In May 2013, the South Gallery of the Oglethorpe University Museum of Art was renamed The Shelley and Donald Rubin Gallery.

Donald and Shelley Rubin in Tibet, 2002. Photos courtesy of Donald Rubin and the Rubin Museum.

Both the island and the art are an unusual mix of the traditional and the modern, of the ordinary and the special, of simplicity and incredible complexity.

New York, N.Y. Donald and Shelley Rubin are Tibetan art in New York City. This point is difficult to argue with. They founded the Rubin Museum of Art (RMA), which opened its doors in October 2004 and is now recognized as the premier museum of Himalayan art in the West.

What is less known is that these two thought leaders and global citizens are also patrons of the contemporary Cuban art scene.

Chatting with Don Rubin [Luce Index™ rank: 100] last week, I admitted that I knew little about Cuban art. He challenged me to get my arms around it. Having been an Asian Studies major with a minor in art, I rose to his challenge.

Shelley and Donald Rubin started collecting Cuban art recently.

This fall, the Museum of Art of Don’s alma mater Oglethorpe University in Atlanta opened an exhibition featuring their collection. Don graduated from Oglethorpe in 1956 with a BA.

This show — “¿What is Cuban Art?” — marks the first public display of this group of works and the first American presentation of many of the works. The Rubins have acquired such widely varying pieces that a newcomer to the art of Cuba might well ask, What is Cuban art?

Over 60 works of art by over two dozen contemporary Cuban artists were selected by co-curators Sandra Levinson, from The Center for Cuban Studies in New York, and Rachel Weingeist from the collection of Shelley and Donald Rubin.

The artists work in Cuba, the U.S., and from around the world. All are living but for one who died only weeks ago in Cuba. Some artists represented — Manuel Mendive, Carlos Estévez, Elsa Mora, and Sandra Ceballos — have achieved international renown, whereas others are almost unknown outside of Cuba.

Zaida del Rio. Fe, Esparanza y Caridad, 2001. Watercolor. 30 x 40 inches.

The curators have invited artists, critics, curators, and collectors to weigh in on the question — “¿What is Cuban Art?” — and their wide-ranging answers are included in the show as intriguing wall texts.

This exhibit ranges from the most popular to the most intellectual tastes, and features work from artists who range from self-taught to highly-trained. The youngest artist, Mabel Poblet, is 23; the oldest, Richar Bruff Bruff, is in his 80’s.

Like most of the Americas, Cuba is a melting pot of immigrants. Over centuries it has grown with Spanish colonials, African slaves, and Chinese laborers.

A place of apparent poverty today, Cuba is also a country incalculably rich in history, politics, and the arts. Cubans experience food shortages and are poor in ways that are hard for U.S. citizens to grasp.

On the other hand, Cubans receive as their birthright much that we don’t but should have here in the U.S. — free health care and education and subsidized goods of all kinds. Cubans share as a community both the advantages and disadvantages of living on their troubled and troublesome island.

To explore these elements of the Cuban culture, Oglethorpe University will feature a lecture series during the run of the exhibit. The lectures will cover such topics as a history of contemporary art in Cuba to the rise of Cuban hip hop, and Cuban cinema.

Yamilys Brito. Obatalá, 2003. Tempera on paper. 20 x 14 inches (left, monochrome).

José García Montesbravo. Mi Amigo Sincero, 2003. Acrylic on canvas. 34 x 25 inches.

Yamilys Brito. Obatalá, 2003. Tempera on paper. 20 x 14 inches (left, monochrome).

José García Montesbravo. Mi Amigo Sincero, 2003. Acrylic on canvas. 34 x 25 inches.

This island has weathered an extended U.S. embargo which may soon be ended by a more intelligent president, and all of the internal economic and political problems that embargo — as well as Cuba’s own unique brand of socialism — engender.

Shelley and Donald Rubin are avid art collectors who purchased their first piece of traditional Tibetan art in the mid-1970s, beginning a decades-long commitment to the preservation of the art of the Himalayas.

As the Rubins passion and collection grew, so did their desire to inspire a similar passion in others.

To understand a specific cultural milieu of Cuban art, one needs to interview those most familiar with it.

The Cuban writer Alberto Barral began my introduction. “Cuban art today is a contemporary language with a salsa mix. It has much of the international language that speaks for a generation, but with a tropical vision all its own. It comes with all the complications and extensions that this inevitably means.”

“Besides the elegance, beauty and true artistry, Cuban art is a vehicle for Cuban artists to express their true communication and their feelings, perhaps creating a vehicle for furthering cultural exchange between the U.S. and Cuba,” explains Luly Duke, founder and president of Fundacion Amistad.

“Cuban art has a history of focusing on different things and I think it has matured as a form of social conscience, progressive and very positive. Cuba is an island with much history and has given birth to great talent. This phenomenon has grown more complex with time and what started with certain nationalistic and folkloric elements became later a philosophy and way of thinking that expresses itself in the art.” - Carlos Estevez, artist

In the words of Cuban artist Carlos Estevez, “Cuban art is what we Cubans make, no matter where we live. The fact that I was born and grew up in Cuba makes me see life and the world in a unique way. I can become part of a different society or culture very different from my own (and I think that enriches the artist’s imagination) but the essence, the axis, comes from our experience.”

“Cuban art has a history of focusing on different things and I think it has matured as a form of social conscience, progressive and very positive,” Carlos says. “Cuba is an island with much history and has given birth to great talent.”

“This phenomenon has grown more complex with time and what started with certain nationalistic and folkloric elements became later a philosophy and way of thinking that expresses itself in the art, Carlos adds.

Carlos Estévez. Mirar a Los Lejos, 1998. Watercolor and pencil on paper.

29 1/2 x 43 1/2 inches.

“Spirituality, politics, and innovation mold the very fabric of Cuban art. Beneath this surface are the complex and interwoven traditions of Africa and Spain, China and the United States,” writes art Historian and curator Gail Gelburd, Ph.D.

“The warp and weft become not a specific style, but rather a unique state of mind. The art becomes the visual equivalent of a hot night, sandy shores, crumbling buildings, vibrant sounds, and intellectual discourse,” Gail states.

One collector, Howard Faber, says that, “Collecting Cuban Contemporary art is the best kept secret by those in the know in the art market. This genre encompasses probably the finest examples of contemporary art created in the last forty years.”

Cuban art is a way to understand its people.

According to Alberto Magnan, it “brings you closer to the inner thoughts and meaning of the people of Cuba. It is pure art — done for the sake of art and not for the art market. It is art that excites and takes our minds to another level.”

According to another collector, Orlando Justo, “Cuban art is an enjoyable representation of Cuban roots and traditions of people’s questions and answers, happiness and worries, expressed with sharp humor, subtle irony and profound intellectual thinking. It is, in summary, a snapshot inside Cuban people’s minds and daily life.”

Abelardo Mena, a writer about the Cuban avant garde, says “Long live the anti-utopian, optimistic, and rebellious features of Cuban Art that will live forever young!”

Cuban art experts are quoted as part of the show:

“For me, Cuban art is the history of its people and culture layered with international techniques and styles. This convergence of local and international forces has contributed to making Cuban art and artists a major center of artistic excellence and innovation for decades.” - Ben Rodriguez-Cubenas, President & Founder, Cuban Artist Fund“Cuban art is at a level of quality not usually associated with small nations. Cuba has invested greatly in all forms of culture, giving artists greater opportunity support, and reward than most other nations.” - Alex Rosenberg, collector“This highly personal collection of contemporary Cuban art — still in formation -- is guided by passion rather than a specific curatorial vision, but it already highlights a universally agreed-upon characteristic of Cuban art: it’s incredible diversity. -Marilyn Zeitlin, curator

The show’s curator, Sandra Levinson, explains that Cuban contemporary artists come from a unique place: a country embargoed by our own because of its socialist revolution which came to power fifty years ago.

All of the artists in this collection grew up in socialist Cuba, and many of them, such as Franklin, Yamilys and Jacqueline Brito, Zaida del Rio, Carlos Estévez, Kdir and Fernando Rodríguez, graduated from the prestigious Instituto Superior de Arte, built at the beginning of the revolution.

Others, like Alicia Leal, Sandra Ceballos, Rocío García, Mendive, Elsa Mora, William Pérez and Mabel Poblet, attended Havana’s equally excellent San Alejandro Art Academy or other local art schools.

Many, like Lazo, Montebravo, Wayacón, Cornelio, Osés and Villalvilla, are self-taught. Yet despite their disparate backgrounds, aesthetic sensibilities, subject matter, materials and styles, there is something uniquely Cuban about the art in this collection.

Many who try to explain what is uniquely Cuban about this art settle on terms like “magic realism,” or simply “magic” or even “surreal.” In trying to describe Cuban art, many end up simply describing Cuba: it is the island itself that is magic, surreal, a unique blending of spirituality and non-believers, of religion and agnostics, of laughter and pain, of order and chaos.

Alejandro Lazo. Y No Para Cortar el Césped, 2008. Acrylic on canvas. 32 x 39 inches.

Both the island and the art are an unusual mix of the traditional and the modern, of the ordinary and the special, of simplicity and incredible complexity. It goes for the politics, the literature, the architecture, the people, and the art. It befuddles and entrances, is rejecting and embracing.

In Cuba, all is black and white, never grey. The door is always wide open or shut, never ajar. Subtlety is absent in magic, there are few hidden messages. The Cubans are remarkably straightforward and engaging — and so is their art.

For Shelley and Donald Rubins, collecting art is a passion that has evolved out of travel and curiosity about daily life in faraway places. With their newest collection of Cuban art, the Rubins are keenly aware of the connection between supporting living artists and the preservation of culture.

The Oglethorpe University Museum of Art comprises two spacious galleries and occupies some 7,000 square feet. Located in Atlanta and founded in 1835, Oglethorpe University is today an international institution that enrolls over 1,000 students representing 34 states and 36 countries.

Shelley and Donald Rubin are to be commended for their dedication to the arts and society. Such thought leaders and global citizens are what make New York City unique, and their thoughts, passions, and stewardship travel from Lhasa to Havana to Atlanta.

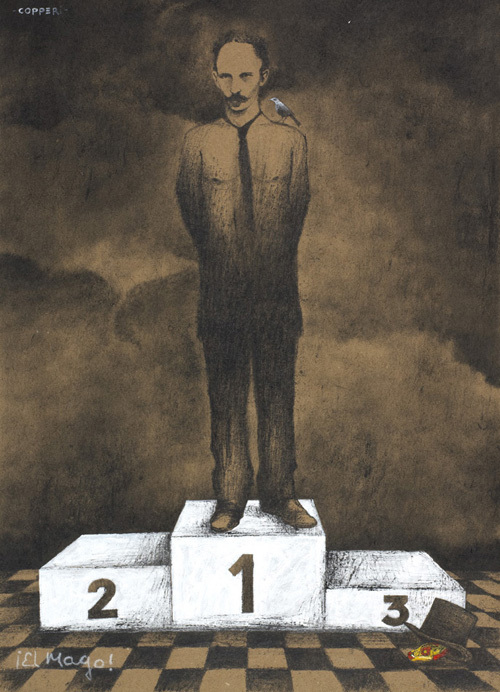

Luis Alberto Pérez Copperi. Patriotismo sin Limites, N.D.

Charcoal on kraft paper. 27 1/2 x 19 3/4 inches.

The Rubins on “What is Cuban Art?” (Originally published in The Huffington Post, March 18, 2010)