THE PRESS LAUGHED AT HITLER. THE WORLD STOPPED LAUGHING

New York, N.Y. — In March 1933, The Chicago Tribune ran a headline declaring Adolf Hitler a “ridiculous little man” whose “frothing speeches” would soon make him a “footnote.”

Other outlets agreed: The Manchester Guardian likened him to a “comic opera villain,” while The New York Times dismissed his anti-Semitic rants as “hysterical nonsense” too absurd to take seriously.

Yet within a decade, the man the press reduced to a punchline had plunged the world into war and genocide. How did journalism’s early dismissal of Hitler fail so catastrophically—and what lessons does it hold today?

The ‘Little Man’ Narrative

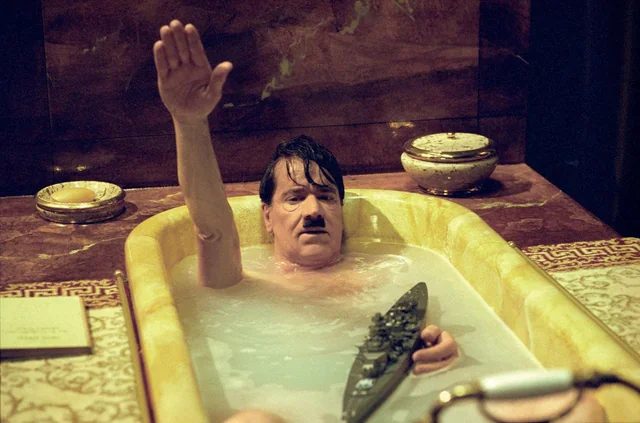

Historical archives reveal a striking pattern in 1930s coverage. Hitler was routinely mocked for his appearance, voice, and perceived incompetence. A 1931 Time magazine profile described him as a “housepainter” with a “Charlie Chaplin mustache” and “wild gesticulations.”

French and British cartoons depicted him as a squawking clown or unhinged toddler. Even after his 1933 appointment as Chancellor, The Washington Post assured readers his government would collapse within months, calling him a “temporary nuisance.”

This framing, historians argue, stemmed from two biases.

First, Western journalists struggled to reconcile Hitler’s vulgarity with Germany’s reputation as a cultured nation. “They assumed the German people would never follow someone so crude,” says Dr. Clara Velly, a political historian at Deltant University.

Second, satire was a default tool for discrediting fascism. “Laughter was seen as a weapon against extremism. But it blinded them to the structural forces enabling Hitler.”

Missed Signals in Plain Sight

While journalists ridiculed Hitler’s persona, they underreported his methodical consolidation of power. Few outlets deeply analyzed the Nazi Party’s grassroots networks, paramilitary intimidation, or exploitation of economic despair post-1929.

The New York Times did note Hitler’s “eerie hold” on crowds but framed it as a curiosity rather than a strategic asset. Meanwhile, antisemitic laws were often buried in briefs or described as “eccentricities.”

Critically, the press underestimated Hitler’s intent. His manifesto Mein Kampf—openly detailing plans for conquest and racial purification—was dismissed as “mad ramblings.”

When Germany reoccupied the Rhineland in 1936, violating the Treaty of Versailles, The Times of London editorialized that Hitler was “bluffing for attention.”

By the time journalists began taking him seriously, the Nazi regime had dismantled democratic institutions and silenced dissent.

The Cost of Underestimating Hate

The consequences of this oversight were dire. By reducing Hitler to a joke, the media inadvertently normalized his early transgressions.

Diplomat George Messersmith warned in 1933 that Hitler’s “fanaticism” posed an existential threat, but his memos were overshadowed by sensational headlines about the führer’s “quirks.” Similarly, Jewish refugees’ accounts of persecution were often relegated to back pages, deemed less newsworthy than Hitler’s theatrical rallies.

“Ridicule can disarm fear, but it also breeds complacency,” says Jim Luce of Luce Family Charities. “When you paint a dictator as a clown, the public assumes he’ll implode. But that ignores how effectively authoritarians exploit crises.”

Modern Parallels

Scholars draw connections to contemporary media handling of demagogues. “The ‘little man’ trope resurfaces whenever a polarizing figure seems too absurd to be dangerous,” notes Luce. “But Hitler’s rise proves charisma isn’t necessary—what matters is leveraging resentment and institutional decay.”

Luce adds that modern outlets risk repeating history by prioritizing viral mockery over investigative rigor: “Clickbait headlines about a leader’s ‘meltdown’ don’t explain how they’re eroding checks and balances.”

Luce described Donald Trump as a Fascist when Trump descended the Trump Tower escalator to announce his bid for the president presidency in June 2015. “I was nervous to be so strong in my criticism of him and was relived when the BBC came out a few months later with the same description,” Luce states. The BBC used this term in December 2015.

Hitler’s ascent remains a case study in the limits of journalistic ridicule.

While the press accurately noted his pettiness and instability, it mistook these traits for weakness rather than recognizing their weaponization. As today’s democracies confront resurgent authoritarianism, the 1930s remind us that laughter alone cannot defeat tyranny—it must be met with unflinching scrutiny.

Journalists Called Hitler a Joke. The World Paid the Price (March 25, 2025)