The ICC was founded to prosecute individuals for war crimes, genocide, and crimes against humanity when national courts fail to act

The Hague — A complex relationship exists between countries that opt out of the International Criminal Court (ICC) and authoritarian governance, though the correlation is far from straightforward.

Established in 1998 under the Rome Statute, the ICC aims to prosecute individuals for war crimes, genocide, and crimes against humanity when national courts fail to act.

While over 120 nations support this mission, prominent absentees like the United States, Russia, China, Israel, Libya, and Qatar raise questions about the interplay between sovereignty, accountability, and political control.

In March 2025, former Philippines president Rodrigo Duterte appeared via video link at his first hearing at the International Criminal Court, citing health reasons.

Many non-members cite sovereignty as a primary reason for avoiding ICC jurisdiction.

- China, meanwhile, objects to the ICC’s ability to override national judicial decisions, viewing it as a threat to its autonomy and influence over allies like Syria.

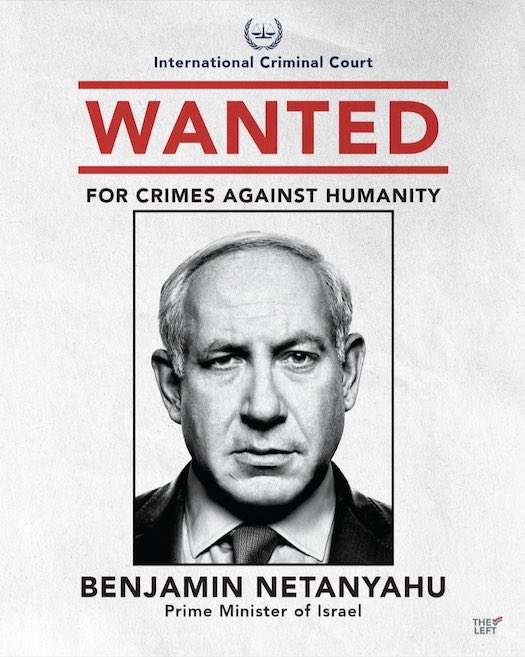

- Hungary announced this month its intent to withdraw from the ICC, hours after Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, subject to an ICC arrest warrant, visited the country. If completed, this withdrawal would take effect one year from the formal notification, potentially in April 2026, making Hungary a non-member thereafter. Until then, it remains a member.

- Iran signed the accord originally but has not ratified it yet and remains non-committal.

- Israel signed in 2000 but left two years later after the ICC concluded transferring populations into occupied territory was a “war crime.”

- Myanmar is not a member, although the ICC has claimed jurisdiction over crimes like the deportation of Rohingya.

- North Korea is a non-signatory with no engagement with the ICC, often criticized for human rights abuses but outside the court’s reach absent a U.N. Security Council referral.

- Philippines joined in 2011 but withdrew in 2019 under President Rodrigo Duterte following ICC scrutiny of his administration’s brutal “war on drugs.”

- Russia initially engaged with the court but President Vladimir Putin had it withdraw in 2016 after the ICC labeled its conflict with Ukraine an international armed conflict, prompting Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov to call the court “one-sided and inefficient.”

- U.S.A. signed the Rome Statute under President Bill Clinton but withdrew under George W. Bush, fearing prosecution of American soldiers for actions abroad. The 2002 American Service Members’ Protection Act underscored this stance, rejecting ICC authority over U.S. personnel.

China, Iran, Israel, North Korea, Philippines, Russia, United States

Rodrigo Duterte, Ali Khamenei, Kim Jong Un, Benjamin Netanyahu, Vladimir Putin, Donald Trump, Xi Jinping

Sadly, some weak countries has never signed or withdrawn, mostly because they feel their small governments cannot withstand the pressure of international justice. These include Haiti, Morocco, Nepal, and Thailand. These cases highlight a common thread among non-members: a preference to shield national policies or military actions from external judgment, often linked to turbulent domestic or geopolitical contexts.

Yet, the assumption that only democracies embrace the ICC while autocracies shun it oversimplifies the picture.

Some authoritarian regimes strategically join the ICC to bolster their own power.

In a study, “The Politics of Punishment: Why Dictators Join the International Criminal Court,” argues that dictators facing high domestic political competition are more likely to ratify the Rome Statute.

By doing so, they can refer cases to the ICC to target political rivals, leveraging the court’s authority to weaken opposition without risking their own accountability.

Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni exemplifies this tactic.

In 2004, he invited the ICC to investigate the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), a rebel group threatening his regime. The resulting arrest warrants targeted LRA leaders, leaving government forces unscrutinized despite their own alleged abuses.

Statistical evidence supports this pattern: dictatorships with greater political competition are more likely to join the ICC, subsequently reducing violence and enhancing leader survival by neutralizing threats.

Geopolitical and domestic factors further complicate the ICC’s role.

China’s reluctance stems not from fear of prosecution but from its alliances, such as with former strongman Bashar al-Assad of Syria, accused of war crimes. Joining the ICC would obligate China to cooperate in investigations against such allies, clashing with its economic and strategic interests.

Qatar, a wealthy autocracy, maintains pragmatic neutrality in conflicts like Gaza, avoiding ICC membership to preserve flexibility in its foreign relations, including ties with groups like Hamas.

The data paints a nuanced picture.

Of the ICC’s 37 arrest warrants issued by 2021, only one from a self-referred case—a dictatorship—targeted a government supporter, suggesting autocrats can manipulate the court’s focus.

Conversely, non-members like the U.S. and Russia face no such constraints, pursuing unilateral policies without ICC oversight. Yet, democratic non-members like the U.S. also resist, driven by concerns over sovereignty rather than authoritarianism.

This duality challenges the narrative of a clear divide.

While authoritarian regimes often avoid the ICC to evade accountability, some embrace it as a tool for control. Membership, then, does not inherently signal democratic intent, nor does absence confirm tyranny.

The ICC’s asymmetric costs—higher for opponents than rulers in dictatorships—shape these decisions, reflecting a blend of self-interest and strategic calculation.

While a pattern links some authoritarian governments to ICC non-membership, the relationship is intricate. Sovereignty concerns and geopolitical strategies drive avoidance, yet domestic power dynamics can spur participation. The ICC’s role in global justice remains a contested space, shaped as much by politics as by principle.

Why Dictators Hate (or Love) the International Criminal Court (April 4, 2025)