As great powers pursue competing philosophies of peace through dominance, the global body designed to prevent conflict becomes theater of dysfunction

By Jim Luce, Editor-in-Chief

New York, N.Y. — The chamber was familiar to all of them—the horseshoe table, the flags, the translation booths where patient linguists converted diplomatic language into something approximating clarity. But the atmosphere had changed in recent months, grown heavier with a recognition that few wanted to acknowledge aloud.

The Chinese ambassador arrived first, as he often did, reviewing briefing materials that outlined his government’s position with characteristic precision. China believed its rising influence represented not aggression but restoration—the natural order reasserting itself after what they viewed as a brief, anomalous period of Western dominance. Their vision of peace required the world to accept this shift gracefully.

The Russian Ambassador entered next, nodding curtly to his counterpart before taking Russia’s seat. They’d worked together often enough in recent years to develop an understanding, if not exactly trust. Both knew what was coming.

When the U.S. Ambassador finally arrived, she carried herself with visible exhaustion. The new instructions from Washington had been clear: minimal engagement, no new funding commitments, and certainly no support for what her president had called “expensive talk shops that accomplish nothing.”

Her government now believed peace came through American strength, through deals made bilaterally with leverage, not through what they saw as endless multilateral negotiations that constrained American power.

The British and French ambassadors exchanged glances. The ten non-permanent members shifted in their seats.

The Theater of Deadlock

“We all know where this is going,” the Russian said quietly, before the session officially began. “Another veto. Another deadlock. Another month of people dying while we perform this theater.”

The Chinese ambassador said nothing, but his silence was agreement enough.

America’s ambassador looked at them both. “My government believes strength brings peace. Clear deterrence. Decisive action. Not… this.” She gestured at the chamber.

“Your government’s strength?” the Chinese ambassador asked mildly. “Or ours?”

It was the question that hung over everything now. Three great powers, each believing that their strength would bring peace, each viewing the others’ strength as threat. Russia saw its assertiveness as restoring rightful security interests. China viewed its growing influence as the natural order being restored. America believed its military and economic dominance was the guarantor of stability.

But strength without agreement was just competing force. And the Security Council—designed to channel power into consensus—had become the place where three visions of peace-through-strength canceled each other out.

The Paradox of Indispensable Dysfunction

The Security Council is broken, yet it remains the only global institution with the authority to authorize collective security action.

It’s simultaneously indispensable and dysfunctional. The U.S. withdrawal of

support weakens it further, based on a philosophy that American strength alone can

secure peace. But Russia and China hold the same belief about their own strength.

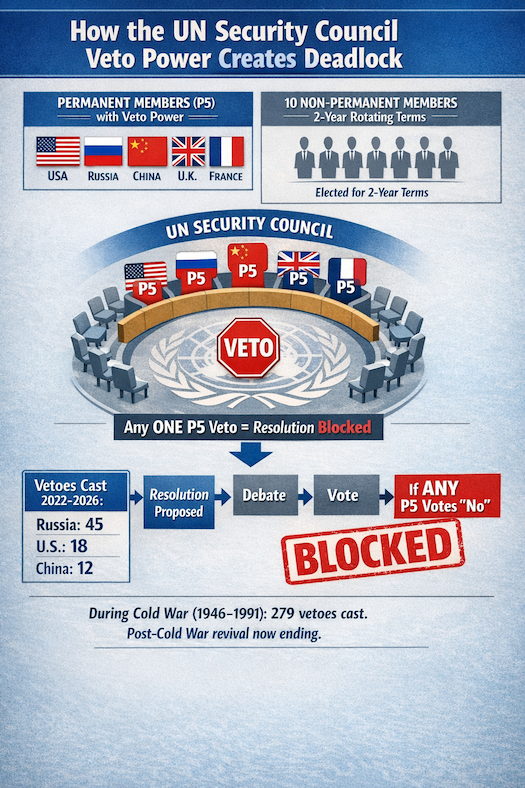

The chamber where these competing visions meet holds fifteen seats around that famous horseshoe table. Five permanent members—the U.S., Russia, China, the United Kingdom, and France—each wield veto power, a recognition of geopolitical reality from 1945 that has become a straitjacket in 2026. Ten non-permanent members rotate through two-year terms, their votes often symbolic exercises in a body where real power rests with the five.

On paper, the system was designed to prevent global conflict by requiring the great powers to agree before the United Nations acted with force. In practice, that same requirement now prevents the U.N. from acting at all when the great powers themselves are in conflict—or when their proxies are.

Ukraine remains a frozen crisis, with Russian vetoes blocking any meaningful action. Gaza sees American vetoes protecting Israel from consequences. Taiwan looms as the ultimate test case, where Chinese interests would trigger an automatic veto of any intervention. Each permanent member uses its veto to protect its sphere of influence, its allies, its vision of how the world should work.

Where Agreement Still Exists

Yet history and human nature suggest pathways forward, even through this darkness. The work begins not where agreement is impossible, but where it still exists.

The Security Council deadlocks on Ukraine, Gaza, Taiwan. But narrower issues—pandemic preparedness, counterterrorism, maritime security, climate-driven displacement—may offer ground where interests align enough to cooperate. Small successes can rebuild institutional muscle memory.

Norway, Singapore, South Africa, and Brazil have emerged as creative middle powers, facilitating dialogue and building coalitions around specific issues when the great powers deadlock. The U.N.’s dysfunction creates space for diplomacy elsewhere, in regional organizations and informal groupings where veto power doesn’t apply.

The Cold War’s most dangerous moments were resolved not by strength alone, but by strong powers choosing to talk. The Cuban Missile Crisis, arms control negotiations, the Helsinki Accords—each represented strength providing security to negotiate, and negotiation preventing strength from becoming catastrophe.

The Unglamorous Work Continues

While the Security Council deadlocks, U.N. peacekeepers still stand between hostile forces in a dozen conflicts. Humanitarian workers still deliver food to millions. Mediators still shuttle between parties. UNICEF still vaccinates children. The World Food Programme still feeds the hungry.

These efforts save lives even when they don’t make headlines, even when the great powers can’t agree on mandates or funding. The infrastructure of peace—international law, humanitarian norms, diplomatic channels—is weakened but not destroyed.

The U.N. seemed irrelevant during much of the Cold War, when veto deadlocks were constant. Yet it survived, adapted, and became more functional when circumstances changed. Institutions persist through dark periods, maintaining capacity and legitimacy until they’re needed again.

The 51% Solution

On a personal note, our charity was affiliated with the United Nations for a decade and I became very accustomed to its workings. An Undersecretary General even spoke at my surprise fiftieth birthday. I am not sure if that experience makes me more or less hopeful.

I think I am more hopeful because I believe humanity is 51% good and that one percent keeps our world in balance. If it is not taken for granted. It’s a thin margin, perhaps, but it’s held through previous crises.

Peace isn’t only built in security council chambers. It’s built in communities, in how we bridge divides locally, in whether we teach our children to see humanity in others, in whether we resist hatred in our own hearts and circles.

The hatred and division are real. But so is the fact that most people, everywhere, want safety and dignity for their families. The current system doesn’t work—but the question isn’t whether it’s broken. The question is what we do in the meantime.

Whether we give in to despair, or whether we work for peace in whatever capacity we have, however small that might feel. Whether we tend the institutions and norms and relationships that will be needed when, inevitably, circumstances change again.

In the chamber, the session began. The veto was cast. The deadlock held.

But in offices throughout the building, diplomats continued drafting resolutions, humanitarian workers continued planning relief operations, and translators continued their patient work of making different languages speak to one another.

The work continues, because it must. The 51% requires it.

5 Times the U.N. Security Council Actually Worked—and Why That Era Is Ending

For all its gridlock, the Security Council has occasionally done what it was designed to do. These moments now feel like relics.

1. Korea, 1950: The War That Slipped Through the Cracks

When North Korea invaded the South, the Soviet Union was boycotting the Council—and missed the vote. U.N. forces were authorized within days.

Why it worked: No veto, no blockage.

Why it wouldn’t today: Great powers never skip the room anymore.

2. Suez, 1956: When Rivals United Against Empire

The U.S. and Soviet Union shocked the world by jointly opposing Britain and France’s invasion of Egypt. Pressure from both sides forced a retreat.

Why it worked: Strategic interests briefly aligned.

Why it wouldn’t today: Alliances are rigid; surprises are rare.

3. Kuwait, 1991: Peak Post–Cold War Cooperation

After Iraq invaded Kuwait, the Security Council authorized force to restore sovereignty. It was multilateralism at its zenith.

Why it worked: Shared belief in a rules-based order.

Why it wouldn’t today: That belief has collapsed.

4. Libya, 2011: The Abstention That Changed Everything

Russia and China abstained—rather than vetoed—a no-fly zone to protect civilians. NATO intervention followed, then regime collapse.

Why it worked: Abstention allowed action.

Why it backfired: Moscow and Beijing felt deceived—and vowed “never again.”

5. Iran Deal, 2015: The Last Consensus

The Security Council unanimously endorsed the Iran nuclear agreement, lifting sanctions in exchange for oversight.

Why it worked: Diplomacy still mattered.

Why it feels ancient: Trust between powers has evaporated.

The Takeaway

The Security Council hasn’t changed—but the world around it has. Today’s great powers see unilateral strength, not collective decision-making, as the path to security. The veto was meant as a safeguard. It has become a weapon.

The result: a council that meets constantly—and decides almost nothing.

Three Visions of Strength Leave Security Council Paralyzed (Jan. 16, 2026)