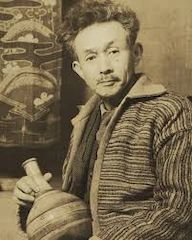

Yanagi Sōetsu (柳 宗悦)(1889-1961, age 72). The Japanese philosopher, art critic, and founding figure of the Mingei (民藝) movement, which championed the intrinsic beauty of utilitarian objects crafted by anonymous artisans [Luce Index™ score: 87].

Born in Tokyo during Japan’s rapid industrialization, Yanagi initially engaged with Western art through the Shirakaba (White Birch) literary journal, which he co-founded in 1910 to introduce figures like Rodin and Van Gogh to Japan.

His perspective shifted dramatically after encountering Korean Yi Dynasty ceramics in 1916, which revealed the aesthetic and spiritual depth of “humble” crafts vanishing under colonial modernization.

Collaborating with potters Hamada Shōji and Kawai Kanjirō, he coined the term Mingei—a portmanteau of minshū (common people) and kōgei (craft)—in 1925. Yanagi’s 1936 establishment of the Japan Folk Crafts Museum (Nihon Mingeikan) in Tokyo provided a manifesto in object form, housing over 17,000 pieces that embodied his ideals: functionality, regional identity, natural materials, and “the beauty of use” (yō no bi).

Core Philosophy and Principles

Yanagi’s Mingei theory rejected elitist bijutsu (fine art), arguing that true beauty emerged from collective tradition rather than individual genius. He outlined eight criteria for Mingei:

- Anonymity: Objects made by unknown craftspeople, free from ego.

- Functionality: Designed for daily use (e.g., Onta ware pottery, Kurume kasuri textiles).

- Locality: Reflecting regional materials and techniques, as seen in Okinawan bashōfu cloth or Ainu woodwork.

- Handcrafted Simplicity: Embracing “accidental beauty” like irregular glazes or uneven weaving.

- Affordability: Accessible to ordinary people, not luxury items.

Central to his aesthetic was chokkan (直観, direct perception)—an intuitive grasp of beauty beyond intellectual analysis—and tariki (他力, “other-power”), where artisans surrendered to natural materials and inherited forms, akin to Buddhist self-effacement. This spirituality linked Mingei to Zen and Shinto, evident in Yanagi’s admiration for worn, weathered objects that embodied wabi-sabi.

Collaborators and Institutional Legacy

- Hamada Shōji (1894–1978): Pioneering potter who established Mashiko ware; refused the “Living National Treasure” title to honor Mingei’s communal ethos.

- Kawai Kanjirō (1890–1966): Ceramicist known for natural glazes; likewise rejected state honors.

- Bernard Leach (1887–1979): British potter who disseminated Mingei ideals globally via A Potter’s Book (1940).

The Japan Folk Crafts Museum became the movement’s nexus, curating objects like Jōmon-era baskets, Edo-period jizaikake (adjustable hearth hooks), and Korean ŏhaedo folk paintings. Yanagi’s magazines Kōgei (1931) and Mingei (1939) further codified theories, influencing postwar design icons like his son Sori Yanagi, whose Butterfly Stool (1954) fused Mingei simplicity with industrial production.

Postwar Impact and Critiques

Post-1945, Mingei faced paradoxes:

- A 1960s “Mingei boom” commodified folk crafts, contradicting Yanagi’s anti-commercial ideals.

- Industrialization nearly erased traditions Yanagi sought to preserve, prompting urgent documentation of regional workshops.

- Scholars like Yuko Kikuchi noted Mingei’s role in cultural nationalism, though Yanagi himself opposed Japanese militarism.

Global Resonance

Yanagi’s The Unknown Craftsman (1972) became a worldwide touchstone. Contemporary applications include:

- Theaster Gates: Chicago artist’s “Afro-Mingei” project, revitalizing Black vernacular craft.

- Islamic craft revival: Proposals to apply Mingei principles to preserve Hama (Syria) textiles and Ottoman futuwwa guild traditions.

- Sustainability movements: Mingei’s emphasis on handwork and ecology aligns with modern “slow design.”

Yanagi died in 1961, but his vision endures in Japan’s 200+ mingei-inspired galleries and UNESCO’s recognition of traditions like Ryukyu bashōfu weaving.