Same-Sex Relations Decriminalized in 1871, Same-Sex Marriage Arrived in 2022; How Activism Forged Latin America’s Quiet Revolution

New York, N.Y. — The heat of a Mexico City summer still lingers in my memory—the scent of churros and exhaust fumes mixing with the electric buzz of Zona Rosa, where I wandered as a wide-eyed young man exploring a sanctuary of rainbow flags and clandestine bars.

Decades later, as a journalist and advocate, I reflect on Mexico‘s extraordinary journey: a nation that decriminalized same-sex relations before the Model-T rolled off assembly lines, yet needed until 2022 for marriage equality to sweep all of its 32 states.

This is a story of revolutionary patience, where pre-Columbian acceptance collided with colonial cruelty, and where today’s Pride parades pulse with the ghosts of activists who marched under threat of state execution.

Roots in Ancient Soil: Muxes and Colonial Crackdowns

Long before Spanish galleons arrived, Mexico’s Indigenous cultures held nuanced understandings of gender and sexuality.

Among the Zapotec people of Oaxaca, muxes—individuals assigned male at birth who embrace feminine roles—were revered as bridges between worlds, blessed with special spiritual powers.

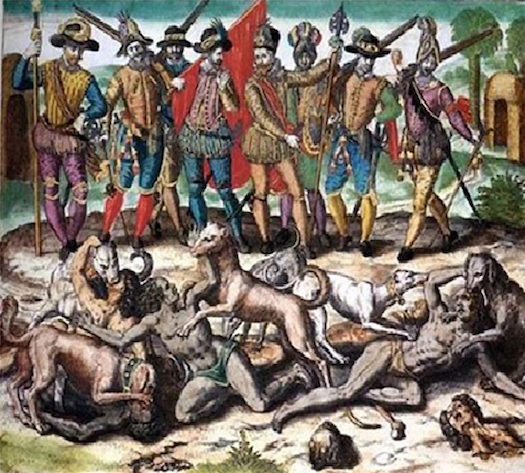

This acceptance shattered under Spanish colonialism, which imported Europe’s sodomy laws and Inquisition trials.

By the 1600s, same-sex intimacy carried death sentences, driving underground what Indigenous societies had celebrated for millennia.

The colonial legacy persisted through Mexico’s independence in 1821, but liberal reforms gradually chipped away at ecclesiastical control.

In 1871—just six years after the U.S. Civil War ended—Mexico’s Penal Code quietly removed prohibitions on consensual same-sex relations, making it one of the world’s first nations to decriminalize homosexuality.

This landmark moment occurred without fanfare, buried in broader legal modernization that few recognized as revolutionary.

From Shadows to Sunlight: The Birth of Activism

Mexico’s modern LGBTQ+ movement emerged from the upheaval of 1968, when student protests cracked open authoritarian control. In 1971, writer Carlos Monsiváis penned essays defending sexual diversity, while underground groups like Frente de Liberación Homosexual (FLH) formed in the capital’s bohemian neighborhoods. The movement’s coming-out moment arrived on July 26, 1978, when roughly 300 activists marched down Paseo de la Reforma for Mexico’s first Pride parade, chanting “¡Salir del clóset!” (Out of the closet!) as bemused onlookers gawked.

The 1980s brought both tragedy and solidarity as the AIDS epidemic devastated communities. Groups like Círculo Cultural Gay transformed from social clubs into advocacy organizations, demanding healthcare access and anti-discrimination protections. I witnessed this evolution firsthand during my visits to Zona Rosa, where the district’s cabaret culture provided camouflaged community spaces. Behind the sequins and spotlight of venues like El Taller lay networks of mutual aid that sustained a generation through the plague years.

Legal Victories and Constitutional Battles

Mexico City blazed the trail toward marriage equality in 2009, when the capital’s assembly approved same-sex unions over fierce Catholic Church opposition. The decision triggered a constitutional crisis as conservative states challenged the law’s validity. In 2015, the Supreme Court issued a landmark ruling declaring marriage bans unconstitutional, though implementation varied wildly across states. Some embraced change immediately; others required individual lawsuits that stretched for years.

The breakthrough came in 2022 when Tamaulipas became the final state to legalize same-sex marriage, completing a 13-year struggle for nationwide equality. This victory coincided with broader LGBTQ+ advances, including gender identity recognition laws and anti-discrimination protections in employment and education. Mexico now ranks among Latin America’s most progressive nations on sexual and gender diversity—a remarkable transformation for a country where machismo culture runs deep.

Pride in the Present: Reflections from Zona Rosa

Walking through Zona Rosa today, I’m struck by how far Mexico has traveled since my first tentative exploration of its gay neighborhoods. The district still pulses with rainbow energy, but the furtive glances have given way to open celebration. Mexico City’s annual Pride march now draws over 100,000 participants, transforming the Zócalo into a carnival of visibility that would have been unimaginable during the underground years.

Yet challenges persist. Transgender Mexicans face alarming violence rates, with advocacy groups documenting hundreds of murders in recent years. As all over the world, rural areas lag behind urban centers in acceptance, and religious conservatism still wields political influence. The muxe communities of Oaxaca, meanwhile, navigate between traditional respect and modern prejudice, their ancient acceptance threatened by imported homophobia.

Mexico’s journey from colonial persecution to constitutional equality spans centuries, but its lessons resonate globally. Progress rarely follows straight lines—it requires the patient accumulation of small victories, the courage of activists willing to march when marching meant arrest, and the gradual erosion of prejudice through visibility and persistence. As I learned wandering those Mexico City streets decades ago, sometimes revolution begins with simply existing in public, refusing the shadows others would impose.

Mexico’s Road to Equality: From Colonial Laws to Rainbow Flags (June 21, 2025)

75-Word Summary

Mexico pioneered same-sex decriminalization in 1871 but needed 151 years to achieve marriage equality. From Indigenous muxe acceptance through Spanish persecution to modern Pride parades, this journey reflects centuries of struggle. Zona Rosa district symbolizes transformation from underground refuge to open celebration, though transgender violence and rural prejudice persist across this Latin American leader.