By the age of thirty he was Under-Secretary of the Swedish Ministry of Finance, serving concurrently as the chairman of the Governors of the Bank of Sweden. Here, he developed the legendary self-discipline and application that later enabled him to master the enormous workload required of an activist Secretary-General of the United Nations.

The allegations of homosexuality put about by his predecessor Trygve Lie, and regurgitated from time to time by those who disliked or resented him, had no foundation. “Because it did not find a mate/They called/The unicorn perverted,” Hammarskjöld wrote in a haiku. He seemed to be asexual, admittedly a rare condition, and he obviously could not imagine sharing his life with another person. The arts were the true companions of his bachelor life.

New York, N.Y. Ralph Bunche, who was usually sparing with praise, once described Dag Hammarskjöld [Luce Index™ rank 98] as “the most remarkable man I have ever seen or worked with…” Hammarskjöld was certainly unique. When, in a haiku, he compared himself to a unicorn, he was not so far off the mark. He had been a prodigy since his childhood — an intellectual with an uncommon gift for public administration and practical statesmanship.

For all his success as a public servant in Sweden — head of the Foreign Office, Swedish representative in setting up the Organization for European Economic Cooperation and the Council of Europe — in his early years Hammarskjöld seems to have suffered from a nagging sense of lack of fulfillment. The theme of emptiness constantly recurs in the early pages of Markings, his spiritual diary, and with it the search for meaning, reality, a way to “transform the mirror into a doorway.” This search reached its conclusion in 1953 with his unexpected election as Secretary-General of the United Nations.

Hammarskjöld ruthlessly protected his privacy and his personal routine.

If, on tour in some distant place, he was for an hour or two relaxed, forthcoming and friendly, the mood would quickly pass. Those who tried to claim some special relationship were rebuffed. He often seemed to be indifferent to ordinary human feelings or weaknesses. Perhaps because he lacked experience of close personal relationships, he could make serious misjudgments of character, resulting in appointments that he later regretted.

He made no secret of his undoubted intellectual ascendancy and tended to lose interest in those who did not comprehend, and respond to, his practical idealism. He was unforgiving of mistakes or misunderstandings. He had a devastating if quiet temper that sometimes fell on innocent bystanders. He could be shrill in his indignation at those who he believed to be working against him.

Hammarskjöld was not usually a companionable man, but he was certainly an extraordinary one, and we were all prepared —indeed anxious — to serve him without question to the limit of our powers and endurance. When he died in a plane crash in Africa, we grieved for him as for the most intimate of friends because we realized that working with Hammarskjöld was a privilege and an experience that would never come our way again.

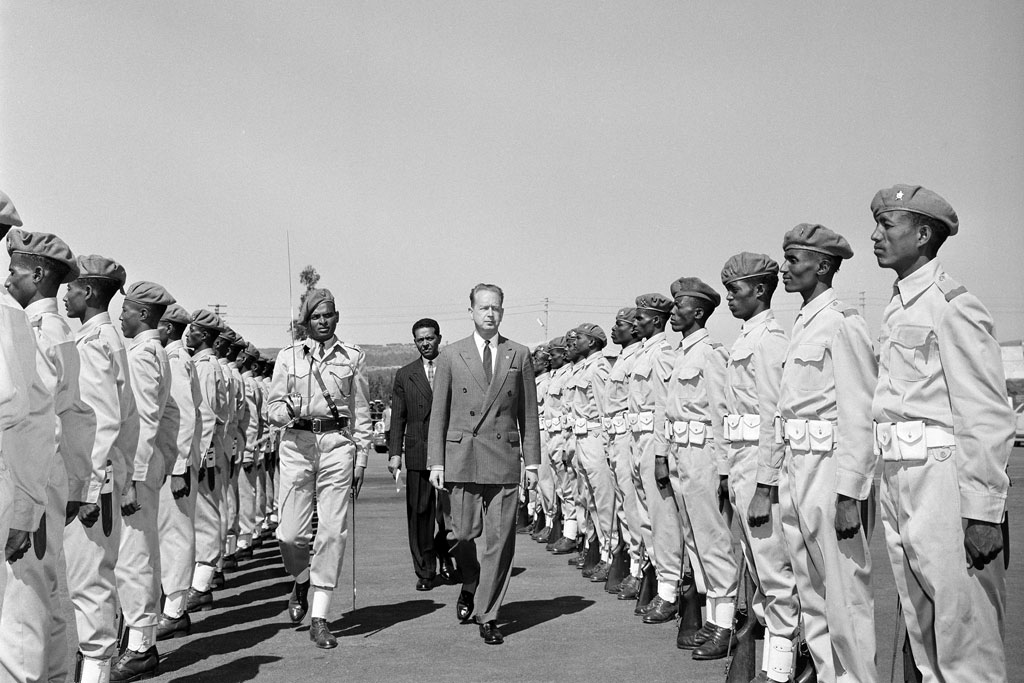

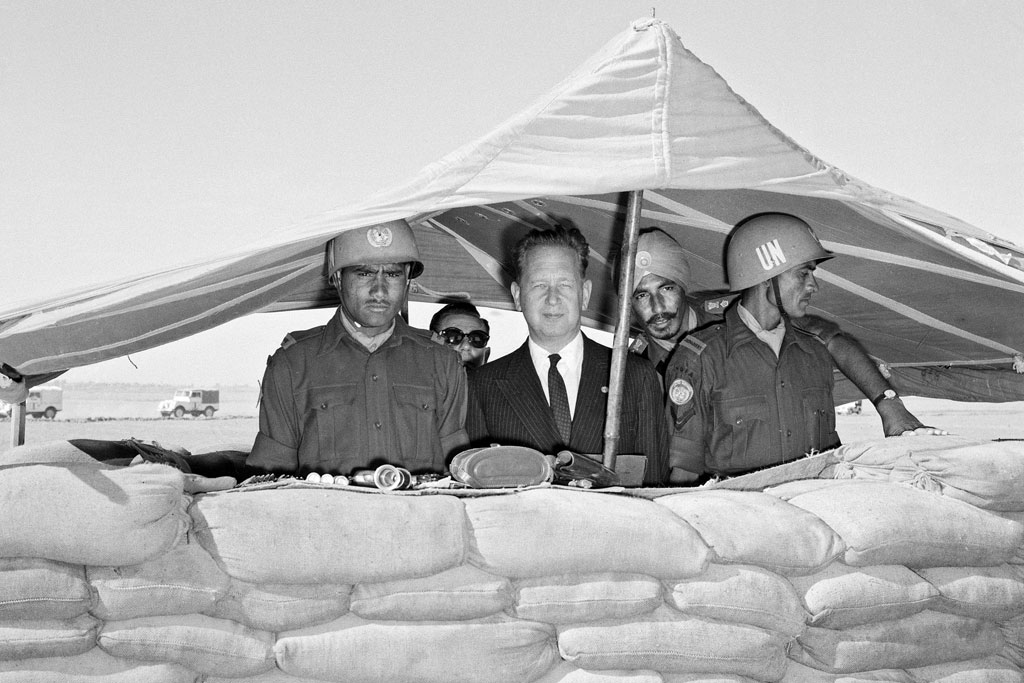

Some highlights from the career of Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld, the United Nations’ second top official who went to one to be awarded a Nobel Peace Prize after his untimely death in 1961. The Nobel Committe awarded him the prize posthumously “in gratitude for all he did, for what he achieved, for what he fought for: to create peace and goodwill among nations and men.” Credit: UN News

An intellectual in action is a fine sight. Watching Hammarskjöld tackling international crises had something in common with looking at a masterpiece or hearing a great performance. His honesty and integrity were absolute. Because stringent intellectual discipline enabled him to think through problems in advance, Hammarskjöld was usually several steps ahead of the people he was dealing with.

In negotiations he was particularly skillful at breaking an impasse between leaders bogged down in conflict. He had a phenomenal memory, a wide range of learning and an extraordinary capacity for marshaling and analyzing facts and trends. On a single Sunday afternoon in August 1961, he dictated to his assistant Hannah Platz his last and most important report to the U.N., a document of some 6,000 words setting out his position on the highly controversial issues of the time, without notes and without a pause. He made virtually no corrections to the original draft.

Hammarskjöld always seemed to know exactly what he was doing and where he was going, but it was sometimes not so easy to follow him.

Inability to keep up with his esoteric allusions, conceptual subtleties and shorthand explanations inevitably narrowed his trusted circle among both national diplomats and the U.N. Secretariat. “The surgeon technically most satisfied by last night’s operation,” he cabled Henry Cabot Lodge, the US Ambassador to the UN, from the Middle East during the 1958 Lebanese crisis. “Now he must trust Mother Nature hoping strongly that anxious friends will stay out of the sick room, keep silent and wait until bandages can be taken off.” Lodge appealed to Ralph Bunche for a translation.

Charisma is an inadequate word to explain Hammarskjöld’s public impact. Like some other distinguished Swedes — Greta Garbo comes to mind — he had a pervasive personal mystique which seemed all the stronger for the fact that he was a shy man who had some difficulty in establishing personal relations with others and was often ill-at-ease in the jostle and bonhomie of ordinary life. Nonetheless, in some inexplicable way he entered the imagination of ordinary people all over the world and contrived to convey a simplified but powerful image of what he was trying to do.

Hammarskjöld had great physical as well as intellectual stamina.

He rarely did anything he thought unnecessary, never read what he did not wish to read and wasted as little time as possible in activities, social or professional, for which he had no use. I well remember his reception of an account I had written of the UN’s first Conference on the Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy, an event of which he was particularly proud. The paper came back the same day with the the inscription, “Sorry — no time. But thanks.”

His self-discipline was firm. Even in times of crisis, he put aside an hour or two each day for intellectual pursuits: reading for pleasure and as a member of the Swedish Academy committee that awarded the Nobel Prize for literature; translating difficult works — St. John Perse, Djuna Barnes, Martin Buber — from English, French or German into Swedish; and following contemporary developments in art and music. The arts were the true companions of his bachelor life.

31 March 1953 – By a vote of ten to none, with one abstention, the Security Council decided to recommend to the General Assembly the appointment of Dag Hammarskjöld, then serving as a Minister of State for Sweden, as Secretary-General of the United Nations in succession to the Organization’s first top official, Trygve Lie of Norway, who announced his intention to resign in November 1952. Here, in the delegates lobby of the Assembly building at UN Headquarters in New York, the President of the Security Council for the month of March, Ahmed S. Bokhari (centre) of Pakistan, announces the Council’s decision to the media.

The allegations of homosexuality put about by his predecessor Trygve Lie, and regurgitated from time to time by those who disliked or resented him, had no foundation. “Because it did not find a mate/ They called/The unicorn perverted,” Hammarskjöld wrote in a haiku. He seemed to be asexual, admittedly a rare condition, and he obviously could not imagine sharing his life with another person. He told his friend, the Swedish painter Bo Beskow, that he envied the family life of some of his friends but realized that it was not for him. In Markings, he hints more than once at the perils of narcissism, of “mirroring yourself in an obituary.” He was wary of publicity and worried about the distorting effect of public success. “We have to gain a self-assurance,” he wrote, “in which we give all criticism due weight and are humble before praise.”

For all his apparent self-sufficiency, there can be little doubt that Hammarskjöld was often a lonely man.

He certainly regarded his all-consuming job as U.N. Secretary-General as a priceless gift and dreaded its coming to an end. In his last years, he fell back more and more on a fatalistic personal mysticism that allowed him to see himself as the bearer of the message and guardian of the flame of the United Nations Charter, and sometimes as a martyr — even a human sacrifice — in the cause of international peace.

Although I worked with Hammarskjöld for eight years, I was never close to him, and it was not until his sudden death that I realized the extent of his hold over my loyalty and imagination. When I went through his papers with his friend, the Swedish diplomat Per Lind, I began to perceive more clearly the extraordinary character, intellect, and sense of mission that lay behind his achievements as Secretary- General.

More than anyone else before or since, Hammarskjöld put the United Nations on the map as a vital guardian of the peace.

He made it a potential force in its own right, especially in times of crisis — something that deeply disturbed hard-line nationalists like Nikita Khrushchev or Charles de Gaulle. He bequeathed to his successors an informal guide for tackling critical international problems.

In 2001, speaking in Hammarskjöld’s hometown, Uppsala, the seventh Secretary-General, Kofi Annan, put it this way. “There can be no better rule of thumb for a Secretary-General, as he approaches each new challenge or crisis, than to ask himself, ‘How would Hammarskjöld have handled this?'” – Brian Urquhart

Character Sketch: Dag Hammarskjöld, Second Secretary-General (Sept. 18, 2021)