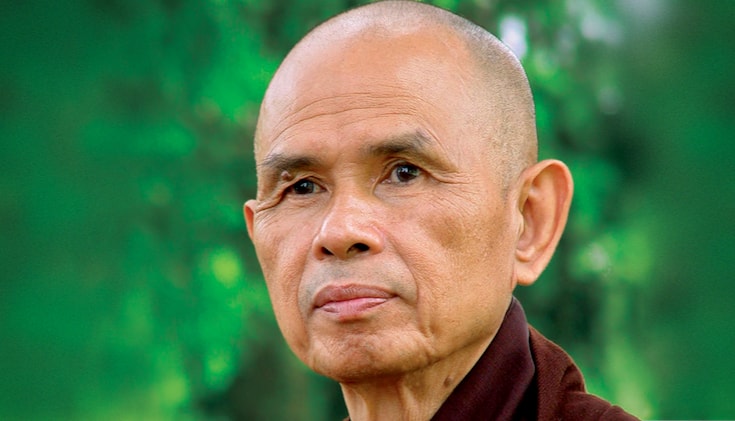

Thich Nhat Hanh, the Vietnamese Buddhist monk and founder of the Engaged Buddhism movement, died January 22 in his home country of Vietnam. He was 95.

San Francisco, CA. One of the great Buddhist teachers of our time, Thich Nhat Hanh died today at Tu Hieu Pagoda in Vietnam, the Buddhist temple where he was ordained at age sixteen. Following his stroke in 2014, he had expressed a desire to return to his homeland, and, in October 2018, moved back to his home temple. There, he spent the last years of his life surrounded by his close disciples and students.

The International Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism released a statement announcing Nhat Hanh’s passing, followed by a schedule of live-streamed memorial ceremonies honoring their teacher to be broadcast through the week from Hue, Vietnam and Plum Village, France.

Nhat Hanh, affectionately referred to as “Thay,” by his students, has often been referred to as “the father of mindfulness.” In his 95 years, he made a global impact as a teacher, author, activist, and the founder of the Engaged Buddhism movement. His simple yet deeply profound teachings led countless people towards a life of mindfulness, joy, and peace.

Nhat Hanh suffered a brain hemorrhage in November 2014 and spent four-and-a-half months at a stroke rehabilitation clinic at Bordeaux University Hospital, after which he returned to Plum Village in France, where he was able to enjoy being “out in nature, enjoying the blossoms, listening to the birds and resting at the foot of a tree.” In July of 2015, Nhat Hanh traveled to the United States for intensive rehabilitation at San Francisco’s UCSF Medical Center. In January 2016, he returned again to Plum Village, France to be with the sangha, as shared in an update on his 92nd birthday.

In 2016, two months after his 90th birthday, Nhat Hanh expressed a wish to travel to Thailand to be closer to his homeland of Vietnam. He spent nearly two years at Thai Plum Village. In October 2018, Thich Nhat Hanh traveled to Vietnam to spend the remainder of his days at his root temple.

Nhat Hanh was born Nguyen Xuan Bao in Hué, Vietnam in October of 1926. Interested in Buddhism from an early age, he entered the monastery at Tu Hieu Temple in Vietnam at sixteen. There, he worked with his primary teacher, Zen master Thanh Quy Chan That. In 1951, Nhat Hanh was ordained as a monk after receiving training in Vietnamese Mahayana and Thien Buddhist traditions. It was then that he received the name Thich Nhat Hanh.

As Lindsay Kyte reported for Lion’s Roar in “The Life of Thich Nhat Hanh,” Nhat Hanh was sent for training at a Buddhist academy but was dissatisfied with the curriculum, wanting to study more modern subjects. He left for the University of Saigon, where he could study world literature, philosophy, psychology, and science in addition to Buddhism. He went on to begin his activist work, founding La Boi Press and the Van Hanh Buddhist University in Saigon. He also founded the School of Youth for Social Service, a neutral corps of Buddhist peace workers who established schools, built healthcare clinics, and rebuilt villages in rural areas.

Nhat Hanh accepted a fellowship to study comparative religion at Princeton University in 1960 and was subsequently appointed a lecturer in Buddhism at Columbia University. He had become fluent in English, Japanese, Chinese, Sanskrit, Pali, and English.

In 1963, a U.S.-backed military coup had overthrown the Diem regime, and Nhat Hanh returned to Vietnam to continue initiating nonviolent peace efforts. He submitted a peace proposal to the Unified Buddhist Church (UBC), calling for a cessation of hostilities, the establishment of a Buddhist institute for the country’s leaders, and the creation of a center to promote nonviolent social change.

The founding of the Engaged Buddhism movement was his response to the Vietnam War.

Nhat Hanh’s mission was to engage with the suffering caused by war and injustice and to create a new strain of Buddhism that could save his country. In the formative years of the Engaged Buddhism movement, Nhat Hanh met Cao Ngoc Phuong, who would later become Sister Chan Kong. She hoped to encourage activism for the poor in the Buddhist community, and worked closely with Nhat Hanh to do so. She remained his closest disciple and collaborator for the remainder of his life.

In 1966, Nhat Hanh returned to the U.S. to lead a symposium at Cornell University on Vietnamese Buddhism. There, he met with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and asked King to denounce the Vietnam War. Dr. King granted the request the following year with a speech questioning America’s involvement in the war. Soon after, he nominated Nhat Hanh for the Nobel Peace Prize. “I do not personally know of anyone more worthy of [the prize] than this gentle monk from Vietnam. His ideas for peace, if applied, would build a monument to ecumenism, to world brotherhood, to humanity,” he wrote.

In June of that year, Nhat Hanh presented a peace proposal in Washington urging Americans to stop bombing Vietnam, emphasizing that he and his followers favored neither side in the war and wanted only peace. In response, Nhat Hanh was exiled from Vietnam. He was granted asylum in France, where he became chair of the Vietnamese Buddhist Peace Delegation.

Nhat Hanh was the head the Order of Interbeing, a monastic and lay group that he founded in 1966. In 1969, he also founded the Unified Buddhist Church, and later in 1975, formed the Sweet Potatoes Meditation Center southeast of Paris, France. As the center grew in popularity, Nhat Hanh and Sister Chan Khong founded Plum Village, a vihara (Buddhist monastery) and Zen center, in the South of France in 1982.

In 1987, he founded Parallax Press in California, which publishes his writings in English. He established Deer Park Monastery in Southern California, his first monastery in America, in 2000. Since then, many dharma centers across the U.S., serving tens of thousands of lay students, have been established as part the Order of Interbeing.

After negotiations, the Vietnamese government allowed Nhat Hanh, now a well-known Buddhist teacher, to return to Vietnam for a visit in 2005. He was able to teach, publish four books in Vietnamese, travel the country, and visit his root temple. Although his first trip home stirred controversy, Nhat Hanh was allowed to return again in 2007 to support new monastics in his Order, organize chanting ceremonies to heal wounds from the Vietnam War, and lead retreats for groups of up to 10,000.

“We gauge the greatness of spiritual teachers by the depth, breadth, and impact of their teachings, and by the example their lives set for us. By all these measures, Thich Nhat Hanh is one of the leading spiritual masters of our age,” writes Lion’s Roar editor-in-chief Melvin McLeod in his introduction to The Pocket Thich Nhat Hanh.

In his lifetime, Nhat Hanh authored more than 100 books, which have been translated into 35 languages, on a vast range of subjects — from simple teachings on mindfulness to children’s books, poetry, and scholarly essays on Zen practice. His most recent book, Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet, was published by HarperCollins in October 2021. His community consists of more than 600 monastics worldwide, and there now exists more than 1000 practice communities attended by his dedicated sangha across North America and Europe.

It is estimated that Nhat Hanh created over 10,000 works of calligraphy in his life, each sharing unique, simple messages: “Breathe, you are alive”; “Happiness is here and now”; “Present moment, wonderful moment”; “Wake up; It’s now”; “This is it”. His life itself was a meditation in action, creating peace with every step.

In a newsletter to the community, Plum Village shared that starting Saturday, January 22, the global community is invited to come together online to commemorate Thich Nhat Hanh’s life and legacy. Plum Village will broadcast five days of practice and ceremonies live from Hue, Vietnam and Plum Village, France. More details can be found on their website.

“Now is a moment to come back to our mindful breathing and walking, to generate the energy of peace, compassion, and gratitude to offer our beloved Teacher. It is a moment to take refuge in our spiritual friends, our local sanghas and community, and each other,” Plum Village writes.

In his book, At Home in the World, published in 2016, Nhat Hanh addressed his inevitable death. He wrote:

This body of mine will disintegrate, but my actions will continue me… If you think I am only this body, then you have not truly seen me. When you look at my friends, you see my continuation. When you see someone walking with mindfulness and compassion, you know he is my continuation. I don’t see why we have to say “I will die,” because I can already see myself in you, in other people, and in future generations.

Even when the cloud is not there, it continues as snow or rain. It is impossible for the cloud to die. It can become rain or ice, but it cannot become nothing. The cloud does not need to have a soul in order to continue. There’s no beginning and no end. I will never die. There will be a dissolution of this body, but that does not mean my death.

I will continue, always. – Lilly Greenblatt

Lilly Greenblatt is the digital editor of LionsRoar.com. You can find more about her at lillygreenblatt.com.

Stewardship Report Editor’s Note: Thich Nhat Hanh has been ranked 98/100 according to the Luce Index™.

Remembering Thich Nhat Hanh (1926-2022) (Jan. 21, 2022)