For three brutal months in 1937, China’s best troops fought block-by-block against Japan, sacrificing themselves to buy time as Shanghai burned — paving the road to Nanking

New York, N.Y.—The image of a wailing Chinese baby amid the smoldering ruins of Shanghai South Railway Station, published in Time Magazine on September 4, 1937, shocked the world.

Dubbed “Bloody Saturday,” photographer H.S. Wong’s searing composition captured the aftermath of a Japanese aerial bombing that killed his mother and left 136 million viewers confronting the human cost of Asia’s unfolding war. This moment crystallized the agony of Shanghai—once Asia’s glittering “Paris of the East“—during a 13-week battle that historians now call the “Stalingrad on the Yangtze.”

The Spark That Ignited Inferno

The Battle of Shanghai erupted on August 13, 1937, after simmering tensions exploded with the Ōyama Incident. On August 9, Japanese Naval Lieutenant Isao Ōyama and his driver were killed near Hongqiao Airport under disputed circumstances. Japan demanded China withdraw its Peace Preservation Corps; China refused.

Within days, 300,000 Japanese troops backed by 500 aircraft and 300 tanks faced off against 700,000 Chinese defenders. General Iwane Matsui, commanding Japan’s forces, predicted victory in three days. Instead, Chiang Kai-shek’s German-trained divisions fought with ferocity that stunned Tokyo.

Urban warfare turned the city into a charnel house. Chinese soldiers, lacking armor or air support, used close-quarters combat to neutralize Japan’s technological edge. “The Japanese would be forced into rat warfare,” noted historian Peter Harmsen, referencing the brutal house-to-house fighting that presaged Stalingrad. Japanese forces deployed poison gas at least thirteen times illegally against entrenched Chinese positions, yet the defenders held.

By October, Shanghai’s waterways ran red—Chinese casualties

exceeded 187,200, while Japan suffered 18,800 combat deaths.

City of Refugees and Rubble

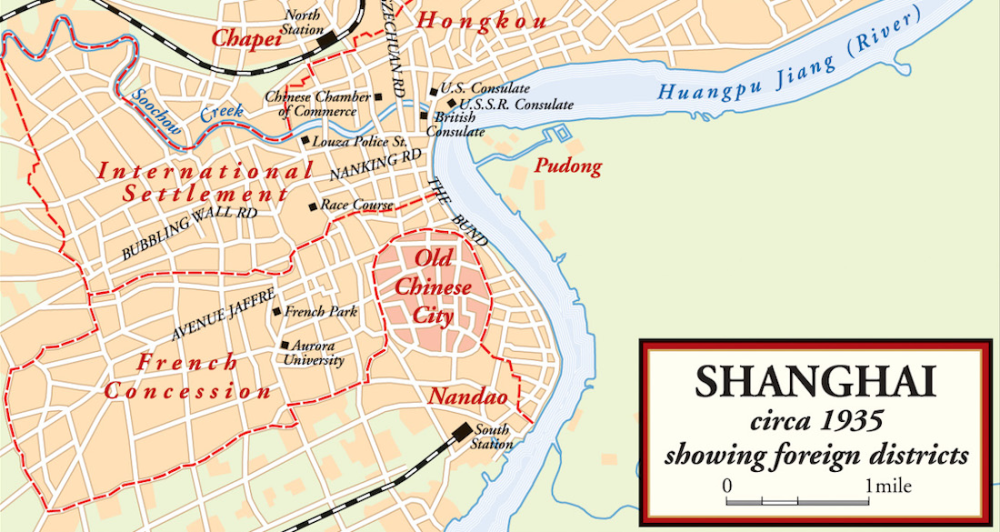

Shanghai’s transformation from cosmopolitan jewel to apocalyptic wasteland displaced over a million civilians. Fleeing relentless bombardment, they flooded into the International Settlement and French Concession, cramming 180,000 people per square mile. Theaters became makeshift dormitories; families slept in shifts. Relief organizations like the Shanghai International Relief Committee scrambled to provide food and medical care amid cholera outbreaks.

The battle also reshaped Shanghai’s demographic tapestry. By 1938, Jewish refugees from Nazi Europe joined 50,000 Russian Jews already settled there. Concentrated in Hongkew district—a bombed-out shell—they relied on the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee for survival while navigating Japanese occupation policies. Their presence underscored Shanghai’s tragic duality: a haven for some, a hell for others.

The Road to Nanking

When Shanghai finally fell on November 12, Japan’s triumphalism curdled into vengeful fury. The protracted battle had shattered myths of Chinese inferiority and cost Japan dearly. As one veteran confessed, soldiers carried “bitter resentment” westward toward Nanking.

What followed was a campaign of terror. New York Times correspondent F. Tillman Durdin reported from the fallen capital: “Wholesale looting, the violation of women, the murder of civilians… mass executions of war prisoners turned Nanking into a city of terror.”

Historians now recognize Shanghai’s fall as the catalyst for the Rape of Nanking.

Chinese troops, depleted and demoralized, retreated chaotically. Japan’s advance became a blitzkrieg of atrocities, with soldiers methodically executing civilians. On December 13, Durdin witnessed 200 Chinese men gunned down on the Bund: “The killings took ten minutes… Japanese pumped bullets into any that still kicked.” By February 1938, an estimated 200,000–300,000 lay dead.

Legacy in the Ashes

The Battle of Shanghai achieved China’s strategic goal—delaying Japan’s advance to allow industrial evacuation—but at catastrophic human cost. Its urban warfare tactics became a grim blueprint for World War II, while the Nanking Massacre remains a flashpoint in East Asian relations.

As Chicago Daily News journalist Archibald Trojan Steele cabled from Nanjing: “The last thing we saw as we left the city was a band of 300 Chinese being methodically executed.

Today, ruins like the Bazi Bridge where the first shots were fired stand as silent witnesses to a battle that redefined modern combat—and foreshadowed the century’s darkest impulses.

Shanghai’s Fall: The Stalingrad of Yangtze That Preceded Nanking’s Horror (June 22, 2025)