Venturing into a perilous and unknown sea, New England whalers from the Luce family and others found immense fortune, fierce storms, and a hostile shore in 1840s Korea.

New York, N.Y. — From the bustling docks of New Bedford, Massachusetts, they set sail, their holds filled with empty barrels and their minds with dreams of fortune. They were bound for the far side of the world, a place so remote it existed only as a blank space on their charts: the East Sea of Korea.

The mid-1840s witnessed a quiet invasion of the East Sea’s peaceful isolation. Large, three-masted vessels, their sails patched and their decks stained with soot and oil, began to appear off the Korean coast. They flew the red, white, and blue flag of the United States, and they were crewed by a motley collection of men from New England, the Azores, Cape Verde, and beyond.

Their mission was singular: to hunt the great whales that

swam in the cold, deep waters between Korea and Japan.

Driven by the insatiable demand for whale oil to light the lamps and lubricate the machines of the Industrial Revolution, these American whalers, many hailing from the Luce family of Martha’s Vineyard, embarked on a chapter of maritime history defined by both staggering profit and profound peril.

The Allure of a Virgin Whaling Ground

By 1843, the U.S. whaling fleet was a global industrial powerhouse, with nearly 643 ships turning the ports of New England into boomtowns. New Bedford, Massachusetts, was the undisputed capital, its fortunes literally built on blubber. As established whaling grounds in the Atlantic and Pacific became increasingly depleted, ship owners and captains were forced to look for new, unexploited territories. Whispers and logbook entries began to speak of a new El Dorado for whalers: the East Sea.

The Korea Strait became the gateway to this promised land. Ships would sail past the volcanic cliffs of Japan and through the narrow passage, emerging into a sea one captain described as teeming with whales “so numerous that we had no occasion to chase them with our ship: We had nothing to do but to lower our boats, harpoon them and bring them alongside for stripping.”

This account, from Captain John H. Peck of the Milton, painted a picture of almost effortless harvest. For captains and ship owners, this meant a quick fill of the holds and a rapid return to port with a valuable cargo of whale oil and baleen, the bone-like substance used for corsets and buggy whips. The potential for immense wealth was a siren call that the industry could not resist.

A Floating Factory of Filth and Deprivation

The romantic image of the whaler, however, was a stark contrast to the grim reality of life aboard ship. These vessels were not sleek clipper ships but slow, sturdy floating factories. The processing of a whale was a brutal, round-the-clock operation that transformed the ship into a reeking slaughterhouse. The deck became a slick, dangerous surface of grease and blood, while the try-works—the brick furnaces used to render blubber into oil—belched thick, acrid smoke and coated everything in a layer of greasy soot.

According to Professor Curtis Martin, an expert on maritime history, the crew’s quarters were “literally a rat’s nest.” The stench from the deck permeated everything below. Fresh water was a precious commodity, strictly rationed for drinking, not washing. Sailors’ memoirs describe hanging their tin cups and plates near their bunks after a meal, only to find them cleaned by cockroaches by morning.

Vermin were a constant plague; rats, lice, and bedbugs were ubiquitous companions for the crew, who slept in cramped, damp forecastles. The food, typically hardtack and salted meat, was often barely edible, and morale was intrinsically tied to the quality of the occasional fresh meal.

The Perils of a Hostile and Unforgiving Coast

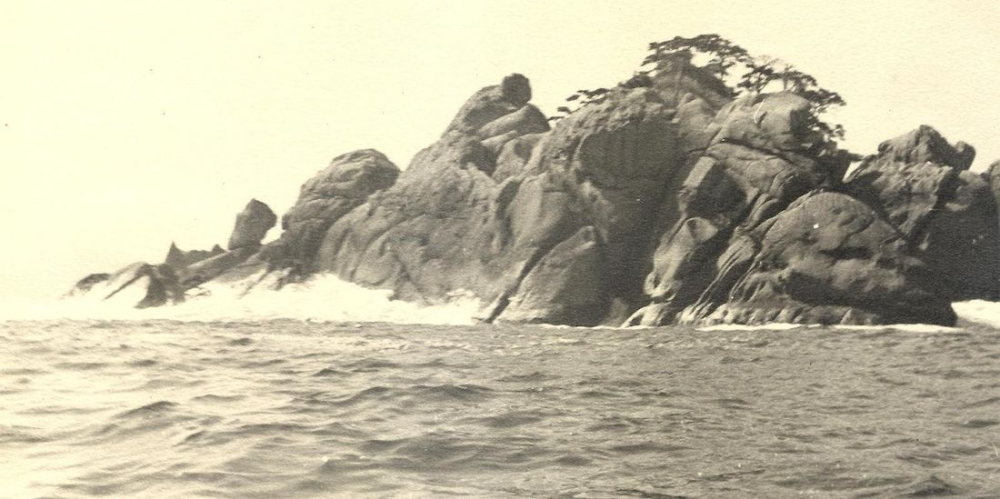

The dangers of whaling were monumental even under ideal conditions. A thrashing whale could easily smash a whaleboat to splinters, drowning or maiming the crew. But for those in the East Sea, the environment itself was a primary antagonist. The weather was notoriously unpredictable, with sudden, violent storms that could push a ship onto a lee shore. Navigation was fraught with hazard; Korean charts were nonexistent in the West, and the rocky, uncharted coastline was a ship-killer.

Furthermore, Korea in the 1840’s was the “Hermit Kingdom,” a nation fiercely resistant to foreign contact. The Joseon Dynasty enforced a policy of isolation, and any foreign sailors who shipwrecked or came ashore were often imprisoned, or worse. This made resupply or seeking aid an immense risk.

While a New Bedford newspaper might recommend Hong Kong for its efficient British police and abundant supplies of “beef, pigs, yams [and] sweet potatoes,” it was a journey of weeks away. For a ship damaged in a storm or running low on provisions, the welcoming port was a distant dream, and the nearby Korean coast was a deadly threat.

Mutiny, Desertion, and the Human Toll

The combination of harsh conditions, constant danger, and the psychological strain of a multi-year voyage often proved too much for the crews. These were not always seasoned mariners; many were young, inexperienced men lured by the promise of a share of the profits, only to find themselves trapped in a floating hell. Some had joined to escape past misdeeds or social stigma, and they chafed under the rigid, often draconian discipline of the ship’s officers.

The threat of brutal punishment could not always quell discontent. Demoralized crews were prone to desertion if an opportunity presented itself in a remote port, and mutiny was a constant, lurking fear for every captain. A failed voyage could leave a sailor not only penniless but in debt to the ship’s owners, forcing him to sign on for another grueling expedition simply to break even.

The human cost of this industry was etched into the faces of the men and recorded in the logs of ships that never returned to their home port, lost to the sea, the whale, or the unforgiving coast of a hidden kingdom.

The era of the American whaler in the East Sea was brief but intense. By the late 1850s, the opening of Japanese ports like Hakodate in Hokkaido provided safer havens, and the gradual depletion of the whale populations pushed the fleet elsewhere. The discovery of petroleum in Pennsylvania in 1859 spelled the beginning of the end for the industry.

Yet, for a few short years, the rugged coast of Korea formed the backdrop for an extraordinary tale of adventure, where New England mariners, including the intrepid Luce family, ventured into the unknown, seeking fortune and finding instead a legacy of peril on the deep, blue waves of the East Sea.

Summary

In the 1840s, American whaling ships from New England, including captains from the Luce family, breached the isolation of Korea’s East Sea. They discovered incredibly rich whaling grounds, but faced immense perils: violent storms, an uncharted and hostile coast, and brutal living conditions aboard their ships. This is the story of their brief, profitable, and dangerous adventure in the waters of the Hermit Kingdom.

#AmericanWhalers #HermitKingdom #WhalingHistory #NewBedford #EastSea

#MaritimeHistory #LuceFamily #19thCentury #Korea #AdventureHistory

TAGS: American whaling, Joseon Dynasty, Hermit Kingdom, New Bedford, 19th century Korea,

Martha’s Vineyard, Luce family, East Sea, maritime adventure, whale oil, ship life, mutiny, desertion

Facebook: In the 1840s, Yankee whalers from the Luce family and others sailed into the uncharted waters of Korea’s East Sea. They found a whale hunter’s paradise—and a perfect storm of danger. Discover the true story of fortune, filth, and fear on the high seas in our latest deep-dive feature. #MaritimeHistory #AmericanWhalers #Korea

Instagram: Fortune & peril in the Hermit Kingdom’s sea. 🐋 In the 1840s, American whalers from New England braved uncharted waters, hostile shores, and brutal conditions to hunt in Korea’s East Sea. Link in bio to read the full story of adventure on the edge of the map. #WhalingHistory #AmericanWhalers #EastSea #MaritimeAdventure #History

LinkedIn: The 1840s American whaling venture into Korea’s East Sea presents a fascinating case study in high-risk, high-reward exploration. Our new feature examines the logistics, leadership, and immense challenges faced by these maritime entrepreneurs, including captains from the Luce family, as they operated in a completely unknown and hostile environment. #MaritimeHistory #Leadership #Exploration #BusinessHistory

X/Twitter: Yankee whalers in the Hermit Kingdom: a story of immense profit and profound peril. How New Englanders like the Luce family hunted whales in Korea’s East Sea in the 1840s, facing storms, mutiny, and a hostile shore. #WhalingHistory #AmericanHistory #Korea

BlueSky: The East Sea, 1845. American whaling ships, their decks slick with blood and oil, hunt in waters off a hostile Korea. A new feature tells this gritty tale of the Luce family and other mariners seeking fortune at the world’s edge. #Maritime #History #Whaling