Honoring America’s Farmworkers, Their Resilience, and the Essential Labor That Sustains U.S. Tables

New York, N.Y. — Every August 6th, communities nationwide pause to mark Farmworker Appreciation Day—a moment set aside to recognize those who commit their lives to the labor-intensive work that keeps families nourished across the United States.

But the origins of this day are not simple, nor are the roads its honorees have walked. Stretching back to the earliest colonial years, the story of farm labor is one forged through hardship, resilience, and relentless advocacy. Today’s appreciation forms the latest chapter in a narrative shaped by struggle, diversity, and hope.

From Indentured Servitude to Enslavement

Farm labor in the territories that would become the United States began in earnest during the 1600s. Facing daunting tracks of land and a scarcity of workers, colonial landowners first turned to indentured servants—mostly white men, women, and children from Britain or Germany.

These individuals signed contracts, binding themselves to four to seven years of grueling work in exchange for passage to the colonies, food, and sometimes, a modest sum or plot of land upon release. However, lives under indenture were beset with exploitation, miserable living conditions, and abuses of power; forceful recruitment and even the separation of families were not uncommon.

By the late 17th century, as the demand for labor outpaced what indentured servitude could supply, plantation owners looked elsewhere. With the expansion of colonial agricultural output, African slavery became the preferred mechanism of labor acquisition.

Enslaved Africans, wrenched from their homelands, became the backbone of the colonial agricultural economy, especially across Southern plantations. Unlike their white or free Black predecessors under indenture, enslaved Africans labored without the hope of release or recompense.

By the end of the American Revolution, people of African descent accounted

for roughly 20% of the colonial population, most of whom remained

enslaved well after Congress banned the international slave trade in 1808.

New Faces in the Fields: Asian and Mexican Labor

The abolition of slavery after the Civil War did not eliminate the need for agricultural workers.

Instead, the focus turned westward, particularly to California, which would become the nation’s leading agricultural state.

Chinese and Japanese immigrants, followed by Filipino laborers, found themselves at the mercy of brutal work, low pay, and racially motivated exclusion.

As a result of changing immigration laws and the increasing demand for cheap, pliable labor, the recruitment of workers from Mexico steadily rose in the early twentieth century.

With the onset of World War II, U.S. crops and industries suffered severe labor shortages. In response, the United States and Mexico launched the Bracero Program in 1942.

Through this initiative, more than four million Mexican men, called “braceros,” were contracted to work in American fields and railroads.

Though the program promised fair treatment and wages, reality often fell short. Braceros faced discrimination, poor living conditions, wage theft, and little recourse to challenge abuses.

Nonetheless, the Bracero era from 1942 to 1964 marked a profound demographic shift in the U.S. farm labor force, cementing the presence of Latin American workers who, to this day, make up the majority of the country’s agricultural workforce.

A Movement Grows:

Unions and Strikes Spur Recognition

The 1960s proved a turning point. In California and beyond, Filipino and Mexican farm laborers—exploited, underpaid, and denied basic protections—stood up for their rights.

Their actions, beginning with a grape strike led by Filipino workers in Delano, California, spurred the formation of the United Farm Workers (UFW) union, led by a multiracial coalition of advocates.

The UFW and its leaders, such as Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta, and Larry Itliong, championed nonviolent protests, hunger strikes, and boycotts in pursuit of fair wages, decent housing, and dignity on the job.

Their victories reverberated far beyond the fields, pushing farmworker issues into the national spotlight and improving the lives of countless agricultural workers.

Official Recognition and Ongoing Advocacy

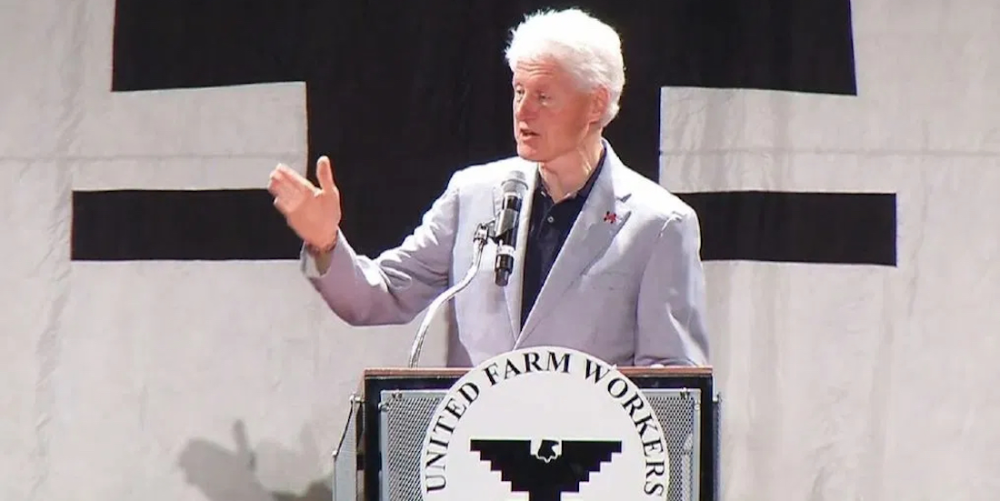

The first formal observance of Farmworker Appreciation Day arose from these mobilizations. Initially celebrated in September to align with a traditional harvest feast day, the occasion became nationally recognized in August when, in 1994, President Bill Clinton officially proclaimed August 6th as Farmworker Appreciation Day.

Each year since, advocates, unions, and communities have used the day to draw attention not only to the contributions of farmworkers—who continue to face hazardous conditions, wage theft, and vulnerability as immigrants—but also to the necessity of policy and cultural change to support their well-being.

Living Legacies: Why We Celebrate

Farmworker Appreciation Day serves as an urgent reminder of the hands that feed the nation—of the sacrifices made under colonial servitude, the inhumanity of slavery, the endurance of immigrants, and the courage of those who organized for justice. In honoring farmworkers today, we honor a lineage of resilience and a future where every worker is valued.

Summary

Farmworker Appreciation Day, observed August 6th, honors the contributions of U.S. agricultural workers—a tradition rooted in centuries of struggle. The story begins with indentured servitude and slavery during colonial times, shifts through immigrant labor, and finds hope in the farmworker movements of the 1960s. Today, the day offers not only gratitude for those who feed the nation but also a call to recognize their labor, rights, and ongoing resilience.

#FarmworkerAppreciationDay #FarmworkerHistory #USLaborMovement #HonorFarmworkers

#UnitedFarmWorkers #AgriculturalJustice #August6 #LaborRights #FoodJustice #ImmigrantLabor

TAGS: U.S. agriculture, Farmworker Appreciation Day, indentured servitude, American history,

labor rights, African slavery, Bracero Program, United Farm Workers, immigrant labor, farm labor