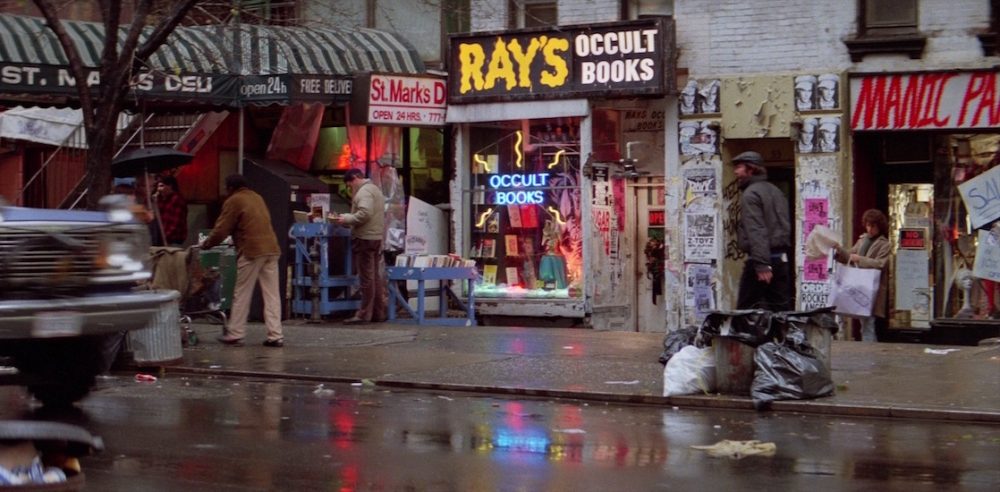

My First Private Room in New York City was on St. Mark’s Place in the East Village, 1983

New York, N.Y. — In 1983, I moved to 48 St. Mark’s Place as my first foothold in New York City, discovering a street that epitomized American counterculture. From elegant 19th-century residences to punk rock venues, this legendary thoroughfare witnessed the evolution of artistic rebellion, political activism, and cultural transformation that defined modern America.

The Foundation of a Cultural Legend

In 1983, I arrived at 48 St. Mark’s Place as my first foothold in New York City. This building housed the Iglesia Metodista Unida Todaslas Naciones (Church of All Nations), pastored by my college friend, Rev. Hal.

Originally the First German Methodist Episcopal Church, as carved into the façade, the building had transformed from a private dwelling. I occupied the top floor—a former maid’s room—for $200 per month.

St. Mark’s Place derives its name from the nearby Episcopal St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery, New York City’s oldest site of continuous religious practice since the mid-17th century. This church became my spiritual home during my East Village stay.

According to Eric Ferrara, New York City historian and founder of the Lower East Side History Project, St. Mark’s Place evolved from an elegant residential district in the early 19th century to a hub of counterculture and artistic expression in the 20th century.

In the early 1800s, Federal and Greek Revival townhouses attracted wealthy residents. However, by the mid-19th century, German immigrants transformed the area into “Kleindeutschland” (Little Germany), replacing elegant homes with tenement housing and boarding houses.

A Constellation of American Cultural Icons

St. Mark’s Place became home or host to an extraordinary collection of American cultural figures who shaped the nation’s artistic and political landscape.

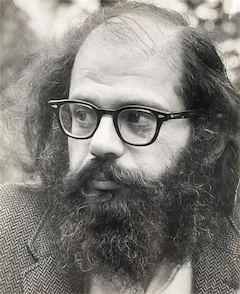

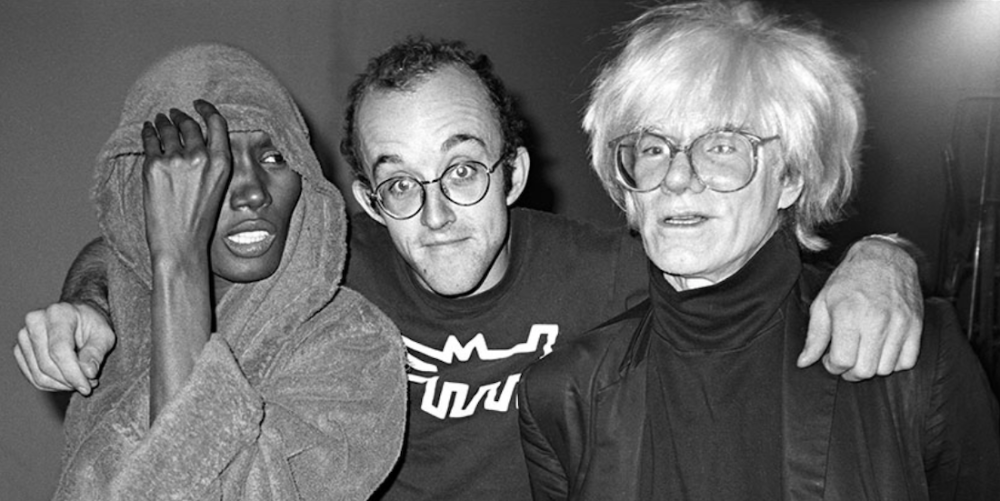

Allen Ginsberg, Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, Jonas Mekas, Andy Warhol, Paul Morrissey, Jimi Hendrix, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, Kenny Scharf, Lenny Bruce, Klaus Nomi, Joey Arias, and Lypsinka all called this street home or performed here regularly.

Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols was a frequent visitor, though he lived in Chelsea.

Bands including The Fugs, The Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, and the Fleshtones—a garage rock band from Queens that debuted at the East Village‘s CBGB in 1976—performed on this legendary street.

Historical references include activist Emma Goldman, comedian Lenny Bruce, historian Will Durant, and crooner Frank Sinatra.

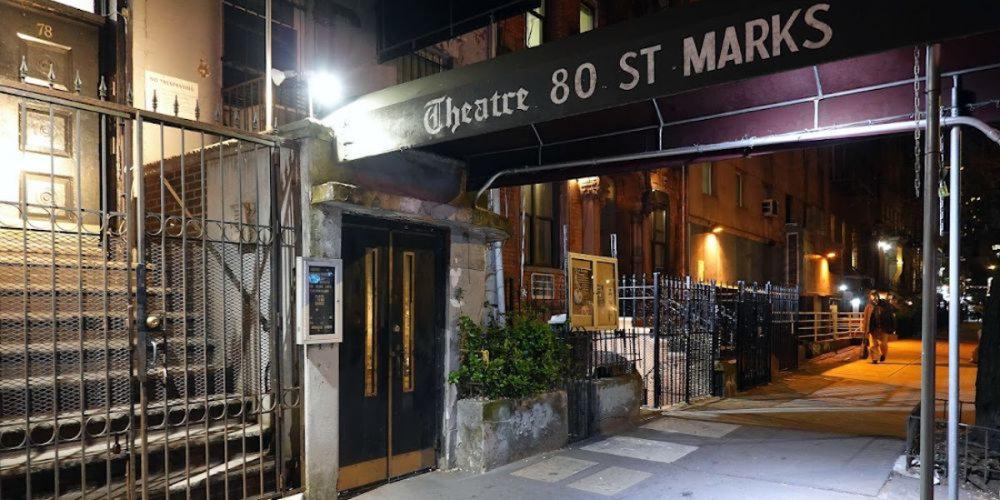

The Theatre 80 St. Mark’s features a walk-of-fame sidewalk signed by Joan Crawford, Gloria Swanson, Myrna Loy, Kitty Carlisle, and Dom DeLuise.

Revolutionary Venues and Artistic Expression

4 St. Mark’s Place, built as a residence for Alexander Hamilton’s son in 1831, evolved into a hotbed of avant-garde art and countercultural performances. The Bridge Theater pushed boundaries during the Vietnam War era, hosting luminaries such as Yoko Ono.

In 1965, the theater drew official attention for screening “Flaming Creatures,” a controversial film by Jack Smith. The organizer, Jonas Mekas, was arrested, and the film was labeled “obscene” by the court. The following year, controversy erupted when an American flag was burned during a performance, though charges were later dropped.

The Modern School occupied 6 St. Mark’s Place in 1911, an educational institution founded on progressive, libertarian principles. The school’s mission emphasized critical thinking, creativity, and social awareness for working-class individuals.

Founders included prominent anarchists such as Emma Goldman, whose activism extended to controversial acts, including suspected involvement in the 1901 assassination attempt on President William McKinley.

Goldman’s advocacy led to her arrest and deportation in 1919 due to her “dangerous” political views.

Philosopher Will Durant, who later became famous for “The Story of Civilization,” served as principal, implementing hands-on, experimental learning approaches that resembled modern democratic education models.

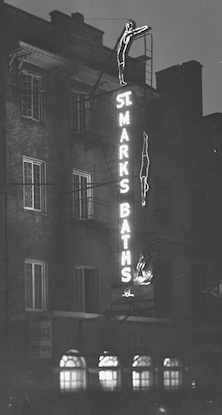

The Saint Marks Baths: A Cultural Landmark

The Saint Marks Baths opened in 1913 at 6 St. Mark’s Place, originally operating as a Victorian-style Turkish bath catering to the neighborhood’s Russian-Jewish immigrant population. By the 1950s, the clientele evolved. During the day, it maintained its traditional role, but by night, it discreetly attracted a growing LGBTQ+ clientele.

By the 1960s, the Saint Marks Baths fully embraced this identity, becoming a space exclusively catering to gay men. In 1979, the bathhouse underwent significant refurbishment and was rebranded as the New Saint Marks Baths, introducing modern amenities and solidifying its place as a premier destination within the LGBTQ+ community.

The bathhouse’s significance extended beyond leisure—it became a cultural landmark of the East Village and a symbol of the sexual liberation movement of the 1970s and early 1980s. However, its legacy was complicated by the AIDS crisis in the mid-1980s, which profoundly reshaped attitudes toward such spaces.

In later decades, the building housed Kim’s Video, a beloved institution for cinephiles specializing in rare and independent films. Founded by Korean immigrant Yongman Kim, it began as a small electronics shop but quickly became known for its video rentals and rare, hard-to-find films.

Comedy and Free Speech: Lenny Bruce’s Legacy

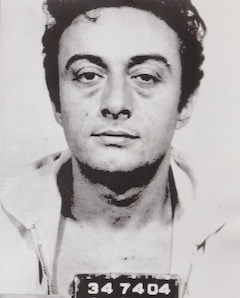

In the 1960s, comedian Lenny Bruce lived at 13 St. Mark’s Place.

Bruce was a cultural icon known for pushing the limits of free speech and challenging conventional comedy standards.

His career was marked by controversy and frequent arrests on obscenity charges.

In Cold War America, Bruce’s bold content led to multiple arrests across the U.S., culminating in a 1964 obscenity trial at the New York State Supreme Court.

Before the trial concluded, Bruce died from a supposed drug overdose—though his enemies were numerous and capable of violence.

In 2003, nearly forty years later, New York State granted him a posthumous pardon, the first of its kind in the state, symbolizing recognition of his fight for free speech.

The Yippie Movement and Political Activism

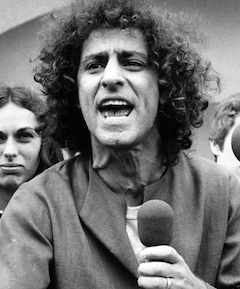

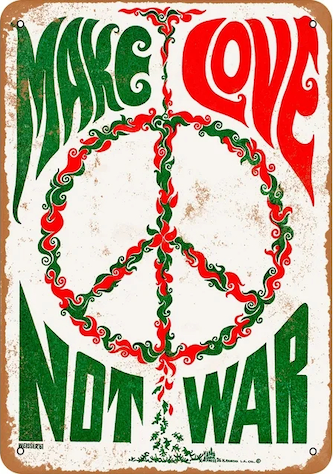

St. Mark’s Place became a hub for the Yippie movement (Youth International Party), a radical counterculture group that emerged in the late 1960s. Yippies advocated for freedom of expression, anti-war protest, and anti-establishment values, often blending satire with political activism.

By 1967, Abbie Hoffman lived at 30 St. Mark’s Place, where he and his first wife, Anita Kushner, launched the Youth International Party.

Dissatisfied with what he viewed as the overly passive nature of the Hippie movement, Hoffman sought to inject more provocative and confrontational energy into activism.

One of Hoffman’s memorable stunts involved planting a tree at the corner of Third Avenue and St. Mark’s Place, causing a traffic jam that lasted hours.

Another famous act took place at the New York Stock Exchange, where Hoffman threw $1,000 in $1 bills onto the trading floor, leading to significantly tightened security protocols.

Hoffman’s activism culminated in the protests at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, where he was accused of conspiracy and inciting riots. This led to his trial as part of the Chicago 7. Bill Kunstler, who later worked with our organization “Fundamentalists Anonymous” in the mid-1980s, served as the flamboyant lead defense attorney.

The Dom and Electric Circus: Music Revolution

The popular restaurant known as The Dom became central to the music revolution. In the 1960s, Stanley Tolkin ran Stanley’s Bar downstairs, featuring bands like The Fugs, while the upstairs was rented for psychedelic light shows.

In 1966, Andy Warhol and Paul Morrissey transformed the upstairs space into The Dom nightclub, with The Velvet Underground as the house band. The venue later became Electric Circus, a legendary psychedelic nightclub that hosted major acts like Jimi Hendrix, The Grateful Dead, and Jefferson Airplane.

Underground Commerce and Counterculture

From 1967 to 1971, Underground Uplift Unlimited (UUU) occupied 28 St. Mark’s Place, becoming a cultural icon of the 1960s counterculture movement.

UUU produced and sold iconic buttons and posters with slogans like “Make Love, Not War” and “More Deviation, Less Population,” becoming the largest seller of protest pins in the country.

In the 1980s, 33 St. Mark’s Place housed Manic Panic, a pioneering punk-rock boutique founded by Bronx-born sisters Tish and Snooky Bellomo.

Former backup singers for Blondie, the sisters opened the store in 1977, making it one of the first punk shops in America. Their neon hair colors and unconventional makeup revolutionized alternative beauty and became cultural touchstones for rockers, goths, and rebels worldwide.

Art Galleries and Cultural Hubs

By the early 1980s, 51 St. Mark’s Place had transformed into 51X, an influential contemporary art gallery that became a key venue in the rise of Urban Contemporary Art, also known as Graffiti Art. The gallery showcased works by Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, and even Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols.

57 St. Mark’s Place housed Club 57, one of the most famous and influential venues in the city’s counterculture movement. Managed by Anne Magnuson, the club became a hub for art, music, and creative expression, embodying the DIY, anti-pop culture aesthetic of the era.

Literary and Intellectual Heritage

In the 1950s, poet W.H. Auden lived at 77 St. Mark’s Place, where he wrote much of his later work, including parts of his “Collected Poems.”

Auden moved to the United States in 1939, fleeing the rising fascist threat in Europe, and became a naturalized American citizen in 1946.

The Beat Generation was also a regular presence at the Holiday Lounge, with Allen Ginsberg and other members of the Beatnik movement frequenting the establishment during the 1950s and early 1960s.

In the early 20th century, the basement of 77 St. Mark’s Place was home to Sovremenny Mir (“Contemporary World”), a Russian-language, pro-Communist newspaper.

Lev Davidovich Bronstein, better known as Leon Trotsky, worked for the publication during his time in New York in 1917.

Trotsky was a central figure in the Russian Revolution and one of the most iconic revolutionaries of the 20th century.

The Squat Culture and Urban Decay

120 St. Mark’s Place was likely the last active squat on the Lower East Side, remaining so until summer 2006, when residents, including the famed “Mosaic Man” Jim Power, were evicted.

I remember frequently seeing Jim building mosaics on lamp post bases in and around St. Marks.

By the 1980s, the East Village—particularly Alphabet City—had become home to over 200 active squats, providing shelter to hundreds of squatters.

This surge in squatting resulted from New York City’s severe economic recession during the late 1970s and early 1980s, which brought the city to the brink of bankruptcy under Mayor Edward Koch’s administration.

By the early 1980s, nearly 30% of Alphabet City was abandoned, with entire blocks left to decay as landlords fled their properties.

Contemporary Legacy

94 St. Mark’s Place houses Fun City Tattoo & Cappuccino, celebrated as the oldest operating tattoo parlor in New York City, dating back to 1976. It played a significant role in the city’s tattooing renaissance, particularly during the period when tattooing was illegal.

The building at 77 St. Mark’s Place became Theater 80 in the 1960s, producing dance performances, ballets, and musicals. In 1967, it was the venue for the premiere of “You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown.” Outside the theater, on the sidewalk, is a mini-Off-Broadway Walk of Fame featuring handprints, footprints, and signatures of notable 20th-century actors and actresses.

St. Mark’s Place remains a testament to American cultural evolution, where artistic rebellion, political activism, and social transformation converged to create one of the most significant cultural corridors in U.S. history.

From Emma Goldman’s anarchist activism to Jean-Michel Basquiat’s groundbreaking art, from Lenny Bruce’s fight for free speech to Abbie Hoffman’s theatrical protests, this single street witnessed and nurtured the forces that reshaped American culture.

The legacy of St. Mark’s Place extends far beyond its physical boundaries, representing the ongoing struggle between establishment and counterculture, between conformity and artistic expression, between the past and the future.

As I walked through Alphabet City in January 1983, seeing people burning trash in bins to stay warm, I realized I was witnessing not just urban decay, but the raw material from which American cultural renaissance would emerge.

St. Mark’s Place: A Cultural Revolution in New York’s East Village (July 12, 2025)