What began as a fight for independence turned into a bloody guerrilla struggle, leaving tens of thousands dead and a legacy of trauma.

New York, N.Y. — On February 4, 1899, just months after the Treaty of Paris (1898) ended the Spanish-American War, U.S. sentries near Manila fired on Filipino patrols.

This skirmish ignited the Philippine-American War—a conflict Washington initially dubbed an “insurrection” but historians now recognize as a brutal colonial conquest. Filipino forces under Emilio Aguinaldo, who had declared independence months earlier, faced an industrialized U.S. military determined to assert control over the archipelago.

What followed was a three-year nightmare of scorched-earth campaigns, concentration camps,

and systemic atrocities that claimed over 200,000 Filipino lives and 4,200 American soldiers.

Collision of Imperial Ambitions and Nationalist Aspirations

The war’s roots lay in the Spanish-American War, where Filipino revolutionaries allied with the U.S. to oust Spain.

When the Treaty of Paris (1898) transferred the Philippines to American control for $20 million, Emilio Aguinaldo refused to surrender sovereignty. U.S.

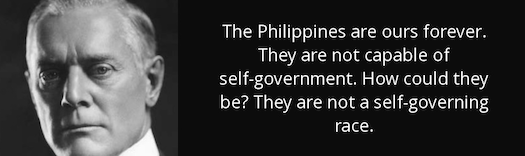

President William McKinley justified annexation through paternalistic rhetoric, calling Filipinos “unfit for self-government.”

Early conventional battles saw U.S. troops exploit technological superiority, crushing Aguinaldo’s regular army by November 1899. Yet this was merely the prelude to a deadlier phase.

Guerrilla Warfare and the Descent into Barbarity

As Filipino forces splintered into decentralized guerrilla units, the U.S. Army, under generals like Arthur MacArthur, adopted ruthless counterinsurgency tactics.

Villages suspected of aiding rebels were burned; crops and livestock destroyed in scorched-earth campaigns. Civilians were forcibly relocated into concentration camps—euphemistically termed “protected zones”—where overcrowding and disease killed thousands.

A U.S. infantryman wrote home in 1900: “We kill every native in sight… It’s no more than you would do to a pack of mad dogs.”

Atrocities and the Ethics of Empire

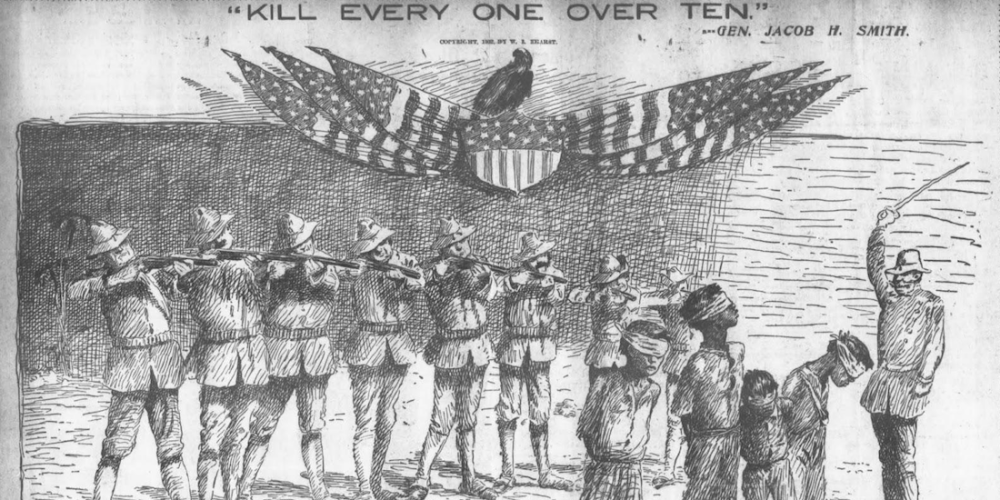

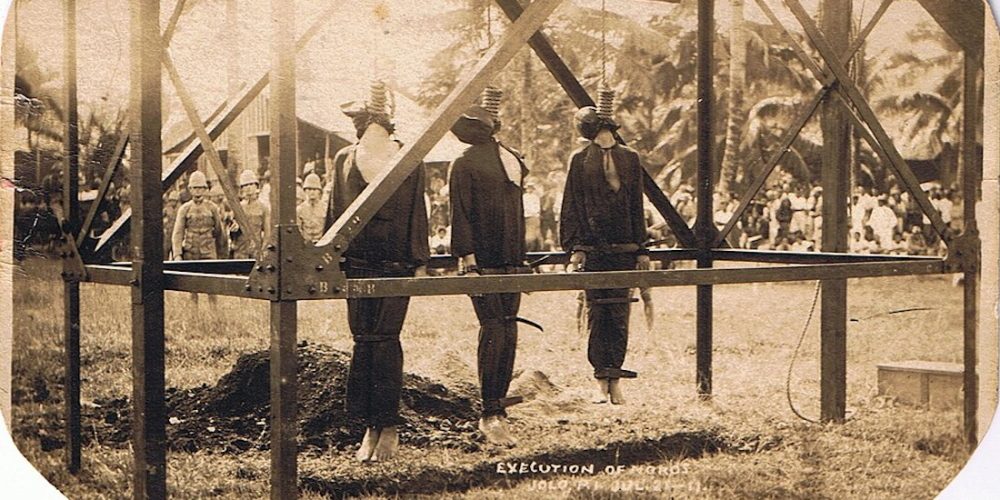

Documented massacres stained both sides, but U.S. actions drew sharp condemnation. In 1901, retaliating for an ambush that killed 48 soldiers, General Jacob H. Smith ordered troops to turn Samar into a “howling wilderness,” instructing, “Kill everyone over ten.”

The Balangiga massacre and Moro Crater massacre epitomized the dehumanizing violence. Waterboarding, called the “water cure,” was routinely used to extract intelligence. Senator George Frisbie Hoar denounced these acts as “worse than savagery,” while Mark Twain penned scathing anti-imperialist essays.

Legacy: Erasure and Enduring Scars

The war formally ended on July 4, 1902, though resistance persisted for years. The U.S. established a colonial administration under William Howard Taft, promising “benevolent assimilation.”

Yet infrastructure built under American rule—schools, roads, hospitals—could not mask the trauma. Filipino veterans were denied pensions; history textbooks minimized the conflict.

Today, mass graves still surface during construction in Luzon. As historian Reynaldo Ileto notes, the war birthed “a nationalism forged in shared suffering”—a wound that shaped the Philippines’ fraught relationship with its former colonizer.

Forgotten Conflict: The Brutal Philippine-American War of 1899-1902 (August 1, 2025)

Summary: Silenced Echoes

The Philippine-American War (1899-1902) remains a footnote in U.S. memory but a foundational trauma for Filipinos. Triggered by America’s imperial ambitions after defeating Spain, it devolved into asymmetric warfare marked by massacres, torture, and civilian internment. Over 200,000 Filipinos and 4,200 U.S. soldiers died. This summary explores how the conflict’s brutality foreshadowed 20th-century counterinsurgencies and why its legacy still resonates.

#PhilippineAmericanWar #MilitaryHistory #WarAtrocities

#Colonialism #GuerrillaWarfare #USHistory #ForgottenWars

TAGS: Philippine-American War, U.S. Imperialism, Guerrilla Warfare, War Crimes,

Military History, Colonial Atrocities, Emilio Aguinaldo, Spanish-American War