Reflecting on a Complex Legacy of Faith, Power, and Controversy from a Former Critic’s Perspective

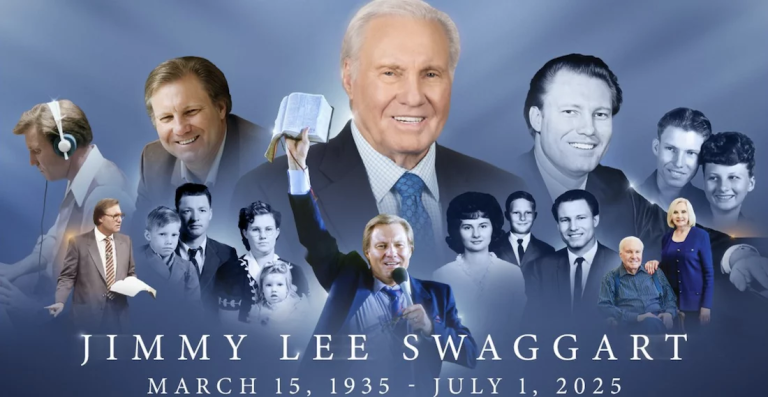

New York, N.Y. – As the news of Jimmy Swaggart‘s passing on July 1, 2025, at the age of 90 reverberates through religious and media circles, I find myself compelled to reflect on a figure who once commanded an empire of faith but whose story became synonymous with hubris and human frailty.

As the founder of Fundamentalists Anonymous in the 1980s, I stood in opposition to the televangelist juggernaut that Swaggart epitomized, testifying before Congress about the financial and emotional exploitation woven into such ministries.

His death, following a heart attack that led to intensive care, marks the end of an era defined by soaring sermons, multimillion-dollar revenues, and shattering scandals. From my vantage point as a former Wall Street banker turned activist, Swaggart‘s life offers a cautionary tale about the perils of unchecked authority in religion.

Born on March 15, 1935, in Ferriday, Louisiana, Jimmy Lee Swaggart grew up in a Pentecostal household that nurtured his early talents in music and preaching. Cousins to rock ‘n’ roll legends Jerry Lee Lewis and Mickey Gilley, Swaggart chose the path of evangelism over secular stardom, honing his skills in small churches across the South.

By the 1950s, he had released gospel albums and begun broadcasting on radio, laying the groundwork for what would become one of the most influential ministries in U.S. history. His fiery style, blending emotional appeals with condemnations of sin, resonated with audiences seeking spiritual certainty in turbulent times.

The Ascent to Televangelist Stardom

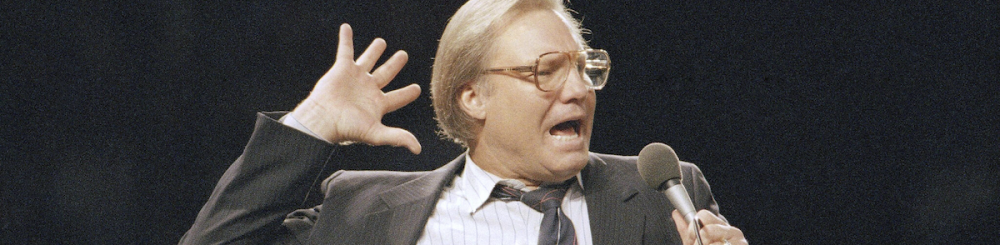

Swaggart‘s rise accelerated in the 1970s with the advent of television. Launching “The Jimmy Swaggart Telecast” in 1971, he expanded his reach exponentially. By the mid-1980s, his program aired on over 200 stations, reaching an estimated two million viewers weekly in the U.S. alone, with global broadcasts extending to more than 100 countries.

Financially, the ministry was a powerhouse: in 1985, it generated approximately US$140 million (equivalent to about US$400 million in today’s dollars, adjusted for inflation) annually through donations, book sales, and merchandise.

This revenue funded expansive operations, including Jimmy Swaggart Bible College (later renamed World Evangelism Bible College) in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, which spanned 257 acres (104 ha) and educated thousands of aspiring ministers.

What set Swaggart apart was his unyielding Pentecostal fervor. He preached against rock music, calling it “the new pornography,” and lambasted fellow evangelists for moral lapses. Ironically, this self-appointed guardian of purity would later face accusations of hypocrisy.

His sermons, often delivered with tears and dramatic gestures, emphasized personal salvation and the dangers of worldly temptations.

Supporters saw him as a prophet; critics, including myself, viewed his empire as a sophisticated fundraising machine that preyed on vulnerable believers.

During my time leading Fundamentalists Anonymous, we received countless calls from individuals who had donated their life savings to such ministries, only to feel spiritually bankrupt afterward.

Swaggart‘s influence extended beyond the pulpit. He authored numerous books, including “To Cross a River” (1977), an autobiography detailing his humble beginnings, and produced music that sold millions of copies.

His ministry’s headquarters in Baton Rouge became a sprawling complex, complete with a 7,000-seat Family Worship Center.

At its peak, the organization employed hundreds and boasted assets valued in the hundreds of millions. Yet, beneath the gloss lay systemic issues: allegations of financial opacity and emotional manipulation that echoed the concerns I raised in my congressional testimony.

Scandals That Shook the Foundations

The cracks in Swaggart‘s facade began to show in the late 1980s, a period rife with televangelist controversies. In 1986, he played a role in exposing rival Jim Bakker’s financial and sexual improprieties at the PTL Club, positioning himself as a moral arbiter. However, this victory was short-lived.

On February 21, 1988, Swaggart delivered his infamous tearful confession on live television: “I have sinned against you, my Lord, and I would ask that your precious blood would wash and cleanse every stain until it is in the seas of God’s forgiveness.”

This admission followed revelations that he had been photographed entering a motel with sex worker Debra Murphree in Metairie, Louisiana.

The scandal, orchestrated in part by fellow minister Marvin Gorman seeking revenge for Swaggart‘s earlier accusations against him, led to Swaggart‘s defrocking by the Assemblies of God.

The fallout was swift and severe. Viewership plummeted by 85%, and revenues dropped dramatically, forcing layoffs and asset sales.

In 1991, another scandal emerged when Swaggart was stopped by police in Indio, California, with prostitute Rosemary Garcia in his car. Though no charges were filed, the incident further eroded his credibility.

These events validated the warnings Fundamentalists Anonymous had issued about the “religious addiction” fostered by authoritarian figures— a concept I introduced on the Phil Donahue Show in 1985, prompting 17,000 calls for help and leading me to abandon my banking career at Daiwa Bank.

From my perspective, these scandals were not mere personal failings but symptomatic of a broader system.

Televangelists like Swaggart amassed fortunes—his ministry once reported US$150 million (approximately €140 million at the time) in annual income—while urging followers to give sacrificially.

We documented cases where donors faced financial ruin, mirroring the exploitation we testified about in Congress. Swaggart‘s refusal to fully submit to denominational discipline, opting instead to continue independently, underscored his defiance.

Personal Encounters and Congressional Testimony

My direct involvement with Swaggart began in the heat of our crusade against televangelism’s excesses. On August 29, 1987, during a revival crusade on Long Island, my co-founder Richard Yao and I attended to observe and distribute literature.

As Swaggart exited the stadium, surrounded by security, he spotted us and, in a

bizarre twist, invited us to his hotel room to “party” before climbing into his limousine.

This encounter, laden with irony given his public persona, fueled our resolve.

In 1988, Richard and I testified before the U.S. House Ways and Means Subcommittee on Oversight, decrying the lack of accountability in religious nonprofits. We highlighted Swaggart alongside Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson, arguing that their empires exploited tax-exempt status to build personal wealth.

Our organization, by then boasting 30,000 members across 41 chapters with a US$300,000 budget, provided support groups for those recovering from fundamentalist indoctrination. We even coordinated the first panel on religious addiction at the American Psychological Association’s convention in 1987, with findings published in the Journal of Religion and Health.

These efforts contributed to greater scrutiny: Congress considered reforms, though few materialized. Swaggart‘s scandals amplified our message, as his tearful apology became a cultural touchstone, parodied on shows like Saturday Night Live. Yet, for the victims—those who felt betrayed by the very figures promising salvation— the damage was profound.

A Complicated Legacy in Retrospect

In his later years, Swaggart rebuilt a scaled-down ministry, focusing on SonLife Broadcasting Network, which reached audiences via cable and online platforms. He continued preaching until health issues sidelined him, with his son Donnie assuming greater roles.

By 2025, the ministry’s influence had waned, but its endurance spoke to Swaggart‘s resilience. He leaves behind a family, including wife Frances, son Donnie, and grandchildren active in the church.

Reflecting as someone who once challenged him head-on, I see Swaggart‘s life as a mosaic of genuine faith marred by ambition. His contributions to gospel music and global evangelism are undeniable, having inspired millions.

Yet, the scandals exposed the vulnerabilities in charismatic leadership, reinforcing the need for transparency in religious institutions. Through Fundamentalists Anonymous, we helped countless individuals reclaim their autonomy, a mission that outlasted the headlines.

Swaggart‘s death closes a chapter, but the questions he raised about faith, power, and accountability endure. In an era of digital ministries and megachurches, his story reminds us that true spirituality thrives not in empires, but in humility and ethical stewardship.

Death | Rise and Scandalous Fall of Televangelist Jimmy Swaggart (Aug. 24, 2025)

Summary

In this personal obituary, Jim Luce, founder of Fundamentalists Anonymous, recounts Jimmy Swaggart’s rise from Louisiana preacher to global televangelist, his multimillion-dollar empire, and the 1988 prostitution scandals that led to his downfall. Luce shares his congressional testimony against Swaggart and a peculiar 1987 encounter, reflecting on a legacy of faith tainted by hypocrisy and exploitation.

#JimmySwaggart #ReligiousScandal #Fundamentalism #FaithAndPower

#EvangelismLegacy #CongressionalTestimony #ReligiousAddiction #Televangelist

Tags: Jimmy Swaggart, obituary, Jim Luce, Fundamentalists Anonymous, televangelist scandal,

Pentecostalism, religious exploitation, 1980s activism, congressional hearing, Baton Rouge ministry