Wall Street financier’s television appearance launched nationwide movement exposing religious abuse and financial exploitation schemes

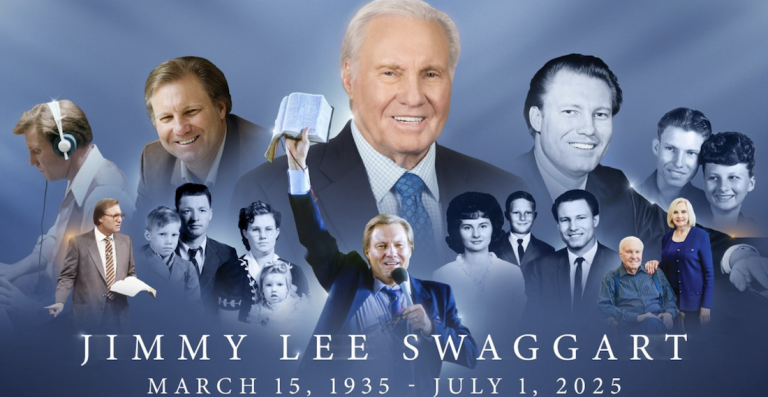

New York, N.Y. — In the spring of 1985, Jimmy Swaggart stood at the pinnacle of American evangelism. His fiery sermons reached millions of viewers across the United States and more than 100 countries worldwide. His ministry generated an estimated $140 million annually, making him one of the most powerful religious figures of the decade. Politicians courted his favor, followers sent him their last dollars, and his influence seemed unshakeable.

But in a Manhattan television studio that same year, a 26-year-old Wall Street banker named Jim Luce was about to light the fuse on a movement that would help expose the dark underbelly of televangelism and contribute to the eventual downfall of some of its most prominent figures.

The Donahue Moment

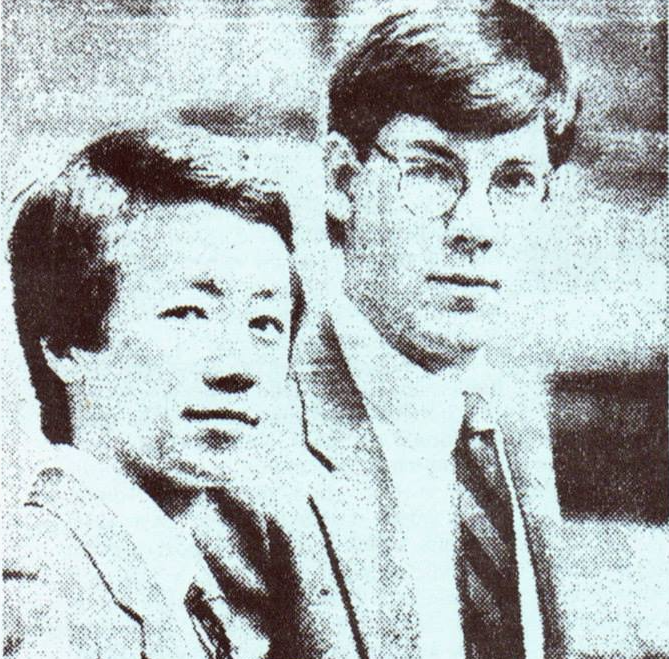

It began with a simple television appearance. On the Phil Donahue Show—the Oprah of its day—Luce and his co-founder Richard Yao introduced America to a revolutionary concept: “religious addiction.” For the first time on national television, they articulated what thousands of Americans had been feeling but couldn’t name—that the authoritarian demands of fundamentalist religion, particularly as practiced by powerful TV evangelists, could be psychologically damaging.

“The response was so overwhelming,” Luce recalls, “with 17,000 people

asking for help, that I had to choose between responding to those I

had said, ‘If you’re hurting, call us!’ and my Japanese banking career.”

The choice was stark but clear. Luce left his lucrative position as an assistant Eurobond portfolio manager with Daiwa Bank to dedicate himself full-time to what would become Fundamentalists Anonymous—a support network for people recovering from what they called “religious addiction.”

The Stories Pour In

The calls and letters that flooded in told a consistent story of abuse, manipulation, and financial exploitation. One woman, unable to afford basic necessities, was convinced it was “God’s Will” that she continue sending money to TV evangelists. Others reported emotional, sexual, and physical abuse justified by religious doctrine. In one extreme case, a caller reported that her husband had chained her in a basement for three months, attempting to “get the devil out of her.”

These weren’t isolated incidents. By 1987, Fundamentalists Anonymous had grown to 30,000 members across 41 chapters nationwide, with a budget reaching $300,000. The organization’s rapid growth was fueled by a simple but powerful message: “If the fundamentalist experience is working for you, fine, but we’re here if it isn’t.”

Taking on the Televangelists

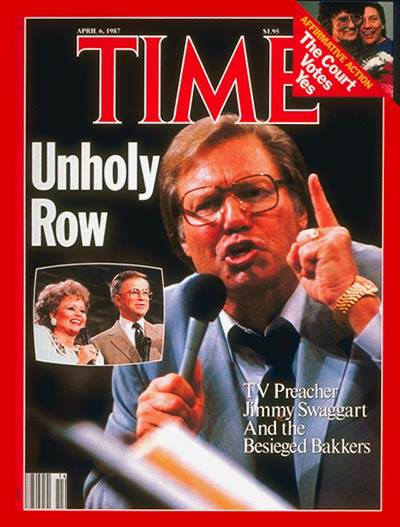

Luce didn’t limit his criticism to abstract theology. He targeted the titans of televangelism directly, including Jimmy Swaggart, Jerry Falwell, and Pat Robertson. His timing proved prescient. In 1987, the PTL scandal erupted, revealing Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker’s financial improprieties and sexual misconduct.

The following year, Jimmy Swaggart himself would be exposed in a prostitution scandal that would lead to his tearful, now-iconic television confession.

“I have sinned against you,” Swaggart told his congregation in that memorable 1988 sermon, tears streaming down his face. “I beg you to forgive me.” But for Luce, the confession was too little, too late. The damage had been done to countless followers who had trusted these figures with their faith and their finances.

The Science of Religious Addiction

What set Luce’s crusade apart from simple criticism was his insistence on treating religious addiction as a legitimate psychological phenomenon. After his Donahue appearance, dozens of therapists—psychologists and psychiatrists—reached out, revealing they were already treating patients for trauma related to authoritarian religious experiences.

Luce coordinated with these mental health professionals to organize the first-ever panel on religious addiction at the American Psychological Association’s 1987 annual convention in New York. The resulting research, published in the Journal of Religion and Health, marked cutting-edge work in understanding how “authoritarian religion” could cause or exacerbate mental health problems.

As renowned psychiatrist M. Scott Peck wrote in his endorsement of the organization: “Fundamentalism, with its pervasive sense of guilt about most normal physical and emotional feelings, and its patriarchal structure wherein the father’s word is law, creates family atmospheres where emotional, physical and/or sexual abuse of children is the rule, not the exception.”

Media Attention and Political Pushback

The mainstream media, fearful of the growing power of the Religious Right, embraced Luce’s message.

Major outlets including The New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Newsweek, and USA Today covered the organization’s work extensively.

The attention wasn’t limited to domestic press—even the London Observer and Toronto Star reported on the movement.

This media coverage infuriated the very targets of Luce’s criticism.Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority, with its millions of members, began attacking Fundamentalists Anonymous alongside the ACLU and Norman Lear‘s People for the American Way in direct mail campaigns.

For Luce, Falwell’s attacks served as validation:

“If the fundamentalist experience is working for you, fine, but we’re here if it isn’t.”

Congressional Testimony and Legal Action

The movement’s influence grew beyond support groups and media coverage. In 1988, Luce and Yao testified before Congress against the TV evangelists, bringing their message to the halls of power. They also formed a legal task force with three major goals: ensuring accountability of religious leaders to their followers, deterring future acts of abuse or misconduct, and protecting the legal rights of what they called “religious consumers.”

The timing was perfect. As the PTL scandal unfolded and other televangelist scandals emerged, Luce’s organization provided both a framework for understanding the abuse and a support system for victims. The organization operated from what The New York Times described as “an unfinished church basement in Manhattan,” keeping their exact location secret due to threats from angry fundamentalists.

Beyond Christianity

Luce’s critique extended beyond Christian fundamentalism. He understood that what he called “the Fundamentalist Mindset“—characterized by black-and-white thinking and authoritarian control—could infect any religious tradition. When author Salman Rushdie faced death threats over his novel The Satanic Verses, Luce called him “spineless” for agreeing not to publish the paperback edition.

“This spineless and shameless capitulation is a serious setback for free speech,” Luce told the Los Angeles Times in 1991. “It will only encourage more fundamentalist attempts, whether Christian or Islamic, to censor literature and art.”

Young Banker Sparks Crusade Against Televangelist Empire (Aug. 23, 2025)

75-word summary

Wall Street banker Jim Luce left his lucrative career in 1985 to battle televangelist abuse after appearing on Phil Donahue’s show. His organization, Fundamentalists Anonymous, grew to 30,000 members nationwide, providing support for victims of religious exploitation. Luce’s crusade helped expose scandals involving Jimmy Swaggart and the Bakkers, contributing to greater scrutiny of religious leaders and improved understanding of religious trauma in American society.