contributions of her people to the welcome and well-being of refugees to the Greek islands.

As president of the J. Luce Foundation and Orphans International Worldwide (OIW), I presented the next keynote address, moderating a panel of Lions Clubs International members,”Happiness Through Service.”

It was a new experience for me to speak of my personal experience in giving up my savings from my family and made on Wall Street — to disavow money and devote my energy to helping orphans worldwide, including adopting my cherished son Mathew James Tendean Luce from Indonesia.

Lions District 20-R2 Governor Guillermo A. Perez spoke about the 1.4 million Lions in 200 countries around the world actively engaged in service, often for the sight-impaired.

Student Hector Liang, president of the New York Tribeca Campus Lions Club at Borough of Manhattan Community College, also spoke with great passion on his club’s activities to serve humanity. Kevin Camacho, District Zone Chair and past president of the Tribeca Club, also spoke on finding happiness through helping others.

Our own club, the New York Global Leaders Lions Club (NYGLLC), was founded specifically to engage in service. The Lions had just celebrated Lions Day at the U.N., which I attended and wrote about (here).

True to the theme of “Humanicy,” the event included many speakers with expertise in human development. Holistic coach and energy medicine expert Sonia Emmanuel described how the experience of happiness and love releases hormones that vibrate at the highest frequency.

Many speeches from Italian experts addressed the science and practice of positivity, wellbeing and happiness. Neurologist Dr. José Foglia, M.D., Ph.D., presented a new paradigm of neuroscience taking kindness into account, entitled “Homolux.”

Other speakers included Stefano Bizzotto representing the Italian group known as Conacreis, who spoke about holistic energy treatments; spiritual healer Crótalo Sésamo (born Alessandro Zattoni) who teaches astral traveling and out-of-body experiences, representing the ecovillage and spiritual community of Federazione Damanhur; representatives of United Beings in Italy, holistic therapist Patrizia Coppola with ReiKi master and entrepreneur in ecological wellness Roberto Cossa; and filmmaker Nicolas Grasso.

For someone so young, Francesca Festa truly inspired me by telling her heartfelt story about how she came to devote her life to founding a movement that promotes saving exotic wildlife.

Many people wonder whether happiness can be measured, so it was truly educational to hear Michelle Breslauer of the Institute for Economics and Peace talk about measuring peacefulness through the Global Peace Index.

Meditation is key to peacefulness. The Field Resonance Medit-Action was a 21-Minute experience in which all the participants in the Hall, “in Resonance and in Communion of Intent,” joined with individuals and groups around the world to generate a “Field of Anticipated Joy and Gratitude” that was said to “reach, envelope, and fill all Humanity.”

Treating us to more sheer entertainment and brilliant performance, raising all of us to our feet dancing and waving arms, composer/pianist Russell Daisey and his band and choir played a medley of music on the theme of happiness.

The popular songs included “Here Comes the Sun,” “Happy Days Are Here Again,” “Don’t Worry, Be Happy,” “What a Wonderful World,” and “Oh, Happy Day.”

Daisey is also a representative of the ECOSOC-accredited NGO, the International Association of Applied Psychology, that also partnered in the event production.

As if I wasn’t already enthralled and awed, more cultural art was in store with a dance performance by Nalini Rau, founder of the Natya Anubhava Academy of Classical Dance, with one of her star high-school students, Meena.

I can’t remember having ever spent twelve hours with over 700 people of such goodwill assembled to uplift humanity – which is exactly what we did at the United Nations headquarters last week celebrating the International Day of Happiness.

The intergenerational duo offered a classical Indian dance performance interpreting the “essence of being.”]

Naturopath Giuseppa Camerino sang a devotional song, “Nirvanasatkam,” which was a perfect prelude into a concert by UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador to Nepal Ani Choying Drolma and her band in a series of Buddhist chants set to contemporary music played on classical instruments.

The performance closed the International Day of Happiness at the United Nations on a perfect uplifting note after a most exciting, educational and inspirational day, which I thought brought a special spirit to the United Nations.

Global Citizens and thought leaders Ambassador Angelo Toriello, Ambassador Dr. Caleb Otto, and Dr. Judy Kuriansky — and so many more — are to be commended for making the world a better place. I intend to be front row center next year – and bring all of my friends!

Jumping for Joy: Happiness Day 2016 at the United Nations (March 29, 2016); originally published in The Huffington Post.

This is designed to be lightweight, reversible, and respectable—not hustle-y.

1. Account & Imprint Setup (One-Time)

Amazon KDP Account

Publisher Identity

We are not positioning this as a mass-market children’s brand.

We’re positioning it as a mission-aligned cultural imprint.

2. Formats to Use (Keep It Simple)

For each book:

✅ Paperback (Primary)

⛔ Hardcover (For Now)

⛔ eBook

Rule: Fewer formats = less stress.

3. ISBN Strategy

4. Book Metadata (This Is Where You Win)

Categories (Choose 2–3 max)

For stories in the And It’s Okay Series:

For The Special World of Mathew James:

For Make Way for Shih Tzu:

Keywords (7 slots)

Think: how parents and educators search.

Example:

5. Pricing (Low Pressure, Respectable)

Paperback Pricing

We are not optimizing for profit.

We are optimizing for credibility and accessibility.

6. Launch Style: The Quiet Launch

This is key.

Instead:

You can always relaunch later with:

Publishing is not a one-time moment—it’s a state of being.

7. What Luce Publications Becomes (Without Forcing It)

Over time, Luce Publications quietly becomes:

No rush. No brand inflation. Just presence.

Part II: “About the Author” (One Paragraph)

Here are versions that work everywhere—Amazon, press, foundations, and websites.

About the Author

Dr. William M. (Bill) Bauer is a licensed clinical counselor in the rural Mid-Ohio Valley area who was a former classroom teacher, principal, and college professor. He has worked with children and adults with disabilities all his life and hopes that this book brings an understanding to children with disabilities, their teachers, and their classmates. Dr. Bauer was born with a severe hearing impairment.

About the Author

Jim Luce writes children’s stories inspired by city life, community kindness, and the small moments that help children understand the world around them. A longtime advocate for education and inclusion, he believes stories can open doors to empathy and connection at any age. He lives in New York City, where many of his stories begin.

Final Reassurance

You both are not doing this to “be an author.”

We’re both doing this because the stories deserve to exist.

Everything else—Amazon listings, ISBNs, search results—is simply infrastructure.

When We’re ready, I can:

We’re building something quietly solid. That’s the best kind.

Purpose:

To establish Luce Publications as a credible, values-driven children’s and advocacy book imprint, beginning with a slate of meaningful narrative works that align with The Stewardship Report’s mission: empathy, community, inclusion, and shared human experience.

We should start by preparing three foundational titles for publication under the Luce Publications imprint:

A children’s story that centers on Down syndrome, empathy, and the beauty of difference — aligning directly with The Stewardship Report’s advocacy work.

A community-minded children’s picture book set on Roosevelt Island featuring twelve fluffy Shih Tzu puppies and everyday kindness — already drafted, illustrated, and ready with a defined visual style.

Bill’s deeply personal and powerful narrative about cancer and caregiving is both a Stewardship Report audience favorite and a book with potential reach among families, health-care professionals, and community groups. This piece is perfectly suited to anchor Luce Publications’ advocacy narrative line.

Together, these titles establish Luce Publications in three intersecting domains:

This diversity strengthens the imprint and broadens potential readership.

Platform: Amazon Kindle Direct Publishing

Publisher Name: Luce Publications

For each title, we recommend:

This approach keeps costs low and allows the books to be officially published, searchable, discoverable, and archived on Amazon and in bibliographic databases.

Each book should be published with strong category and keyword metadata that reflects both content and values.

Sample Categories

Sample Keywords

Good metadata ensures discoverability on Amazon, Google, and library systems.

Rather than a typical commercial launch with aggressive marketing and paid ads, we recommend:

This:

Over time, we can invite:

to share the books.

Once Mathew James, Shih Tzu, and Nana and Pap and a Thing Called Cancer are live:

By year’s end, Luce Publications has a tri-book catalog that:

Once the books are live and cataloged, we can:

This broadens the impact footprint without requiring retail bestseller status.

Publishing these books — even if sales are modest — achieves core goals:

This prioritizes impact over pressure, values over velocity.

Instead of one headline title, we anchor Luce Publications in a cohesive slate that:

Once live, these books become evergreen reference points for the values the Luce Foundation and Stewardship Report stand for.

Luce Publications now naturally divides into two complementary lanes:

These are:

They bring heart, setting, and literary tone.

This is the engine of the imprint.

Bill’s work forms a landmark inclusive children’s series—one that:

Importantly:

👉 This is not a random list.

It’s a taxonomy of childhood experience.

That’s powerful.

Your books and Bill’s series do not compete. They do different jobs:

| Your Books | Bill’s “And It’s Okay” Series |

| Narrative, story-driven | Conceptual, affirming |

| Place & character | Condition & identity |

| One-off titles | Structured series |

| Emotional immersion | Emotional reassurance |

Together, they say:

Children’s lives are complex—and every story deserves dignity.

That’s a publishing philosophy, not just a catalog.

A children’s book series that helps kids understand health conditions, disabilities, family circumstances, and identities—with reassurance, clarity, and compassion.

Each book:

This framing works for:

You do not publish all of these at once.

These establish:

Select 3–4 high-need, high-recognition topics, e.g.:

Later, carefully:

These require extra editorial care—but they’re incredibly important.

Here’s an updated imprint statement that quietly makes room for both your work and Bill’s series:

Luce Publications is an independent publishing imprint dedicated to stories that foster empathy, inclusion, and understanding. We publish children’s and narrative works that reflect real lives, real challenges, and the diverse experiences of families and communities. Our catalog includes both story-driven picture books and thoughtfully developed series that help children navigate health conditions, disabilities, identity, and change with reassurance and compassion. Through accessible, humane storytelling, Luce Publications seeks to affirm that every child’s experience matters—and that it’s okay to talk about the things that make us different.

Taken together, We are building:

This is the kind of catalog that:

And it grows organically—one honest book at a time.

Bill’s series is substantial.

Jim’s role here is not to “keep up” with it—but to curate, support, and publish it responsibly.

We are doing exactly that.

If you’d like next, I can:

We’re not just publishing books anymore.

We’re building something that will help families.

Jim Luce’s comprehensive coverage of Latin America focuses on the region’s most significant political and economic players, centering on the traditional “ABC Powers”—Argentina, Brazil, and Chile—while extending his analysis to include the smaller but strategically important nations of Paraguay, Uruguay, and Bolivia.

The ABC designation, historically used to describe South America’s three most powerful and influential countries, reflects a geopolitical reality that has shaped regional dynamics since the early 20th century. These nations have long served as the continent’s economic engines and political leaders, working together to address regional challenges while competing for influence across Latin America.

Luce’s reporting captures the contemporary evolution of these powers, from Argentina’s ongoing political controversies and economic challenges to Chile’s dynamic political transformation under millennial leadership. His analysis extends beyond the traditional triumvirate to examine how smaller nations like Paraguay, Uruguay, and Bolivia contribute to the complex tapestry of South American politics and regional integration.

“Human kindness has never weakened the stamina or softened the fiber of a free people. A nation does not have to be cruel in order to be tough. The vigorous expression of our American community spirit is truly important. The ancient injunction to love thy neighbor as thyself is still the force that animates our faith—a faith that we are determined shall live and conquer in a world poisoned by hatred and ravaged by war.” – Franklin D. Roosevelt, October 13, 1940

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (June 23, 2015)

[draft]

Emerging #Choreographer’s #DanceSeries: #MareNostrum Elements & #LPAC. #RohanBhargava #Dance

http://stewardshipreport.com/emerging-choreographers-series-mare-nostrum-elements-lpac-present-rohan-bhargava-marissa-brown-and-more/

[draft]

Emerging Choreographers Series (June 20, 2015)