Nālandā had eight separate compounds and ten temples, along with meditation halls and classrooms. On the grounds were lakes and parks.

Who knew? The first great university in recorded human history was Buddhist and in India — 500 years B.C. — and destroyed by Islamic invaders in 1193.

Bihar, India. The next stop of our pilgrimage is the ancient center of higher learning, Nālandā. Unknown to me before in New York, the Buddhists built the first great university in recorded human history. Established around 500 BC, it had over 10,000 students and 2,000 teachers from around the world. The library was located in a nine storied building where meticulous copies of texts were produced. It contained over fifty million books and documents – more than the Ivy League libraries of Harvard, Yale, Columbia, and Cornell combined! Tragically, in 1193 the city was conquered and destroyed by Islamic forces, causing the decline of Buddhism in India. The name Nālandā means, “insatiable giving.”

— 500 years B.C. — and destroyed by Islamic invaders in 1193.

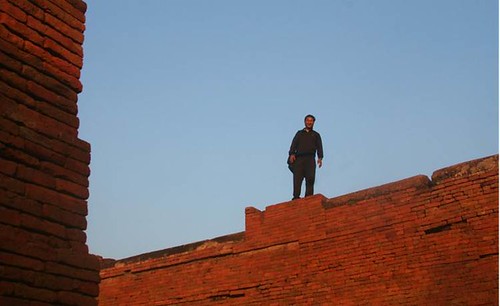

The complex was built with red bricks – ubiquitous to this area of India, with brick factories still doting the countryside – and its ruins occupy an area of 35 acres. This is estimated at only ten percent of its original 350 acres – about the total size of Harvard’s campus today. Nālandā was one of the world’s first residential universities. At its peak, the university attracted scholars and students from as far away as China, Greece, and Ancient Persia. Nālandā was ransacked and destroyed by Islamic invaders in 1193. The great library of Nālandā University had been so vast that it is reported to have burned for three months after the invaders set fire to it. The invaders ransacked and destroyed the monasteries there as well, driving the monks from the site – many of whom fled to Tibet.

Paraphrased from Wikipedia, an always-helpful helpful travel guide (along with my personal favorite Lonely Planet):

“Thousands of monks were slaughtered under Islamic leader Khilji tried to conquer Buddhist Nālandā and plant his rule by the sword. The destruction of the temples, monasteries, centers of learning at Nālandā and northern India to be responsible for the demise of ancient Indian scientific thought in mathematics, astronomy, alchemy, and anatomy.

“The university was considered an architectural masterpiece, and was marked by a lofty wall and one gate. Interestingly, archeologists have yet to find that one gate, so they have carved a gate through an existing wall which provided us entry into the formidable complex. Having tried and failed to photograph the aftermath of the Tsunami – it resembled a gigantic landfill; and how can you capture villages and villagers that are no longer there?

I felt I was not up to the task of capturing images of Nālandā. Nālandā had eight separate compounds and ten temples, along with many other meditation halls and classrooms. On the grounds were lakes and parks. The subjects taught at Nālandā University covered every field of learning, and it attracted pupils and scholars from Korea, Japan, China, Tibet, Indonesia, Persia, and Turkey.

I was stunned to learn that the curriculum of Nālandā University had contained virtually the entire range of world knowledge available at the time. Courses were drawn from every field of learning, Buddhist and Hindu, sacred and secular, foreign and native. Students studied science, astronomy, medicine, and logic as diligently as they applied themselves to metaphysics, philosophy, and the scriptures of Buddhism. They studied foreign philosophy likewise. A vast amount of what came to comprise Tibetan Buddhism, both its Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions, stems from the late (9th–12th century) Nālandā teachers and traditions.

How can the glory days of Buddhism be restored?, I wondered. Luckily, many minds far greater than mine have wondered the same thing: Singapore, China, India, Japan, and several other nations, have announced and proposed to restore and revive the ancient site as Nālandā International University. The New York Times detailed a plan in the works to spend $1 billion to revive Nālandā University near the ancient site: $500 million to build a new university and another $500 million to develop necessary infrastructure.

Photo: author.

It is anticipated that 1,137 international students will enroll in its first year, and 4,530 by the fifth. “Nālandā U.” would largely be a post-graduate research university, with the following schools: Buddhist Studies, Philosophy and Comparative Religion; Historical Studies; International Relations and Peace; Business Management and Development; Languages and Literature, as well as the School of Ecology and Environmental Studies. How grand is that? The objective of the school will be aimed at advancing the concept of a pan-Asian community and rediscovering their magnificent roots.

Of course, modern Muslims are as responsible for the sacking of Nālandā as I am for the Crusades. His Holiness the Dalai Lama has had contact with Islamic and other faith leaders around the world for many years. For example, Dr. Alexander Berzin, a Turkish expert in Tibetan Buddhist traditions, and Dr. Tirmiziou Diallo, the hereditary Sufi religious leader of Guinea, traveled to Dharamshala to meet with the Dalai Lama. In the days prior to the audience, he and Dr. Berzin discussed further the meaning of “people of the Book.” Dr. Diallo felt it refers to people who follow the “Primordial Tradition.”

This can be called the wisdom of Allah or God, or in Buddhist terms, primordial deep awareness. Thus, he readily accepted that the primordial tradition of wisdom was revealed not only by Moses, Jesus, and Muhammad, but also by Buddha. If people follow this innate primordial tradition and wisdom, they are “people of the Book.” But, if they go against this basic good and wise nature of humankind and the universe, they are not of the “Book.”

On the last day of his visit, Dr. Diallo had his private audience with the Dalai Lama. Dressed in elegant white robes, the majestic African spiritual leader was so moved upon first being in His Holiness’s presence, he began to weep. Without asking his attendant as he normally would, the Dalai Lama personally went to his anteroom and brought back a tissue, which he offered the Sufi master to wipe his tears. Dr. Diallo presented His Holiness with a traditional Muslim headdress, which His Holiness put on without hesitation and wore for the remainder of the audience.

His Holiness opened the dialogue by explaining that if both Buddhists and Muslims remain flexible in their thinking, fruitful and open dialogue is possible. The encounter was extremely warm and emotionally touching. His Holiness asked numerous questions about the Sufi meditation tradition, specifically concerning the West African lineages that emphasize the practice of love, compassion, and service. Dr. Diallo had been living in exile for many years in Germany after a communist takeover of his country. There were many things in common that the two men shared. Both His Holiness and Dr. Diallo pledged to continue the Islamic-Buddhist dialogue in the future.

Attending the Kalachakra in Bodhgaya, India with His Holiness The Dalai Lama, I am hearing a constant message that modern Buddhists must embrace academic achievement and international enlightenment and interfaith dialogue as much as Enlightenment itself. I applaud all efforts to help move all nations and peoples – Buddhist or not – forward through higher education.

Rediscovering the World’s First Great University in Buddhist India (Originally published in Daily Kos, Jan. 17, 2012)