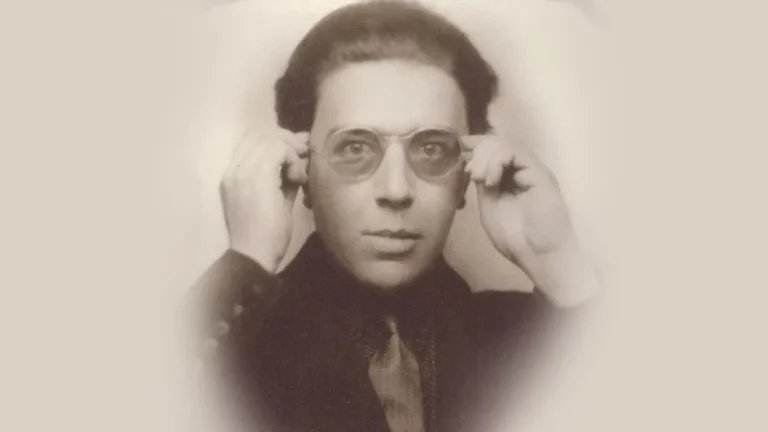

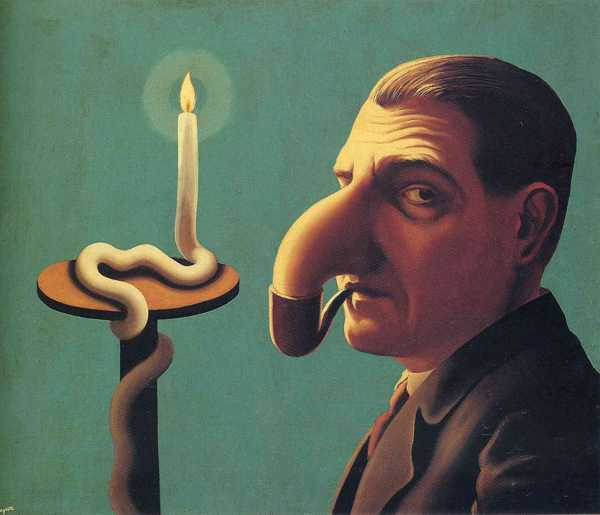

Paris –– André Breton (1896–1966) stands as one of the most influential figures in 20th-century art and literature, a poet and theorist whose radical ideas birthed the surrealist movement. Known as the co-founder, leader, and principal theorist of Surrealism, Breton’s legacy is etched in his groundbreaking writings, including the Surrealist Manifesto of 1924, where he famously defined surrealism as “pure psychic automatism.” This concept—unleashing the unconscious mind to create art free from rational constraints—revolutionized creative expression and cemented Breton’s status as a titan of modernist thought.

Born in Normandy, France, to a modest family, Breton’s early life foreshadowed his unconventional path. His father, a policeman and staunch atheist, and his mother, a former seamstress, provided a grounded upbringing. Yet Breton’s intellectual curiosity led him to medical school, where he developed a fascination with mental illness—an interest that would later inform his surrealist explorations. World War I interrupted his studies, thrusting him into a neurological ward in Nantes. There, he encountered Jacques Vaché, a provocative figure whose disdain for artistic norms and tragic suicide at 23 left a lasting imprint on Breton’s worldview.

Breton’s journey into the avant-garde began in earnest with the Dada movement. In 1919, alongside Louis Aragon and Philippe Soupault, he launched the review Littérature, collaborating with Dadaist Tristan Tzara. However, Breton soon transcended Dada’s nihilism, seeking a more constructive vision. In 1924, he published the Surrealist Manifesto, founding La Révolution surréaliste magazine and the Bureau of Surrealist Research. A constellation of writers—Paul Éluard, Antonin Artaud, Robert Desnos, and others—rallied around him, forming the nucleus of the surrealist movement.

Breton’s ambition extended beyond art; he sought to fuse personal transformation, inspired by Arthur Rimbaud, with Marxist politics. Joining the French Communist Party in 1927, he aimed to align surrealism with revolutionary ideals. Yet his fiercely independent spirit clashed with party dogma, leading to his expulsion in 1933. This tension surfaced again in 1935, when Soviet writer Ilya Ehrenburg’s scathing critique of surrealists as parasitic deviants prompted Breton to slap him publicly—an act that saw surrealists barred from a writers’ congress.

Breton’s literary output was as provocative as his politics.

His 1928 novel Nadja, a dreamy recounting of an encounter with a woman descending into mental illness, showcased his mastery of surrealist narrative. Yet controversy shadowed his career. The 1929 Second Surrealist Manifesto included a notorious line—“The simplest surrealist act consists… of descending into the street and shooting at random… into the crowd”—drawing ire from peers like Albert Camus and sparking a 1930 pamphlet, Un Cadavre, denouncing his leadership. Breton later clarified this as a rhetorical flourish, not a literal call to violence, but the rift among surrealists deepened.

The 1930s brought personal and global upheaval.

Economic depression forced Breton to sell his vast art collection—over 5,300 items amassed in his Paris apartment on rue Fontaine—though he later rebuilt it. In 1938, a French government commission took him to Mexico, which he declared “the most surrealist country in the world.” There, he met Leon Trotsky, co-authoring the Manifesto for an Independent Revolutionary Art with Diego Rivera, advocating for art’s liberation amid rising totalitarianism.

World War II forced Breton into exile.

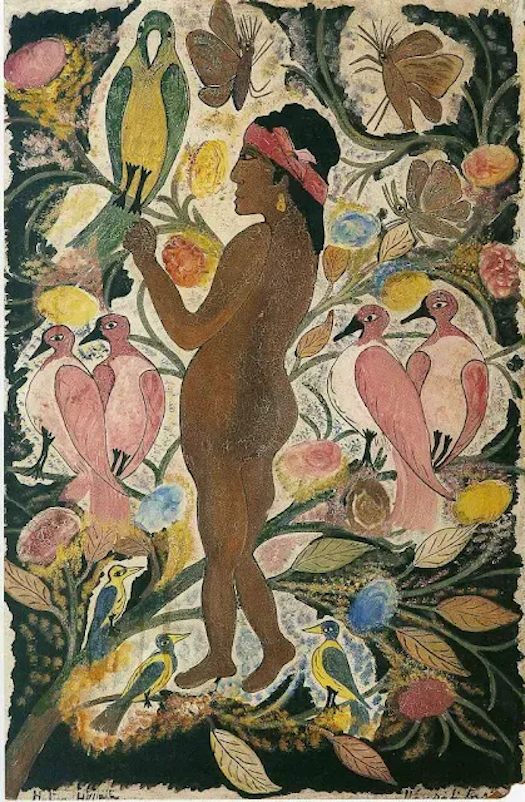

Escaping Vichy France’s ban on his “subversive” writings, he fled to the United States in 1941 with aid from Americans Varian Fry and Hiram Bingham IV. In New York, he organized a landmark surrealist exhibition at Yale in 1942 and collaborated with artists like Wifredo Lam. His encounter with Martinican writers Aimé and Suzanne Césaire enriched his work, as did his 1945–46 visit to Haiti. Martinican literature is primarily written in French or Creole and draws upon influences from African, French and Indigenous traditions, as well as from various other cultures represented in Martinique.

In Haiti, Breton connected surrealism to Vodou and the Haitian Revolution, championing painter Hector Hyppolite’s vivid depictions of lwa deities. His lectures inadvertently fueled a student uprising that toppled President Élie Lescot, though Breton downplayed his role, crediting the Haitian people’s pent-up frustration.

Returning to Paris in 1946, Breton opposed French colonialism—signing the Manifesto of the 121 against the Algerian War—and nurtured a second wave of surrealists through exhibitions and the review La Brèche (1961–65). A lifelong atheist like his father, he supported the Anarchist Federation, rejecting authoritarianism in all forms. Breton died in 1966 at 70, leaving an indelible mark on art, literature, and revolutionary thought.

Breton’s life was a tapestry of contradictions: a medical student turned poet, a communist expelled for nonconformity, a leader both revered and reviled. His surrealism—wild, dreamlike, and defiant—challenged the status quo, inviting creators to plumb the depths of the unconscious. From Nadja to his Mexican epiphanies, from Parisian studios to Haitian streets, André Breton remains a towering figure whose vision continues to inspire.

#AndreBreton, #Surrealism, #SurrealistManifesto, #FrenchLiterature, #20thCenturyArt, #AvantGarde, #Nadja, #ArtRevolution, #ParisArt, #TrotskyMexico

André Breton: Rebel Poet Who Dreamed Surrealism into Existence (Feb. 21, 2025)