How U.S. Cold War Politics Fueled Central America’s Bloodiest Modern Conflict

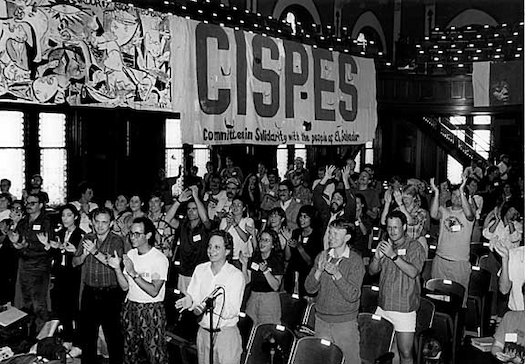

New York, N.Y. — Living in New York City in 1983, I had several friends who were sympathetic to the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN). They belonged to CISPES. Back then, the subway had tokens — and FMLN supporters in New York sold fake tokens at half price to raise funds for the struggle.

Those counterfeit subway tokens, stamped with “Good for One Fare” and sold in Washington Square Park for fifty cents instead of a dollar, represented something larger than transit fraud. They symbolized how El Salvador’s brutal civil war had reached into the daily lives of Americans, even those thousands of miles from the battlefields of Central America.

The Roots of Revolutionary War

The Salvadoran Civil War that raged from 1979 to 1992 didn’t emerge from a vacuum.

For decades, El Salvador’s oligarchy — known as “the fourteen families” including the Dueñas family — controlled vast coffee plantations while the majority of the population lived in crushing poverty.

By 1979, two percent of the population owned sixty percent of the land, while 300,000 families were landless.

The Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front, or FMLN, formed in 1980 when five leftist guerrilla groups united against the military government.

Named after Farabundo Martí, a communist leader executed after a failed 1932 peasant uprising, the FMLN sought to overthrow what they viewed as a U.S.-backed dictatorship.

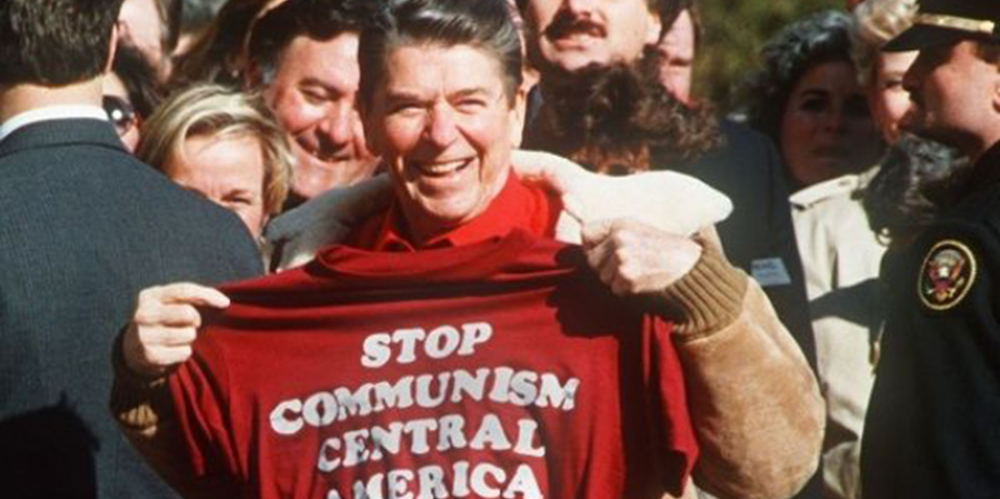

The timing was crucial. The Sandinistas had just triumphed in Nicaragua, and the Cold War was intensifying under President Ronald Reagan.

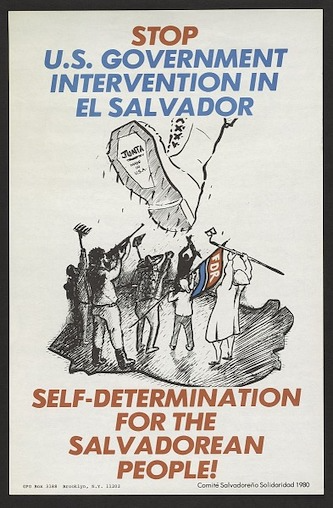

Washington viewed El Salvador through the lens of Soviet expansionism, not indigenous social revolution.

America’s Proxy War

The Reagan administration transformed El Salvador into a testing ground for its Central American strategy.

Between 1981 and 1992, the United States provided over $6 billion in military and economic aid to successive Salvadoran governments, making it the largest recipient of U.S. aid per capita in Latin America.

U.S. Special Forces advisors trained Salvadoran troops, while the C.I.A. provided intelligence and coordination.

The School of the Americas at Fort Benning, Georgia, trained hundreds of Salvadoran officers, including many later implicated in human rights abuses.

The strategy focused on defeating the insurgency through counterinsurgency warfare, which often meant targeting civilian populations suspected of supporting the FMLN.

Death squads operated with impunity, killing anyone deemed subversive — union leaders, teachers, priests, and peasant organizers.

The Human Cost of Cold War Politics

The war’s brutality shocked even hardened observers. The Truth Commission for El Salvador, established after the war, documented over 75,000 deaths and 8,000 disappearances.

Eighty-five percent of the violations were attributed to government forces and death squads.

The 1981 El Mozote massacre exemplified the conflict’s horror. Salvadoran troops trained by U.S. advisors killed nearly 1,000 civilians, including hundreds of children, in the village of El Mozote.

For years, the Reagan administration denied the massacre occurred, despite overwhelming evidence.

Archbishop Óscar Romero [Luce Index™ score: 95/100], who advocated for the poor and criticized U.S. military aid, was assassinated while celebrating Mass in March 1980.

The Archbishop’s killer was trained at the School of the Americas. Romero’s murder galvanized international opposition to U.S. policy in El Salvador. He was said to have been paid by “the fourteen families.”

The 1989 murders of six Jesuit priests, their housekeeper, and her daughter by an elite Salvadoran army unit further exposed the war’s brutality. The officers responsible had received training from U.S. advisors just months before the killings.

Solidarity and Resistance in America

Back in New York, those fake subway tokens represented a broader solidarity movement that challenged U.S. policy in Central America.

Churches provided sanctuary to Salvadoran refugees, activists organized protests, and Congress repeatedly attempted to cut military aid.

The sanctuary movement emerged as religious congregations declared themselves safe havens for Central American refugees fleeing violence.

By 1987, over 500 congregations participated, directly defying U.S. immigration policy that refused to recognize Salvadorans as legitimate refugees.

Witness for Peace organized delegations to El Salvador, bringing back firsthand accounts of U.S.-funded violence.

These testimonies contradicted official State Department claims about progress in human rights and democratic reforms.

The War’s End and Lasting Legacy

The Cold War’s end fundamentally altered the conflict’s dynamics. Soviet support for Cuba and Nicaragua diminished, while the FMLN faced pressure to negotiate. Simultaneously, the U.S. Congress grew increasingly critical of military aid following the Jesuit murders.

The Chapultepec Peace Accords, signed in Mexico on January 16, 1992, officially ended the war. The agreement included land redistribution, human rights reforms, and the FMLN’s transformation into a political party.

Yet Peace Remains Elusive

El Salvador today suffers from endemic violence, with gang warfare and drug trafficking creating murder rates exceeding wartime levels. Many observers trace current violence to the war’s legacy — the proliferation of weapons, institutional weakness, and social trauma.

The United States never fully acknowledged its role in prolonging the conflict or the civilian suffering its policies enabled. El Salvador serves as a cautionary tale about the human cost of Cold War interventions and the long-term consequences of prioritizing geopolitical calculations over human rights.

Those counterfeit subway tokens, small acts of solidarity in a distant city, remind us that even the most remote conflicts touch ordinary lives — and that ordinary people have the power to resist policies they find morally unacceptable.

El Salvador’s Forgotten War and America’s Hidden Role (Aug. 3, 2025)

Summary

El Salvador’s civil war from 1979 to 1992 killed 75,000 people in a conflict fueled by Cold War politics. The United States provided over $6 billion in aid to government forces, enabling widespread human rights abuses including massacres and death squad killings. American solidarity movements, symbolized by activists selling fake subway tokens in New York to fund the opposition, challenged U.S. policy throughout the conflict.