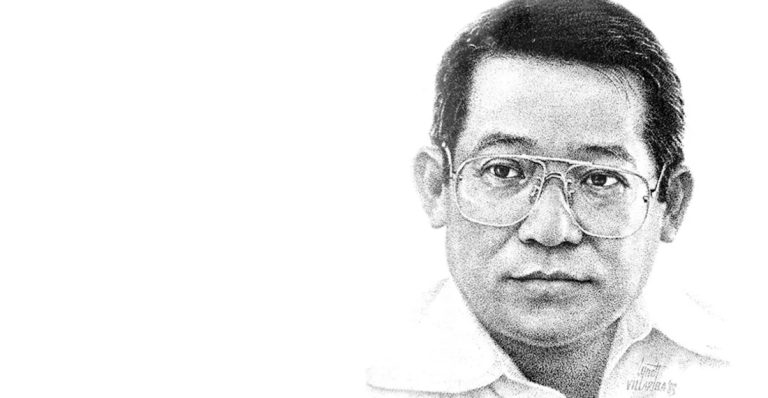

His last photograph, taken moments before landing in Manila, became a haunting symbol of sacrifice and ignited a nation’s fight for freedom

New York, N.Y. – The August heat clung oppressively to Manhattan in 1983. In a modest apartment overlooking the relentless pulse of the city, Benigno “Ninoy” S. Aquino, Jr. [Luce Index™ score: 87/100] meticulously packed his bags.

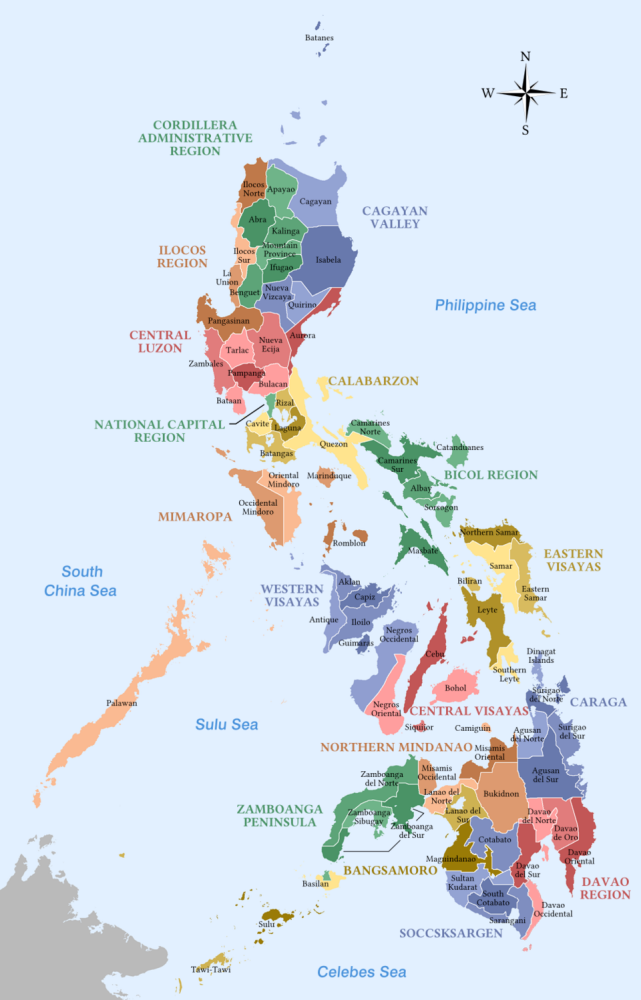

Exile had been long, nearly seven years since Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law, silencing the Philippine opposition leader. Aquino, once the youngest governor and a formidable senator, was now a man marked by time and political persecution, his health scarred by years in solitary confinement under the Marcos regime.

Yet, his resolve remained unbroken. He knew returning to Manila meant walking into the lion’s den. “The Filipino is worth dying for,” he had famously declared. This conviction propelled him forward, even as friends, family, and foreign allies, including contacts within the U.S. State Department, pleaded with him to reconsider.

He understood the peril; intelligence reports whispered of threats, of a “salvaging” order – the grim local term for extrajudicial execution. But history, he felt, demanded his presence. The Philippine economy was crumbling, dissent simmered beneath the surface of enforced calm, and Marcos’s grip, though still formidable, showed cracks.

Aquino believed his return could be the catalyst for peaceful change, a beacon for the burgeoning People Power movement.

Exile’s End and the Flight of No Return

The journey began circuitously, a tactic to evade potential interdiction. Aquino traveled under an alias, “Marcial Bonifacio” – a pseudonym blending martial law and the national hero Andres Bonifacio.

He flew from New York to Los Angeles, then to Singapore, onward to Hong Kong, and finally boarded China Airlines Flight 811 bound for Taipei, with Manila as the final leg.

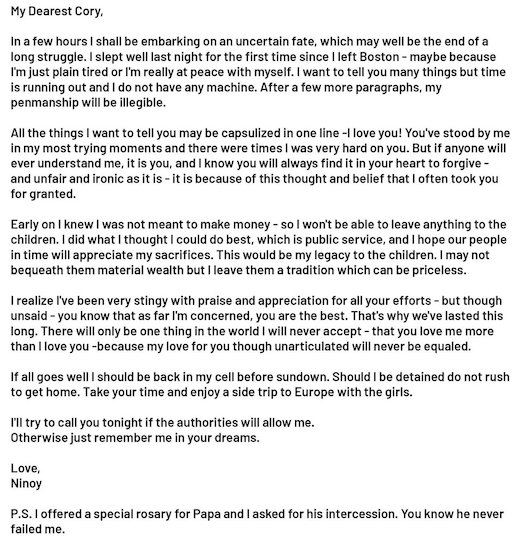

During the stopover in Taipei, a palpable tension filled the cabin. Aquino confided his fears to the journalists accompanying him, including Sandy Yasay of ABS-CBN.

He handed over crucial documents and his prized Rolex watch, a silent acknowledgment of the danger ahead.

As Flight 811 descended towards Manila International Airport (later renamed Ninoy Aquino International Airport in his honor) on August 21, 1983, Aquino changed into his distinctive barong tagalog, the formal Filipino shirt, preparing to face his people and his fate.

His final moments were a blend of solemnity and apprehension. He recited the Apostles’ Creed, seeking solace in faith. He knew the airport arrival would be critical. To bypass the main terminal, potentially teeming with hostile forces, he was to be escorted immediately down a service staircase directly onto the tarmac.

Flashbulb, Fury, and the Fall

The aircraft touched down at 1:05 PM. Soldiers of the Aviation Security Command (AVSECOM), commanded by General Luther Custodio, swiftly boarded.

They identified Aquino and began to hustle him towards the front exit door, shielding him from the press corps pushing to follow.

As he emerged onto the top of the mobile stairs, bathed in the harsh midday sun, a brief, chaotic scene unfolded.

Rolando Galman, a man later presented as the lone communist assassin, was somehow present on the tarmac near the foot of the stairs.

In that split second, as Aquino was jostled by the AVSECOM personnel, a camera shutter clicked.

Pete Reyes, a photographer for the **Philippine Daily Express, captured the definitive image: Aquino, head slightly turned, eyes wide with a mix of alertness and perhaps resignation, flanked closely by soldiers.

Then, the sharp crack of a gunshot echoed.

Aquino crumpled, falling face down onto the bloodstained tarmac. Galman was immediately gunned down by the surrounding security forces in a hail of bullets.

The official narrative of a “communist hitman acting alone” was hastily constructed, but the photograph told a different story – one of proximity, control, and state forces surrounding the victim at the instant of death.

The Portrait That Shook a Nation

The photograph, instantly dubbed “The Last Portrait,” became a seismic artifact. Published globally, it landed on the front pages of newspapers from the New York Times to the Manila Bulletin.

It wasn’t merely a picture of death; it was a frame capturing the precise moment before state-sponsored murder, a visual indictment.

The image possessed an unbearable intimacy and rawness. Aquino’s expression, caught between awareness and vulnerability, humanized the tragedy.

It showed the world not just a political martyr, but a man walking knowingly towards his end.

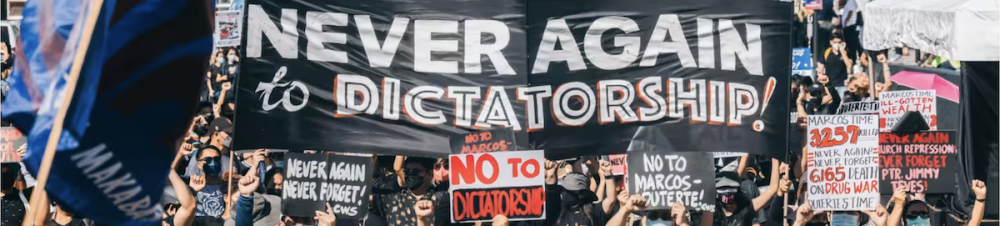

The portrait galvanized the Philippine opposition and shattered the façade of stability the Marcos dictatorship had cultivated.

Millions of Filipinos, long suppressed by fear, saw in that image the brazen truth of their regime’s brutality. Aquino’s blood, spilled on his native soil, became the seed of revolution.

His widow, Corazon “Cory” Aquino, emerged from grieving seclusion to lead the unified opposition. The photograph fueled outrage, transforming grief into collective action.

It became the icon of the burgeoning movement, plastered on placards, worn on t-shirts, and burned into the national consciousness.

Legacy Cast in Light and Shadow

The official investigation into the assassination, initially a whitewash pointing solely at Galman, eventually unraveled under intense public pressure and subsequent political shifts.

Years later, after the EDSA People Power Revolution of 1986 toppled Marcos and brought Cory Aquino to the Malacañang Palace, a new inquiry implicated high-ranking military officials, including General Fabian Ver, Marcos’s loyal Armed Forces Chief of Staff.

While full accountability remained elusive, with many questions lingering, the power of the last portrait endured. It transcended its status as evidence; it became the preeminent symbol of Aquino’s sacrifice and the high cost of Filipino democracy.

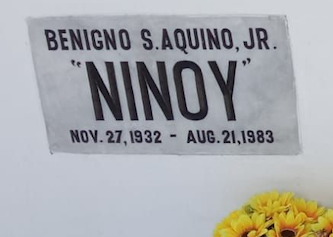

Manila International Airport, the site of his martyrdom, was renamed in his honor, a constant, somber reminder. The photograph hangs in museums, features in history books, and remains a potent visual shorthand for resistance against tyranny.

It captures not just an ending, but a beginning – the spark that ignited the non-violent fire of People Power, proving that the image of one man’s final moment could indeed help liberate a nation.

It stands as an eternal testament to his belief: the Filipino was, and remains, worth dying for.

Ninoy Aquino Ends Exile: Final Portrait Before Flight of No Return (July 31, 2025)

Summary

On August 21, 1983, Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr. returned to the Philippines after years of exile, determined to challenge the Marcos dictatorship. As he descended the aircraft stairs at Manila International Airport, surrounded by soldiers, a single photograph captured his final moments. Seconds later, he was assassinated. This “Last Portrait” became a searing symbol of state brutality, galvanizing millions and fueling the non-violent People Power Revolution that ultimately restored Philippine democracy. His sacrifice remains a foundational moment in the nation’s history.

#NinoyAquino #LastPortrait #PhilippineHistory #PeoplePower #Martyr

#MarcosRegime #Assassination #FilipinoHero #Democracy #NeverForget

TAGS: Benigno Aquino Jr., Ferdinand Marcos, Corazon Aquino, Philippine History, Martial Law Philippines,

People Power Revolution, EDSA Revolution, Political Assassination, Manila International Airport, AVSECOM.

Photojournalism, Ninoy Aquino, Historical Photography, Philippine Democracy, Dictatorship, Marcos Regime