Landscapes from the “Fifty-three Stations” Series Reveal Edo Japan’s Soul Through Masterful Ukiyo-e Storytelling

New York, N.Y.—In 1842, as the Edo period neared its twilight, Utagawa Hiroshige crafted Hara—No. 14, a serene vista from his legendary series Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido. Five years later, Sakanoshita—No. 49 emerged—a dramatic mountain pass echoing with travelers’ footsteps.

These woodblock prints, housed at the Art Institute of Chicago, transcend mere documentation of the Tokaido highway. They immortalize a poetic dialogue between land and life, inviting modern viewers into 19th-century Japan’s spiritual and social rhythms.

The Tokaido: Journey Through a Transforming Nation

The Tokaido, stretching 319 miles between Edo (Tokyo) and Kyoto, pulsed as Japan’s cultural and economic lifeline. By Hiroshige’s era, over 300 years of peace under the Tokugawa shogunate had birthed a travel boom. Pilgrims, merchants, and daimyō (feudal lords) traversed its 53 post stations, fueling demand for souvenirs like Hiroshige’s prints.

Unlike contemporaries fixated on kabuki actors or courtesans, Hiroshige elevated landscapes to emotional narratives. His Reisho Tokaido sub-series—distinguished by vertical formats and restrained palettes—balanced realism with lyricism, mirroring ukiyo-e’s (“pictures of the floating world”) ethos: beauty in transience.

Hara: Station 14’s Sublime Serenity

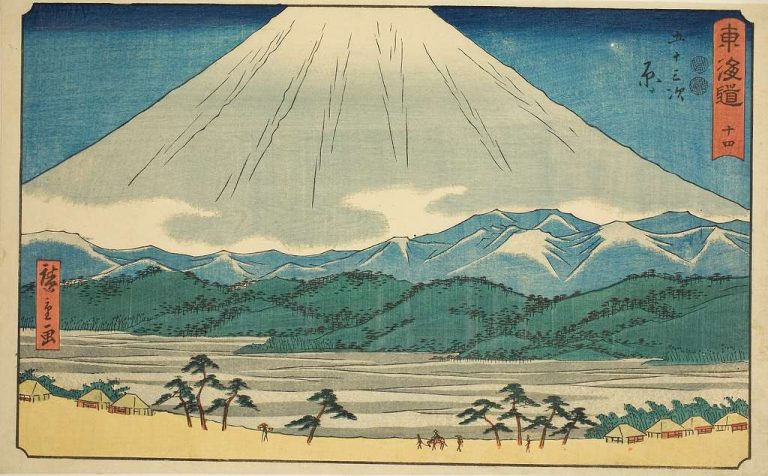

Hara—No. 14 (1842) captures travelers resting near reed-thatched huts, dwarfed by Mount Fuji’s snow-capped cone. Hiroshige renders the volcano in soft grays and blues, its slopes echoing the thatched roofs’ curves. Three foreground figures—back turned, faces hidden—evoke anonymity, emphasizing collective experience over individualism.

A lone pine tree anchors the composition, symbolizing endurance. The scene’s quiet power lies in its spatial harmony: human structures nestle like natural extensions of the land. As art historian Timothy Clark notes, Hiroshige’s genius was “making the ordinary luminous”—here, a roadside pause becomes meditation.

Sakanoshita: Station 49’s Thrilling Ascent

Contrasting Hara’s tranquility, Sakanoshita—No. 49 (c. 1847–1852) thrusts viewers into a vertiginous climb. Travelers ascend a steep path flanked by jagged cliffs; mist swallows the valley below. Hiroshige employs bokashi (gradated ink) to heighten atmospheric depth, while vermilion accents on robes pop against mossy greens.

The perilous terrain underscores the Tokaido’s physical challenges, yet camaraderie emerges: a porter steadies a palanquin, and two figures converse mid-slope. This print exemplifies Hiroshige’s skill in compressing epic journeys into intimate vignettes—where geology and grit intertwine.

Enduring Echoes: From Edo to Van Gogh

Hiroshige’s death in 1858 coincided with Japan’s opening to the West, catapulting his work to global acclaim. Vincent van Gogh copied Hiroshige prints meticulously, praising his “astounding” use of color. The Art Institute of Chicago’s 2018 exhibition highlighted this cross-cultural resonance, displaying Hara and Sakanoshita alongside Western artists they inspired.

Beyond aesthetics, Hiroshige’s focus on communal harmony and nature’s sanctity feels strikingly modern. As climate crises mount, his vision—of humans as humble participants in vast ecosystems—resonates as both balm and blueprint.

Summary for Audio

Explore Hiroshige’s iconic Tokaido woodblock prints at the Art Institute of Chicago. “Hara—No. 14” reveals Mount Fuji’s tranquil majesty, while “Sakanoshita—No. 49” captures travelers scaling perilous cliffs. These 19th-century masterpieces blend nature, humanity, and artistry, reflecting Edo Japan’s soul and influencing giants like Van Gogh. Discover why they remain timeless meditations on journey and belonging.

Ukiyo-e Master Hiroshige at Art Institute of Chicago (June 26, 2018; republished June 20, 2025)