Allied forces retained the Nazi-amended Paragraph 175, excluding homosexual prisoners from victim status. Thousands remained jailed as police and judges from the Third Reich persisted.

New York, N.Y. — In the shadow of the Nuremberg Trials, a quieter injustice unfolded. While the Allies dismantled the Nazis’ political machinery, they left intact one toxic legacy: Paragraph 175.

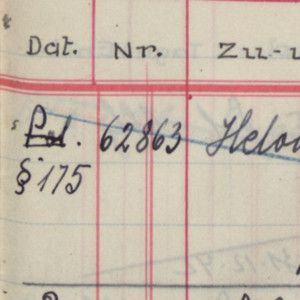

This statute, which criminalized homosexuality, had been intensified under Adolf Hitler to mandate harsher sentences, castration, and deportation to concentration camps. Yet in 1945, the occupying powers—the U.S., U.K., France, and the Soviet Union—chose not to repeal it. For gay survivors of Nazi terror, liberation meant trading pink triangles for prison cells.

The Legal Betrayal

The original 1871 German law punished “unnatural indecency” between men. The Nazis broadened it in 1935 to include any act deemed “lewd,” even glances or touches.

Post-war, the Allies paradoxically reinstated pre-Nazi civil codes but kept the Nazi-era Paragraph 175. West Germany, East Germany, and Austria upheld it, arguing homosexuality was inherently criminal—not a Nazi-specific persecution.

Consequently, gay prisoners were ineligible for reparations or victim of fascism pensions. Many completed sentences imposed by Hitler’s courts; others faced new charges under the same law.

Faces of the Forgotten

Heinz Dörmer spent 12 years in Sachsenhausen and Buchenwald under the Nazis. In 1950, he was arrested again under Paragraph 175, serving two more years. “The judge sneered, ‘You haven’t learned your lesson?’” Dörmer later recalled.

Police files from the Third Reich were reused to target gay men, while former Nazi officers retained judicial roles. Survivors faced an agonizing choice: conceal their past or risk exposure in a society where neighbors, employers, and police viewed them as criminals.

The Cost of Silence

Psychiatrist Dr. Lotte Köhler documented cases of severe trauma among clients who buried their histories. “One patient called it ‘double extermination’—first by the camps, then by erasure,” she wrote.

Without victim status, men were barred from medical care for camp injuries, financial aid, or refugee programs. Some emigrated to America but faced deportation under the U.S.’s own anti-homosexuality immigration laws. In Austria, where Paragraph 175 remained until 1971, arrests peaked in the 1950s.

Seeds of Resistance

Activist groups like Hamburg’s Humanitarian Society (founded by gay survivors in 1949) petitioned governments to recognize Nazi-era persecution. They were met with silence or ridicule.

West Germany’s 1956 Federal Compensation Law explicitly excluded Paragraph 175 convicts, citing “moral guilt.”

Not until 2002 did the German parliament issue a formal apology; reparations claims were largely denied due to “expired” statutes of limitation.

Silenced Liberation: Gay Nazi Victims Denied Reparations After World War II (July 24, 2025)

Audio Summary (75 words)

After World War II, the Allies preserved the Nazi-amended Paragraph 175, denying reparations to gay Holocaust survivors. West Germany, East Germany, and Austria imprisoned men under the same law used by the Nazis, reusing Third Reich police files. Victims faced societal stigma or hiding their past. Activist efforts were ignored until a 2002 apology, though most reparations claims were rejected. This legal betrayal prolonged persecution for thousands.