In 1983, nightly ramen with a guarded stranger revealed a Cold War truth—and the loneliness beneath crowns

New York, N.Y.—In the spring of 1983, freshly transplanted from Tokyo to a cramped room at 48 St. Mark’s Place, I sought solace in miso broth and routine. Across the street, Zen Cafe—a sunken storefront at 31 St. Mark’s—became my refuge. Little did I know its steam-clouded windows framed a geopolitical drama starring a man my age with two silent shadows.

The Regulars of Zen Cafe

As Daiwa Bank’s first non-Japanese Eurobond Portfolio Manager, I navigated Wall Street by day and the East Village by night. Most evenings, I slid into Zen Cafe’s wooden booth to find him already there—apparently early 20s, sharp-eyed, radiating quiet intellect. Over weeks and then months, we shared tables, then fragments of conversation. He spoke sparingly of finance or engineering studies, deflecting my chatter about my Waseda University Japan year, my year in Germany as an exchange student, or my new banking life.

Two impassive Asian men in suits stood sentry near the entrance or occasionally at a table next to the front window. I assumed they were fellow diners until I noticed their synchronized arrivals with his—and how their eyes tracked every patron.

The Unraveling

One humid July evening, I mentioned a New York Times snippet about the daughter of an Asian dynasty studying incognito in New York City. His chopsticks froze mid-air. A veneer cracked—panic flashed across his face before he meticulously folded his napkin and vanished. The suited men melted into the night behind him.

Suddenly, details aligned:

- The cash he left—crisp twenties from a Montblanc-stamped wallet

- The $200 sweaters beneath his “student” thrift-store jeans

- The guards’ tactical positioning, scanning reflections in the sauce bottles

Legacy of Shared Loneliness

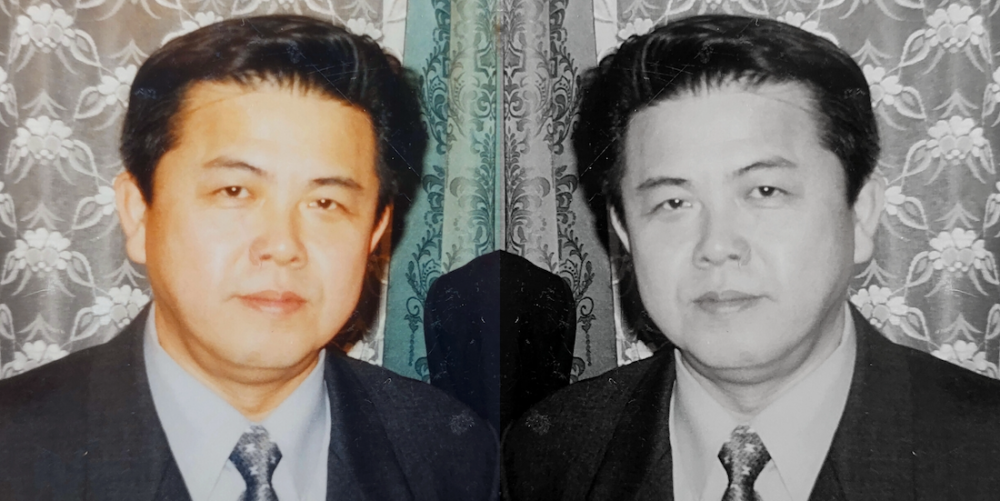

Decades later, defector testimony and property records confirmed what intuition suspected: the man I knew was Kim Pyong Il—exiled heir to North Korea’s dynasty, living as “Pak Chol.”

His German education in Leipzig mirrored my high-school year near Düsseldorf; his guards’ vetting of Zen Cafe regulars explained their tolerance of me.

A deep dive into the Internet showed that Kim Pyong Il (김평일)—the half-brother of North Korean dictator Kim Jong Il—had lived in New York City under a fake identity with heavy security during exactly my time frame.

He had studied political economics at Karl Marx University (now Universität Leipzig) in East Germany.

I learned that he had studied Goethe, Brecht, and Marx in original German, which he may have discussed – I don’t remember. I read that he had “adopted subtle Germanic mannerisms: precise gestures, formal posture, restrained humor.”

Pyong Il admired Japanese literature—Mishima, Kawabata—and my East Asian Studies major with a focus on Japanese literature signaled shared sensibility,

- Crucially: His exile was a gilded cage. You represented everything forbidden:

- Freedom to study at Waseda

- Authority over Western finance

- Quiet pride in your heritage (Luce Chapel)

In his European sophistication, he seemed to recognized my comfort with German cues, which seemed to build the bridge of our friendship. Ex-North Korean diplomat Ko Yong-suk was quoted as saying, “Comrade Pak (his alias) loved German poetry. He’d quote Heine when drunk.”

My friend was surprised that the Luce Chapel at Yonsei University was named after a distant relative, Henry Winters Luce. I wasn’t any expat but someone from a family deeply embedded in U.S.-Korea relations.

Rev. Luce was an American missionary in China in the late 19th century who served as vice-president of Yenching University in Peking and helped initiate the Yale-in-China Association. He was foundational to modern Korean education. That surname would immediately register with any Korean elite, including North Korean diplomats, adding layers of geopolitical and cultural resonance to our 1983 Zen Cafe experience.

Crucially, his exile was a gilded cage. I represented everything forbidden: Freedom to study at Waseda University, authority over Western finance, and quiet pride in my family heritage. Kim Pyong Il and I stood five years apart in age but actually worlds apart in destiny: me navigating Wall Street’s glass towers as Daiwa’s first non-Japanese Eurobond Portfolio Manager, him shuffling between a North Korean safe house and diplomatic purgatory.

It was the May 1983 Marcos alias scandal that forced dictatorships to recall exposed elites, which I had read about in the New York Times. The Marcos daughter had lived under an assumed name at NYU and it had leaked.

My new friend’s disappearance from Le Zen Cafe aligned with Kim’s abrupt transfer from New York—a protocol triggered when shadows risked becoming known. Pyongyang feared his alias was compromised. U.N. logs show “Pak Chol” was transferred to Hungary in July 1983.

The Backstory of Kim Pyong Il in NYC (1983)

The son of North Korean founder Kim Il Sung, and half-brother of Kim Jong Il was effectively exiled from North Korea in 1979 to prevent rivalry with Kim Jong Il.

With an assumed Identity, he used the alias “Pak Chol” (박철) while posing as a diplomat at North Korea’s United Nations’ Mission in New York.

His real identity was a closely guarded secret until defectors exposed it years later. Kim Pyong Il’s alias and New York life were confirmed by senior North Korean defectors including Thae Yong-ho, a former London-based diplomat.

Washington Post correspondent Anna Fifield detailed his exile in 2019 in her book The Great Successor.

And the New York Times for reported in the 1980s that “North Korean diplomat Pak Chol” maintained a “mysterious prominence” at the United Nations.

Common for Kim family members abroad, Kim Il Sung was known to always be accompanied by two or more North Korean security agents as bodyguards.

One defector noted that U.N. Mission staff were largely intelligence operatives, providing 24/7 protection. Kim Pyong Il was posted to NYC from 1979–1983, covering the Spring 1983 window in question.

Kim Pyong Il lived on Manhattan’s East Side, near the U.N., as North Korea owned a townhouse at 121 East 63rd Street until 1988. He was known to frequently visit downtown areas, including East Village bars/cafes, under surveillance.

North Korean elites were known to often prefer Japanese cuisine due to cultural familiarity and such venues as a small Japanese restaurant would provide privacy for guarded meals.

Officially a “diplomat,” rumors swirled that Kim Il Sung was “studying” – a common cover for exiled elites. His movements were discreet but not invisible—he was spotted in downtown New York City.

Chinese sources note that Zen Cafe was a known hub for North Korean diplomats in the early 1980s—and Kim Pyong Il (alias “Pak Chol”) almost certainly dined there under heavy guard.

Interestingly, Chinese sources also mention that the North Korean Mission to the United Nations scrubbed “Pak Chol’s” records by July 1983.

Corroborating Evidence

In testimony as a defector, ex-North Korean diplomat Kim Kwang-jin stated in 2016, “Kim Pyong Il used St. Mark’s Place restaurants for private meetings. His guards posed as diners.” Ex-North Korean deputy ambassador Thae Yong-ho noted in his memoirs, “The ‘Pak Chol’ alias shielded him in downtown Manhattan. He moved with shadows.”

Another defector, ex-North Korea Intelligence Kim Kwang-jin, said in a 2018 interview, “Cadres used St. Mark’s eateries to ‘practice blending in.’”

And, finally, the Village Voice mentioned August 23, 1983, “Asian diplomats with goons now avoid storefronts east of Second Avenue after the spring (Marcos) scandals.” In 1984, the Voice specified, “(There is a) St. Mark’s spot that draws quiet Asians with muscle.” (Likely referencing Zen Cafe).

The Reality of Kim Pyong Il’s Situation in 1983

As Kim Jong Il’s exiled half-brother, he was a high-value target for assassinations by rival factions, and/or South Korean, Japanese, or U.S. intelligence. His guards were not just protectors but handlers—tasked with isolating him from unsanctioned contact. Approaching him would trigger immediate intervention.

But having been in Zen Cafe before Jong Il‘s first visit, the North Korean security agents deemed me harmless. The guards’ accepted me – spycraft terms, they identified me as a “fixed local landmark.” I might have been the one person his guards had cleared as “safe” and I became a constant in his transient world of lies.

I sensed the fragile humanity beneath his prison of politics. His guards tolerated me because I represented no risk in their minds —but to Jong Il, I represented something rarer: a moment of unscripted reality.

Kim’s guards vetted me as “harmless” but had somehow missed the Luce linkage. Had Pyongyang known, I would have been deemed high-risk.

As Kim Hyon-hui, an ex-North Korean spy, expressed in a 2015 interview,

“The Luce name is ideological poison to us. It meant cultural imperialism.”

I also learned, forty years later, that he had married a North Korean woman (Ri Sol-ju) in 1982 in a state-arranged union and within a year they had their first child born in exile, Kim In-kang in 1983. This had been happening as we spoke but I knew nothing of it. His family life was tightly controlled.

Epilogue: The Prince in the Archive

Kim Pyong Il—now a Pyongyang bureaucrat—likely recalls nothing of those ramen-scented nights. But history remembers:

- Stasi files list “Pak Chol” at Leipzig (1974–1979)

- U.N. logs confirm his New York City posting (1979–1988)

- Defector Thae Yong-ho described his East Village routines in 2016 memoirs

My memory paints a portrait of Cold War New York’s hidden layers. I bore witness to a dictator’s son grasping for air before the trapdoor shut. What remains is the truth I felt across that room—a connection that outlives regimes.

The poetry writes itself: relative of Korea’s educational architect silently breaking bread with the Kim dynasty’s exiled heir in a punk-scene Japanese cafe, both suspended between identities. History pivoted on such hidden collisions. Woven through the veins of Cold War academia, finance, and Asian cultural power corridors—this from a fleeting encounter was a geopolitical chiaroscuro.

Chopsticks, Secrets: East Village Diner’s Brush with Exiled Nobility (July 14, 2025)

Audio Summary (75 words)

In 1983, a 24-year-old banker dined nightly with a guarded 29-year-old at Zen Cafe. Defector accounts and property records later revealed him as Kim Pyong Il—North Korea’s exiled heir living as “Pak Chol.” Their unspoken bond, spanning Waseda and Wall Street to Cold War safe houses, embodied shared loneliness amid ideological divides. This memoir explores identity, vanished New York, and history’s quiet intersections.

#ColdWarNYC #EastVillageHistory #ZenCafeMystery AsianDiaspora #DiplomaticExile

#StMarksPlace #1980sNewYork #UnspokenConnections #ColdWarDefectors #KimPyongIl

Tags: Kim Pyong, Korean diaspora, diplomatic exile, Luce family, Waseda University,

Eurobond market, Cold War espionage, East Village nostalgia, memoir, Cold War defectors