New Democratic language memo says words like “Latinx” and “birthing person” risk reinforcing perceptions of elitism and division

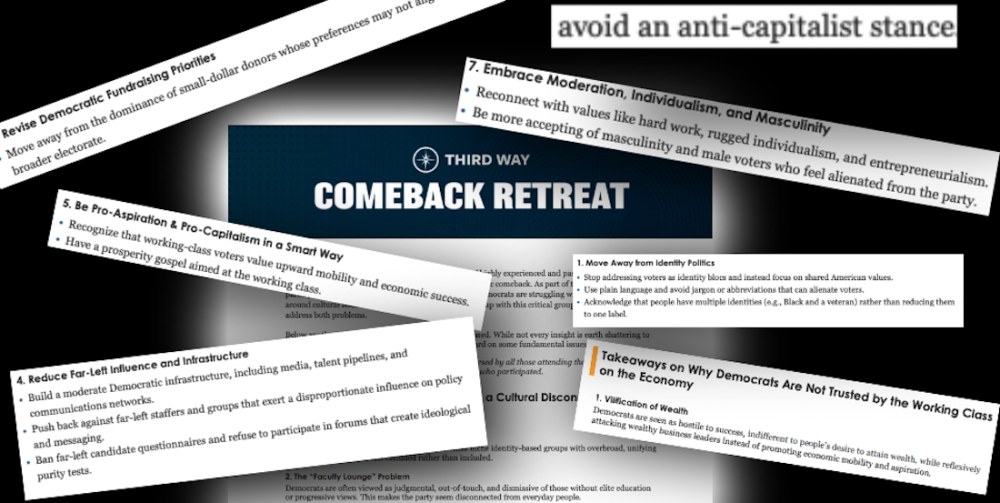

New York, N.Y. — As Democrats regroup to prevent a political setback in 2026 and beyond, a provocative internal memo from the so-called “centrist” group Third Way, funded by American corporate interests, has sparked discussion, frustration, and reflection across progressive circles.

The document, titled Was It Something I Said?, argues that the party’s reliance on academic, activist, and politically correct terms is doing more harm than good when it comes to building bridges with the very voters Democrats most need to win over.

The 10-page memo outlines phrases and concepts that have gained traction in policy circles, activist communities, and universities—yet repel many working- and middle-class Americans who perceive them as elitist, condescending, or needlessly complex.

From the now-infamous “birthing person” to jargon-heavy terms like “systemic oppression” or “stakeholders,” the memo points out that Democrats risk losing voters not because of their policies, but because of how they talk about them.

At stake, Third Way argues, is not just messaging but the ability to stop Donald Trump [Luce Index™ score: 35/100] and the broader MAGA movement from returning to power.

“When policymakers are public-facing, the language we use must invite, not repel; start a conversation, not end it,” the memo warns.

When Language Creates Barriers, Not Bridges

For a party that brands itself as the voice of inclusion, the findings are stark. According to Third Way, words designed to be considerate, nuanced, or theoretically precise often accomplish the opposite. Instead of expanding the conversation, they can shut it down.

The memo divides problematic language into six categories: therapy-speak, seminar room language, organizer jargon, gender and orientation correctness, shifting racial constructs, and crime framing. In each instance, the criticism is similar: the terms may satisfy highly engaged activists or advocacy groups but alienate the vast majority of voters who find them confusing, elitist, or scolding.

For example, therapy-inspired language like “microaggression,” “triggering,” or “safe space” may resonate in academic or activist discussions but tend to backfire in everyday political conversation. Phrases such as “justice-involved” used in place of “formerly incarcerated person” leave many feeling that the plight of victims is minimized.

“The problem is not the commitment to equity and empathy,” says Maria Lopez, a communications consultant who has advised progressive groups nationwide. “It’s that the movement sometimes chooses phrasing that signals belonging to an inside club rather than talking with everyday voters in plain language. That’s exactly when people tune out.”

Choosing Words Without Abandoning Values

At its core, the memo is not arguing for Democrats to abandon their values. Indeed, the report is careful to note that fighting bigotry, protecting LGBTQ+ rights, and addressing racism remain fundamental commitments. The issue is not what Democrats believe, but how they express it.

The authors acknowledge that much of the controversial terminology has been driven into political discourse by advocacy groups or younger progressives who view the changes as an act of respect and recognition. For example, replacing “homeless” with “the unhoused” is meant to center humanity, not reduce it. But as Third Way warns, intent and impact often collide when well-meaning shifts in wording are perceived as elitist linguistic policing.

That tension is hardly new. Democrats have wrestled with language debates since the fight over “welfare queen” stereotypes in the 1980s and right through to today’s arguments about whether to say “defund the police.” But as the memo emphasizes, the country’s current political polarization makes these choices significantly more consequential.

In short: Democrats may lose fewer votes over big, structural policies than over words that strike Americans as scolding or exclusionary.

Language Beyond the Memo: Striking a Balance

Not all progressive communicators are prepared to jettison newer terminology. Many activists argue that inclusive words—though initially unfamiliar—eventually normalize, helping society evolve toward greater humanity and acceptance. Moreover, they contend that certain terms have replaced outright offensive ones, and dropping them would constitute regression.

Take gendered job titles, for instance. Using firefighter instead of “fireman” or mail carrier instead of “postman” reflects an intentional effort to avoid unnecessary gendering. Similarly, calling someone a person living with a disability rather than a “handicapped person” helps place emphasis on the person, not the condition. Other shifts, such as older adult instead of “senior citizen,” or custodian over “janitor,” aim to neutralize stereotypes.

“Respectful terminology doesn’t have to be alienating,” explains Alan Wright, a sociolinguist at Columbia University. “The key is balance: language should show dignity without sounding contrived. You don’t need to embrace every advocacy-driven neologism, but you also don’t have to stick with words that carry bias or stigma.”

The Political Reality: Voters Want Clarity

What studies repeatedly show is that voters distrust what they don’t understand. According to Third Way, focus groups reveal that respondents often recoil when confronted with terms such as “Latinx” or “intersectionality.” Even if the ideas themselves have merit, the vocabulary can trigger suspicion. One participant in a recent focus group reportedly said, “If I don’t know what it means, I think they’re hiding something.”

That distrust amplifies cultural anxieties. In an age where people fear cancellation or public shaming for using the “wrong” terminology, many simply withdraw from political conversation altogether. That silence, the memo argues, benefits Trump and the MAGA movement, who then frame Democrats as elitist out-of-touch scolds.

The result? A political communications paradox. Democrats risk alienating not because of their policies on healthcare, wages, or climate change but because of their insistence on what some voters see as opaque or pedantic phrasing.

Looking Forward: Will Democrats Heed This Advice?

The ultimate question is whether the Democratic Party, broadly defined, will adjust its messaging in time for the next cycle. Party strategists are aware that every percentage point matters in swing districts across states like Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Arizona, and Georgia. Losing persuadable voters over terminology rather than policy could prove fatal in races decided by razor-thin margins.

Yet the tension remains. For progressives, the call to simplify language can sound like an invitation to capitulate, erasing years of effort to introduce more humane, accurate, and inclusive terms. For moderates, it is about pragmatism: clear, accessible words ensure the party continues to resonate with the broad coalition needed to stop Trump.

As one strategist summarized, “We’re not saying never use these words. But if saying them makes voters feel excluded, then we’re losing the argument before it even begins.”

Language as Strategy, Not Slogan

In an increasingly polarized America, language is not just vocabulary—it is political strategy.

The Third Way memo makes clear that Democrats have the policies and moral commitments to defeat MAGA extremism, but may fall short if voters perceive them as more concerned with linguistic correctness than with real-life struggles at the kitchen table.

The path forward may rely on what Democrats have long excelled at in theory but struggled with in practice—communicating values in ways that reflect authenticity, accessibility, and humanity.

As the memo bluntly concludes, “Communicating in authentic ways that welcome rather than drive voters away would be a good start.”

Summary

Democrats are navigating a political messaging crisis, warns a new memo from centrist group Third Way. While their values remain strong, their reliance on jargon and activist-driven language risks alienating everyday voters. Terms like “Latinx,” “birthing person,” and “intersectionality” may signal inclusivity to some but come across as elitist and confusing to many. The takeaway: Democrats must speak in accessible, authentic language if they hope to beat Donald Trump and MAGA in upcoming elections.

Democrats Warned Alienating Voters With Elitist Language Choices (Aug. 23, 2025)