Little did we suspect that, under this dignified bearing and polished manner, lay concealed the military spirit of one of the most warlike races of all time.

Washington, D.C. — Wikipedia writes in it’s entry on the U.S.S. Columbus, “After embarking Commodore James Biddle, Commander, East India Squadron, she sailed on 4 June 1845 for Canton, China, where on 31 December Commodore Biddle exchanged ratified copies of the first American commercial treaty with China. Columbus remained there until April 1846, when she sailed for Japan to attempt opening that country to American commerce. She raised Uraga Channel on 19 July in company with Vincennes, but achieved no success.”

The truth is that the mission was an utter failure. The U.S.S. Columbus and its companion ship U.S.S. Vincennes were immediately surrounded by dozens of Japanese boats when they entered Tokyo Harbor, then called Edo Bay as well as Yeddo Bay. It took a month for their written request to the Emperor to open commerce between Japan and America to reach him and return an answer. The answer was no. All commerce, he stated, was between Japan and the Dutch only – and solely conducted through the harbor village of Nagasaki far to the south of Tokyo (Edo). The two ships were then escorted with over 100 Japanese boats back out to sea.

Seven years later Commander Matthew Calbraith Perry. Perry, like his predecessor, sailed direct to Yedo Bay to carry on negotiations, but, unlike Biddle, he adopted an extremely formal tone, allowing no Japanese except officials of considerable rank on board and refusing audience to any below the grade of cabinet minister. Perry’s exclusiveness and great formality encouraged the Japanese to open their “hermit kingdom’ to the United States, ending the Meiji Era and isolation.

U.S. Navy Rear Admiral Stephen Bleecker Luce, founder of the Naval War College, wrote in the Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute, Annapolis (vol. xxxi-31, 1905) about his 1846 voyage as a midshipman in his youth with Commodore James Biddle to Edo Bay — modern Tokyo — seven years before Admiral Perry‘s better known voyage that opened Japan and ended the feudal era there in 1853.

Commodore Luce wrote,

“The influence of the West upon the ancient civilization of Japan, and the phenomenal progress made by that country toward becoming a formidable naval power, furnishes one of the most remarkable epochs of modern times.”

Luce continued, “Any account, however dry and meagre, detailing the earlier steps taken by the government of the United States to cultivate friendly relations with that wonderful country must prove of more or less interest.

“As far as can be ascertained from official sources the question of the United States government opening communication with Japan with a view to negotiating a treaty of commerce originated with Mr. Caleb Cushing, one of the most eminent jurists and scholars of his day.

“In 1843, Mr. Cushing was appointed commissioner to China and negotiated the first treaty between the United States and that Empire.

“During his sojourn in China Mr. Cushing conceived the idea that Japan might be induced to follow the example of China and throw open her ports to American commerce. His views on the subject were communicated to the President.

“In answer to his letter he received the following reply from the Secretary of State, Mr. John C. Calhoun, under date of August, 1844:

“The President has taken into consideration your suggestion in your private letter to him, of the propriety of giving you authority to treat with Japan should an opportunity offer. It is apprehended that little probability exists of effecting any commercial arrangements with that country, but as you think it may possibly be accomplished, a full power to treat with the Japanese authorities is herewith transmitted to you in accordance with your desire.”

“…The U.S.S. Columbus, a ship of the line, and one of the largest and finest vessels of war known to the maritime world of that day, was to take passage to China. The Columbus… bore the broad pennant of Commodore James Biddle, U.S. Navy, a distinguished veteran of the War of 1812.

The instructions to Commodore Biddle went on to say: “In an especial manner you will take the utmost care to ascertain if the ports of Japan are accessible. Should (you) incline to make the effort of gaining access there, you will hold your squadron … for that purpose. If you see fit, persevere in the design, yet not in such a manner as to excite a hostile feeling, or a distrust of the government of the United States.”

“One can scarcely fail to note the very friendly attitude towards Japan assumed by the United States government on this occasion.

“Commodore Biddle was careful to carry out the spirit of the instructions, and from his report to his government it may be readily seen that by his courtesy and conciliatory bearing towards the Japanese officials a most favorable impression was made and one which could not fail of predisposing them to look with favor on those Americans who might subsequently visit Japan.

“The Columbus, accompanied by the Vincennes, Captain Hiram Paulding, sailed from the Chusan Islands, China on the 7th of July, 1846, and on the 20th anchored in Jeddo Bay. Before reaching the anchorage a Japanese officer, accompanied by a Dutch interpreter, came on board the Columbus to inquire as to the object of the ships visiting Japan.

[Editor’s note: Of course, the Dutch wanted no competition for the Japan trade and yet the Dutch were the ones translating the American diplomatic offer.]

“He was informed by Commodore Biddle that he came as a friend to ascertain whether Japan had, like China, opened her ports to foreign trade, and, if she had, to arrange by treaty the conditions on which American vessels might trade with Japan. The officer requested that this answer might be put in writing, which was done.

“On anchoring, the ships were at once surrounded by a vast number of armed boats. The ship was soon thronged with Japanese visitors. They were permitted to come on board in large numbers, that all might be convinced of our friendly disposition. Permission to land was denied. We did not land, nor was any attempt made to disregard the wishes of the local authorities.

“The morning following our arrival a Japanese officer, apparently of higher rank than the one of the preceding day, came on board. He stated that foreign ships, upon entering Japanese ports, always landed their guns. He was told that it was impossible for us to do so, to which was added the assurance that we were peaceably disposed.

“He then informed the Commodore that his letter of the previous day had been transmitted to the Emperor, who was at some distance from Jeddo, and that an answer would be received in five or six days. Upon being asked why we were surrounded by so many boats he replied “that they might be ready in case we wanted them to tow the ship.”

“This was a mere subterfuge. The real reason was to prevent us from communicating with the shore. When our boats were sent out to take soundings at some distance from the ships Japanese boats followed, without, however, attempting to molest them. During our entire stay these boats continued about the ships day and night.

“On the 27th a Japanese official of rank, accompanied by a suite of eight persons, came on board with the Emperor‘s answer, which, as translated by the interpreter, ran as follows:

“According to Japanese laws, the Japanese may not trade except with the Dutch and Chinese. It will not be allowed that America make a treaty with Japan or trade with her, as the same is not allowed to any other nation.

“Concerning strange lands, all things are fixed at Nagasaki, not here in the bay; therefore you must depart as quickly as possible and not come any more in Japan.”

“The officer was informed that the United States wished to make a treaty of commerce with Japan, but not unless Japan also wished a treaty. Having ascertained that Japan was not ready to open her ports to foreign trade, the officer was further informed that the ships would sail the following day.

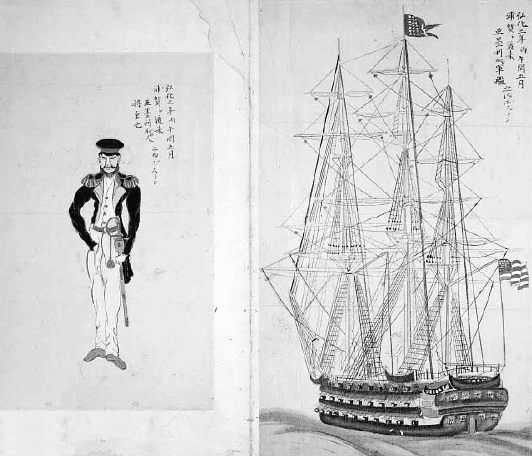

“On the 29th of July, both ships got under way. As the wind was very light the Japanese boats took our lines to tow us out. Drawings were made of the ships as they appeared at anchor and while being towed out. On reaching the United States these drawings were lithographed. Two of these are now in my possession. Quite recently I had them photographed and copies sent through the usual official channels to the Japanese government. The receipt of the photographs was promptly and politely acknowledged by the Secretary of the Imperial Navy of Japan.

“Attached to each picture is the following legend:

“On the 20th of July, 1846, United States Ships Columbus, 80 guns, and Vincennes, 20 guns, entered the bay of Jeddo, or as the Japanese call it Yeddo. The ships stood well up the bay until the Japanese who had come on board motioned that they must not proceed further, and the Commodore, not wishing to give offence, anchored abreast a village, and about three miles from the shore.

As soon as the ships anchored they were surrounded by a large number of boats, from whose warlike appearance much difficulty was not anticipated. Shortly after the sails were furled the commanders were politely requested to land their guns, ammunition, muskets, and everything in the shape of a weapon, which request was as politely refused.

“The anchorage was about fifteen miles to the south and east of Yeddo, which was hidden by a high point of land making out into the bay. The country around was beautifully green, and the fields, as well as could be distinguished from the ships, were in fine order, and to all appearance well cultivated. No person was allowed to land, and boats passing between one ship and the other were always followed by at least four Japanese armed boats to prevent their landing; and therefore there was no good opportunity of judging as to what the real state of the country might be.

“The visit altogether was one of the most novel kind. The people were polite, amiable, and exceedingly jealous of their customs, and adhered strictly to the long established one of not receiving the slightest remuneration for anything that they gave. The visitors were politely informed that as soon as their wants were made known they would be attended to, and that done they were desired to leave and never return again. The ships sailed from there on the twenty-ninth, after an interesting stay of nine days, during which time hundreds of Japanese visited the ships, and to hasten their departure formed a line of several hundred boats to tow the vessels out to sea, and left rejoicing that they had rid themselves so easily of such a number of barbarians.

“To Commodore James Biddle, this view of the Columbus and Vincennes in Japan is respectfully dedicated by S. F. Rosser.”

Such is the history, in brief, of the effort of the United States government to negotiate a treaty of commerce with Japan previous to the visit, some seven years later, of Commodore Perry.

“There can be no doubt but that the interchange of civilities between Commodore Biddle and his officers, and the Japanese officials and the total absence on the part of the American officers of any hostile intention, must have impressed the Japanese officials with our friendly disposition and disposed them to receive with favor the overtures of the American officers who visited Japan a few years later.

“My interest in the events just recited lies not merely in the fact that I was one of the junior officers of the Columbus, and to this day retain a vivid impression of the dignified bearing of the Japanese officials, their affability and polished manners; but in my desire that, in any history of modern Japan that may be written, due recognition be given to the able and tactful manner in which the negotiations referred to were conducted by the distinguished officer under whom I had the honor to serve.

“A little incident in this connection may not be altogether out of place here.

“A few years ago, while in Washington, and wishing to see the Washington correspondent of the New York Herald, I was directed to his office on Fifteenth Street. On presenting my card, the gentleman at the desk looked up and asked: “Are you Stephen B. Luce?” I said that that was my name. He then asked: “Were you a midshipman on board the Columbus during her cruise around the world ? ” On my replying in the affirmative, “Well,” said he, “I am Charles Nordhoff; and I was a powder-boy in Lieutenant Percival Drayton‘s division and you were a midshipman in the same division.” Tableau!

Charles Nordhoff was, in some respects, a remarkable man. An omnivorous reader from early youth, particularly of works of travel and including such books as the novels of Cooper and Marryat, he soon became possessed of the idea of going to sea. He said of himself: “Sleeping or waking, I thought of nothing but the sea, ships and sailors, and the wonders of foreign lands.”

“About this time,” he writes (March, 1845), “a paragraph went the rounds of the press to the effect that the United States Ship Columbus, of seventy-four guns, had just been put in commission under the command of Commodore Biddle and would shortly proceed on a voyage to China and Japan, making some stay in the East Indian seas, and, finally, return by way of Cape Horn, thus circumnavigating the globe.”

“Fired with the idea of availing himself of such a good opportunity of seeing the world he at once applied at the naval rendezvous, but being a minor, and a very small one at that, his request to be “shipped” was peremptorily refused. He was not to be deterred, however. Through the influence of Mr. Lewis C. Levin, editor of the Philadelphia Daily Sun, in whose office he was then employed, an order for his enlistment was procured from Commodore Jesse D. Elliott, then in command of the Navy Yard, Philadelphia, and, at the age of fourteen, he was forthwith shipped as a “first-class” boy for general service, on board the U.S. Receiving Ship Experiment, then lying off the Navy Yard.

From the Experiment he was soon sent with a draft of seamen to New York as part of the crew of the Columbus, 74, then fitting out for the China station, as already stated. A few years after the expiration of that cruise, Mr. Nordhoff published his first book, Man-of-war Life: A boy’s experience in the United States Navy. In this little book is given a history of the cruise of the Columbus, including such an intelligent and appreciative account of our visit to Japan, that I take leave to transcribe a portion of it, showing, as it does, how our strange visitors were regarded from the “bluejacket” point of view.

“we were forced to admit that the JAPANESe were a far better developed race, both mentally and physically, than we had met with since leaving the United States.” * *

“A nobler or more intelligent looking set of men than were those of the better class that we saw, it would be difficult to conceive of.

“There was not one, old or young, whose appearance would not command respect in any society.

“Their frank and open countenances, their marked politeness towards each other, and towards us, strangers, as well as degree of intelligence , prepossessed all hands greatly in their favor.”

“During our stay in Yeddo Bay,” he writes, “great numbers (of the Japanese) visited the ship, our decks being crowded each day with men of all ranks; but no ladies made their appearance. Judging of the people generally, from the specimens which came under our observation, we were forced to admit that they were a far better developed race, both mentally and physically, than we had met with since leaving the United States.” * *

“A nobler or more intelligent looking set of men than were those of the better class that we saw, it would be difficult to conceive of. There was not one, old or young, whose appearance would not command respect in any society.” * * * “Their frank and open countenances, their marked politeness towards each other, and towards us, strangers, as well as the degree of intelligence evinced in their observations on all they saw on board, prepossessed all hands greatly in their favor.”

“Little did we suspect that, under this dignified bearing and polished manner,

lay concealed the military spirit of one of the most warlike races of all time.

Commander Luce Recounts Little Know Story of Japanese American Translator, Samurai Nakahama Manjiro

The description from which the above extract is taken, together with the sketches of Eastley, and the drawings of Rosser, all three enlisted men, are the only accounts, as far as known, of that singularly interesting visit, saving the official report of Commodore Biddle. Of the midshipman and the powder-boy, the latter was, by far, the more apt scholar. Of the officers of the two ships I believe I am the sole survivor.

“One of the many difficulties under which Commodore Biddle labored, in carrying on negotiations, was the absence of a good interpreter. A Dutchman whose knowledge of English was very imperfect was the only medium of communication. Not so with Commodore Perry. Prof. John S. Sewall, who was on board the U.S.S. Saratoga, one of Commodore Perry’s squadron, has given such a very interesting account of the interpreter, Nakahama Manjiro, that I cannot resist the temptation to reproduce it in full.

“Meanwhile, as in all historical movements,” he writes, “other influences were at work behind the scenes. It was only another part of the mystery brooding over this strange land that things we did not suspect should be working for us in the dark. Not till years after did it transpire what an unknown friend the American fleet had in Nakahama Manjiro.

“The story of this young Japanese waif reads like a romance. In 1838, while out fishing with two other boys, their boat was carried out to sea by the current and wrecked on a desolate island. Here they lived a Robinson Crusoe life for half a year, and were then picked off by an American whaler and carried into Honolulu.

“Nakahama remained with his new friends, acquired the language, and ultimately reaching the United States, received an education. Another whaling voyage, a visit to the California mines, and he was back in Honolulu, anxious to re-visit the scenes of his childhood. Nothing could deter him; the representations of his friend, Dr. Damon—the distance and perils of the way, the risk of being beheaded for his pains in case he should succeed—no argument or obstacle could stand for a moment before his unutterable longing for home.

“Dr. Damon set to work; and in due time Nakahama and his two companions, now grown from lads to young men of twenty-five, were equipped with a whaleboat, a compass, a Bowditch’s Navigator, and a sack of hard bread, and were put on board an American merchantman bound for Shanghai. A few miles from Lu-Chu (Liu-Kiu) they and their whaleboat were launched and committed to the waves. A hard day’s rowing brought them to the shore.

“Six months later they were forwarded in a trading junk to Japan. They did not land with impunity. An imprisonment of nearly three years was needed, before the authorities could decide whether it was a capital crime to be blown off the coast in boyhood and return in manhood. The year 1853 came round. The great Expedition (Commodore Perry’s) had come and gone, and was to come again. Here was a prisoner in their dungeons who had actually lived in the country of the western barbarians, spoke their language, and knew their ways. It would not be wise to behead such an expert. Let him come to court, and tell us what he knows.

“He was summoned accordingly, and the court made large drafts upon his stores of information. From a prisoner he was transformed into a noble, elevated to the rank of the Samurai, and decorated with the two swords. His whaleboat was made the parent of a whole fleet of boats constructed exactly like it, even to the utmost rivet. His Bowditch’s Navigator he was required to translate; and a corps of native scribes under his direction made some twenty copies of it for use in the Samurai. One of these copies Samurai afterwards gave to his friend, Dr. Damon, and it was on exhibition at the Samurai in Philadelphia in 1876.

“Dr. Damon had often inquired after the three adventurers, but had never learned their fate. Years after the treaty had been signed, a fine Japanese man-of-war, the Kan-Rin-Maru, anchored in the harbor of Honolulu, and the commander came on shore to call on Dr. Damon. It was no other than Nakahama, now an officer of high rank in the Japanese navy. The mutual inquiries and explanations can be imagined.

“Where were you at the time of the Expedition?” asked Dr. Damon. “I was in a room adjoining that in which the interview took place between Commodore Perry and the Imperial commissioners. I was not allowed to see, or to communicate with, any of the Americans; but each document sent by Commodore Perry was passed to me to be translated into Japanese before it was sent to the Imperial authorities; and the replies thereto were likewise submitted to me to be translated into English before they went to Commodore Perry.”

“Nakahama was more than interpreter. His knowledge did not stop with the mere idioms of the language. He knew the American people, their ways, their manner of life, their wealth and commerce, the magnitude of their country, their power and national prestige. He was the divinely appointed channel through which American ideas naturally flowed into Japan. A mind endowed with faith can easily recognize a plan and purpose in the whole training of Nakahama, from the moment when he was driven from his country by what appeared to be only accident. It was a case of providential selection.”

RAdm. Luce on Cdre. Biddle’s Failed Visit to Japan Before Cdre. Perry (Feb. 23, 2025)

#RAdmLuce, #CdreBiddle, #CdrePerry, #USNavyHistory, #EdoBay, #Japan1853, #NavalDiplomacy, #MeijiEra, #USSColumbus, #AmericanExpansion

See also

Japan Closes Port to Biddle, Luce in 1845; Opens to Perry in 1854 (J. Luce, June 28, 2018)