A witness recalls the vibrant intersection of art, activism, and romance in 1980s New York

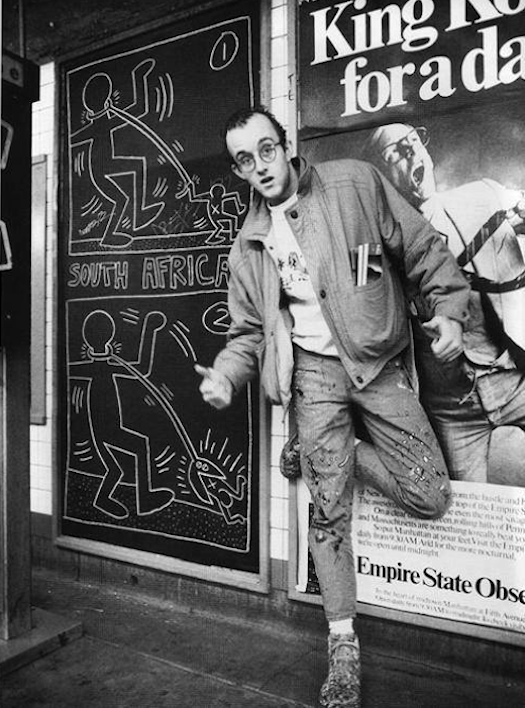

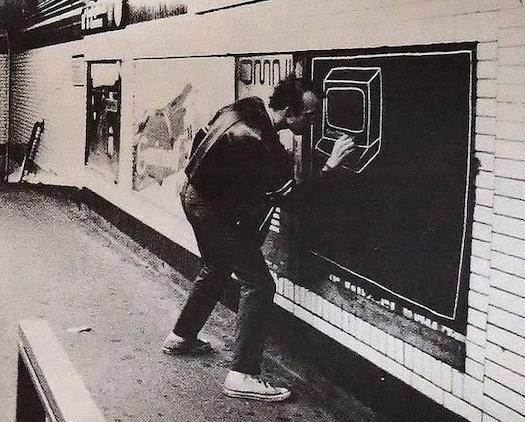

New York, N.Y. – The black paper covering expired advertisements in the subway tunnels became Keith Haring’s canvas, transforming the underground arteries of New York City into galleries of hope and defiance.

In 1984, these ephemeral chalk drawings were more than artistic expressions—they were declarations of identity in a city where art, politics, and personal liberation collided daily.

The Underground Canvas Revolution

Walking through Astor Place station in 1984, commuters would encounter Haring’s distinctive radiant babies, barking dogs, and dancing figures emerging from the darkness.

These weren’t sanctioned murals but spontaneous acts of creative rebellion.

The young artist from Pennsylvania had found his voice in the subway system, creating what he called “subway drawings”—works that would reach millions of New Yorkers before being inevitably covered by new advertisements.

The frequency of these appearances revealed Haring’s prolific nature and his commitment to making art accessible.

Unlike gallery pieces that required entrance fees and cultural capital, his subway works democratized art, bringing it directly to working-class commuters, students, and tourists navigating the city’s underground maze.

Factory Nights and Artistic Encounters

The East Village in the mid-1980s pulsed with creative energy, and The Factory served as a gravitational center for artists, musicians, and cultural figures. Attending a gathering there in spring 1984 with partner Richard Yao and Hong Kong designer Jonny Fu offered a glimpse into this rarefied world where art and celebrity intersected.

Andy Warhol’s presence at these gatherings was notable for its understated quality. The artist who had revolutionized pop art appeared almost mundane in person—a reminder that transformative cultural figures often possess quiet, observational natures that belie their public impact.

His tendency to appear briefly before retreating to private spaces suggested someone who preferred watching to performing, despite being at the center of New York’s art world.

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s presence added another layer to these gatherings. The young artist’s reputation for intensity and artistic brilliance preceded him, creating an aura that could be both magnetic and intimidating.

His work was already challenging conventional boundaries between high and low culture, street art and gallery art, much like Haring’s subway interventions.

Love in the Time of AIDS

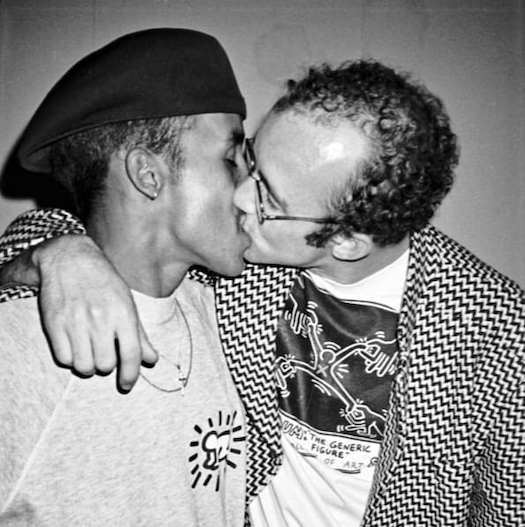

The 1986 photograph of Keith Haring and Juan Rivera by Andy Warhol captures more than a romantic moment—it documents a relationship that embodied the complex intersection of love, art, and activism during the AIDS crisis.

Their connection, though brief and complicated, represented the broader struggle of L.G.B.T.Q. individuals navigating identity and relationships during a period of unprecedented health crisis and social stigma.

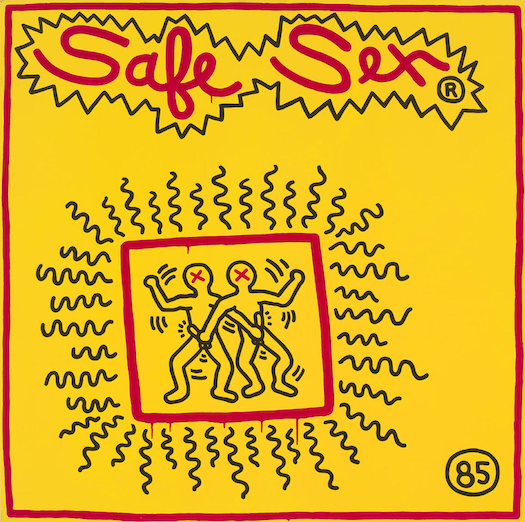

Haring’s relationship with Rivera informed his increasingly political artwork. As the AIDS epidemic devastated the gay community, Haring transformed his accessible visual language into a tool for advocacy.

His later works directly addressed safer sex, H.I.V. prevention, and the urgent need for medical research and social support.

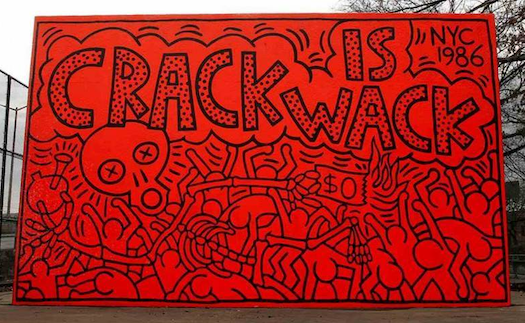

Art as Activism

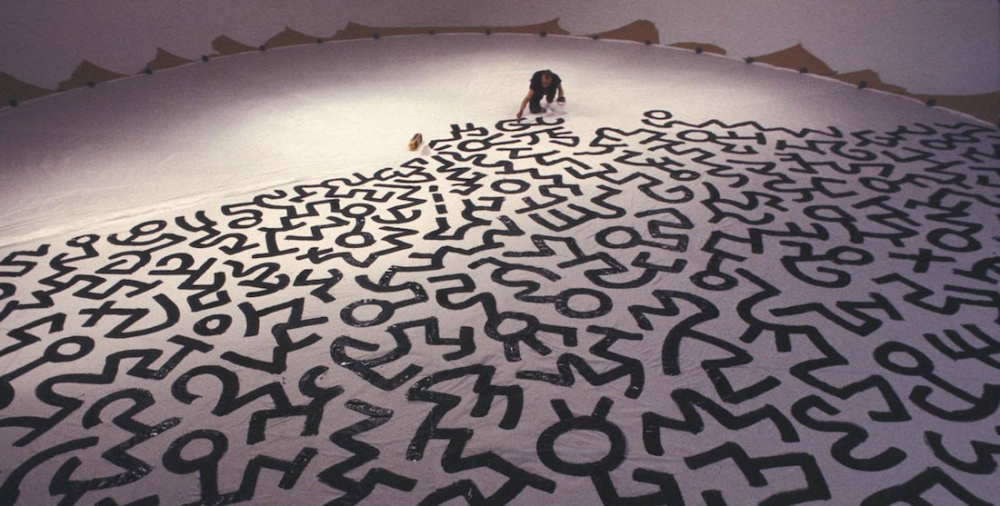

The personal became political in Haring’s work as he witnessed friends and lovers succumb to AIDS-related complications.

His art evolved from joyful celebration to urgent messaging, maintaining its accessibility while addressing life-and-death issues.

The same radiant babies that once simply celebrated life now appeared in contexts warning about unprotected sex and promoting H.I.V. awareness.

This transformation reflected a broader shift in 1980s art, where creators increasingly understood their work as platforms for social change.

Haring’s subway drawings had always been political in their democratic accessibility, but his later pieces became explicitly activist, using his established visual vocabulary to save lives.

Legacy of Love and Loss

Haring’s death from AIDS-related complications in 1990 at age 31 marked the end of a brief but transformative career.

Rivera’s death a few years later in Spanish Harlem represented another casualty of the epidemic that claimed countless lives, particularly among marginalized communities.

Their story reflects the broader tragedy of an entire generation of artists, activists, and lovers lost to a disease that the government initially ignored.

Yet Haring’s legacy extends beyond tragedy. His work demonstrated how art could serve simultaneously as personal expression, political statement, and public service.

The subway drawings that once decorated Astor Place station walls continue to influence contemporary artists who seek to make their work accessible and socially relevant.

The 1984 encounters with Haring, Warhol, and Basquiat in East Village venues now seem like glimpses of a cultural moment that was both ending and beginning.

These artists were creating new forms of expression while facing unprecedented challenges, their work serving as both documentation and resistance.

Summary

In 1984 New York, Keith Haring transformed subway stations into galleries while navigating love and activism. His relationship with Juan Rivera, captured in an Andy Warhol photograph, reflected the intersection of personal and political during the AIDS crisis. Both artists died young, leaving behind revolutionary art that challenged boundaries between high culture and street expression.

When Art Met Love: Keith Haring’s Personal Revolution (July 14, 2025)

#KeithHaring #AndyWarhol #EastVillage #SubwayArt #1980sNewYork

#AIDSActivism #JuanRivera #ArtHistory #LGBTQ #BasquiatEra

TAGS: Keith Haring, Juan Rivera, Andy Warhol, subway art, East Village, 1980s New York, AIDS activism,

Jean-Michel Basquiat, LGBTQ history, pop art, street art, The Factory, Astor Place, art and politics