I met Jean-Michel briefly at a party at Andy Warhol’s Factory. I found him to be aloof if not rude – the price of fame?

New York, N.Y. — Jean-Michel Basquiat, a defining figure of the 1980s New York art scene, used his neo-expressionist paintings to confront systemic racism with unflinching clarity. His work, characterized by raw energy, vibrant colors, and layered symbolism, served as both artistic expression and social critique. Basquiat’s art didn’t just reflect the world around him—it challenged it, exposing the deep-rooted racial inequalities that shaped American society.

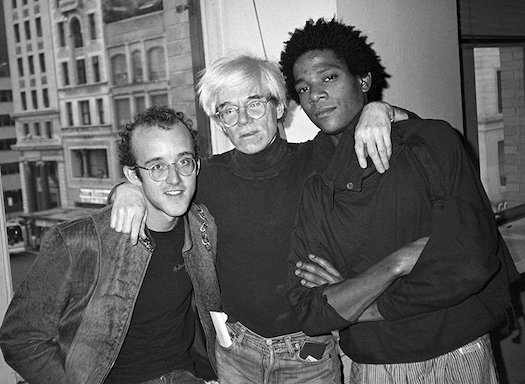

I lived in the East Village in the early 1980’s and met Jean-Michel briefly at a party at Andy Warhol‘s Factory. I found him to be aloof if not rude. I thought maybe because I was white, but then Andy–also white–was his mentor, so that didn’t make sense.

But when you are a famous genius, I guess you can be whatever you wish… Keith Haring and Madonna were around the East Village then as well.

I often saw Keith doodling on the walls of the Astor Place subway station, while Madona and her dancers would circle the neighborhood in a limousine.

Born in Brooklyn in 1960 to Haitian and Puerto Rican parents, Basquiat’s multicultural background informed his perspective. He rose from a graffiti artist, tagging New York City streets under the pseudonym SAMO, to an internationally celebrated painter.

His meteoric ascent in the predominantly white art world was both a triumph and a paradox, as he navigated spaces often hostile to Black voices. This tension fueled his work, which tackled themes of racial injustice, identity, and power dynamics.

One of Basquiat’s most poignant works, Irony of a Negro Policeman (1981), encapsulates his critique of systemic racism. The painting depicts a Black police officer in a stark, almost cartoonish style, surrounded by chaotic lines and fragmented imagery. The title alone underscores the contradiction: a Black man enforcing a system that historically oppressed his community. Basquiat’s use of text and symbols, like crowns and skeletal forms, further amplified the painting’s commentary on authority and marginalization.

His works often blended historical references with contemporary issues.

In Untitled (History of the Black People) (1983), Basquiat reimagined the African diaspora, drawing on Egyptian iconography and slave trade imagery to trace a narrative of exploitation and resilience. The painting’s fragmented composition mirrors the disjointed experience of Black identity in a racially divided society. By juxtaposing ancient motifs with modern struggles, Basquiat highlighted the enduring impact of systemic racism across centuries.

Basquiat’s style—rooted in graffiti’s spontaneity and neo-expressionism’s emotional intensity—gave his social critiques visceral power. His canvases, filled with scribbled text, distorted figures, and bold colors, demanded attention. Pieces like Defacement (The Death of Michael Stewart) (1983) directly addressed racial violence. Inspired by the death of a young Black artist at the hands of police, the painting features two officers looming over a skeletal figure, a raw indictment of police brutality and institutional racism.

The art world’s reception of Basquiat was complex. While collectors and galleries celebrated his talent, some critics dismissed his work as primitive or overly political. This criticism often reflected the very biases Basquiat sought to expose. His ability to infiltrate elite spaces while remaining an outsider gave his art a unique vantage point, amplifying its critique of systemic inequities.

Basquiat’s influence extended beyond the canvas.

His collaborations with Andy Warhol and his friendships with figures like Madonna and Debbie Harry bridged the art world and popular culture. Yet, he remained acutely aware of his position as a Black artist in a white-dominated industry. His paintings often included references to commodification, such as price tags or brand logos, critiquing how Black bodies and culture were exploited.

Today, Basquiat’s legacy resonates in museums, galleries, and public discourse.

Major exhibitions, like the 2017 retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum, have reframed his work as a vital contribution to conversations on race. His paintings fetch millions at auctions, with Untitled (1982) selling for $110.5 million in 2017, a testament to his enduring impact. Yet, his art’s value lies not in its price but in its ability to provoke and educate.

Scholars and curators continue to unpack Basquiat’s symbolism.

His use of crowns, for instance, is widely interpreted as a reclaiming of dignity for Black figures, from jazz musicians to everyday people. His work also draws parallels with contemporary movements like Black Lives Matter, which echo his calls for racial justice. As curator Dieter Buchhart noted, “Basquiat’s art is a mirror held up to society, forcing us to confront uncomfortable truths.”

Basquiat’s life was tragically short—he died of a drug overdose in 1988 at age 27—but his impact endures. His paintings remain a powerful lens through which to view systemic racism, blending beauty with brutal honesty. From New York’s subway walls to the world’s most prestigious galleries, Basquiat’s voice continues to challenge, inspire, and demand change, cementing his place as one of the 20th century’s most visionary artists.

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Art Explored Systemic Racism (April 27, 2025)