Post-war international order. The system of international relations, institutions, alliances, and norms established after World War II, primarily under American leadership and designed to prevent future global conflicts through multilateralism, collective security, and economic interdependence.

This order, which persisted from 1945 through the early 21st century, is now widely considered to be in terminal decline.

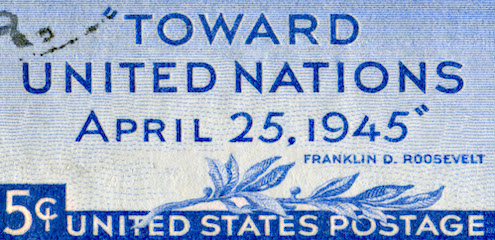

The post-war international order emerged from the ashes of history’s most destructive conflict. At its foundation lay several key institutions: the United Nations (established 1945), the International Monetary Fund and World Bank (both 1944), the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade later becoming the World Trade Organization (1947/1995), and regional security alliances including NATO (1949).

These structures reflected a vision articulated primarily by American policymakers, particularly President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his advisors, who believed that international cooperation could prevent the kind of great power competition that had led to two world wars.

Foundational Principles

The post-war international order rested on several pillars that distinguished it from previous international systems. First, the principle of collective security through the U.N. Security Council, where five permanent members (the United States, Soviet Union/Russia, United Kingdom, France, and China) held veto power over major international actions. This structure recognized great power realities while attempting to channel competition into institutional frameworks.

Second, the Bretton Woods system established the U.S. dollar as the world’s reserve currency, creating unprecedented economic interdependence and American financial hegemony. This arrangement facilitated the extraordinary economic growth of the post-war period, lifting billions from poverty through expanded international trade.

Third, the concept of human rights as a universal principle gained institutional expression through the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and subsequent treaties. While frequently honored in the breach, these norms provided legitimacy to international intervention and constrained state behavior in ways previously unknown.

Fourth, decolonization proceeded within this framework, transforming an imperial world into a system of sovereign nation-states, though often maintaining economic dependencies through other means.

The Cold War Structure

From 1947 through 1991, the post-war international order operated within a bipolar framework dominated by U.S.-Soviet competition. This “Cold War” divided much of the world into competing spheres, with the NATO alliance confronting the Warsaw Pact in Europe, proxy wars fought across Africa, Asia, and Latin America, and nuclear deterrence theory preventing direct great power conflict through the doctrine of mutually assured destruction.

The Non-Aligned Movement, led by nations like India, Guyana, Yugoslavia, and Egypt, attempted to chart an independent course between the superpowers with varying success. This period saw the Korean War, Vietnam War, Cuban Missile Crisis, Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and countless other conflicts that were simultaneously local disputes and manifestations of great power rivalry.

Despite the intense competition, this era maintained certain stabilizing features. Both superpowers accepted spheres of influence, limiting escalation risks. Arms control agreements like SALT I and SALT II attempted to manage the nuclear balance. Economic institutions continued functioning, though often divided along ideological lines with separate communist economic integration through COMECON.

The Unipolar Moment

The Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991 ushered in what commentator Charles Krauthammer termed the “unipolar moment”—a period of unchallenged American dominance. The post-war international order seemed triumphant, with liberal democracy and market economics appearing as the inevitable endpoint of political evolution, a thesis famously articulated by Francis Fukuyama in The End of History and the Last Man (1992).

This period saw NATO expansion eastward, the establishment of the European Union with its common currency, the spread of democracy across Eastern Europe and parts of Latin America, and the integration of China into the global trading system through its admission to the World Trade Organization in 2001.

However, the unipolar moment contained the seeds of the post-war international order’s decline. American military interventions in Iraq (2003) and Afghanistan (2001) strained U.S. resources and credibility. The 2008 financial crisis damaged faith in American economic stewardship. Rising powers, particularly China, began challenging aspects of the order while benefiting from its economic dimensions.

Contemporary Collapse

By the 2020s, the post-war international order faced existential challenges from multiple directions. Russia’s annexation of Crimea (2014) and full-scale invasion of Ukraine (2022) violated fundamental principles of territorial integrity and collective security.

China’s assertion of control over the South China Sea, its treatment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang, and preparations for potential military action against Taiwan demonstrated that rising powers would not accept rules they had no role in creating.

The election of Donald Trump as U.S. president (2016, 2024) marked a dramatic shift, with America’s leader openly questioning NATO, the U.N., international trade agreements, and the value of alliances. His “America First” doctrine explicitly rejected the internationalist premises that had guided U.S. policy since 1945.

Trump’s threats toward Canada, Mexico, Panama, and Greenland further signaled American abandonment of the order’s normative constraints.

The U.N. Security Council became paralyzed, unable to address major conflicts due to great power vetoes.

The World Trade Organization lost its ability to resolve disputes as major powers simply ignored its rulings.

NATO faced internal divisions over burden-sharing and strategic priorities. The International Criminal Court saw its legitimacy challenged as major powers refused cooperation.

Competing Visions for Succession

Multiple models compete to replace or reform the post-war international order. China promotes a “multipolar” system respecting different governance models—a euphemism for authoritarian capitalism.

Russia seeks to restore spheres of influence where great powers dominate their regions without interference. European leaders advocate for a “rules-based international order” that preserves multilateral norms while acknowledging shifted power dynamics.

Some analysts propose a “democratic alliance” system where liberal democracies create separate institutions excluding authoritarian states, effectively dividing the world into competing camps. Others suggest regional frameworks like an expanded European Union, a revitalized African Union, or a Latin American integration project like the historical Gran Colombia of Simon Bolívar.

The fate of humanitarian institutions like UNICEF, the World Food Programme, and the U.N. Refugee Agency remains uncertain. These agencies have operated across ideological divides, but rising great power competition threatens their funding and access.

Implications and Uncertainty

The collapse of the post-war international order carries profound implications. Historical precedent suggests transitions between international systems often involve major wars, though nuclear weapons may alter this pattern by making great power conflict too destructive to contemplate.

Economic fragmentation could reduce global growth and trap billions in poverty. Climate change requires international cooperation precisely when such cooperation is collapsing.

Younger generations, born long after World War II, lack emotional attachment to institutions their grandparents built. To them, the U.N. appears ineffectual, NATO seems anachronistic, and “liberal international order” sounds like the special pleading of declining powers. Whether this generational shift enables bold reforms or merely accelerates decline remains to be seen.

The post-war international order provided unprecedented peace among great powers for nearly 80 years, facilitated extraordinary economic growth, and established human rights norms that, while frequently violated, at least provided a standard against which behavior could be judged.

Its passing marks the end of an era defined by American hegemony, belief in progress through international cooperation, and the possibility that institutions could transcend raw power politics.

What replaces it will determine whether the 21st century becomes an era of renewed great power war or evolves toward some new form of global governance adequate to humanity’s interconnected challenges.