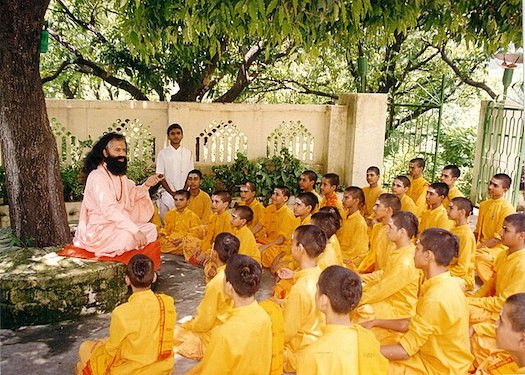

Guru-Shishya Parampara (the teacher-student tradition) included studying arts such as sculpture, poetry and music.

New York, N.Y. — “Guru” is a Sanskrit term for a “mentor, guide, expert, or master” of certain knowledge or field. In pan-Indian traditions, a guru is more than a teacher: traditionally, the guru is a reverential figure to the disciple (or in Sanskrit, literally seeker of knowledge). A guru is one’s spiritual guide, who helps one to discover the same potentialities that the guru has already realized.

The oldest references to the concept of guru are found in the earliest Vedic texts of Hinduism. The guru, and gurukula – a school run by guru, were an established tradition in India by the 1st millennium BCE, and these helped compose and transmit the various Vedas, the Upanishads texts of various schools of Hindu philosophy, and post-Vedic Shastras ranging from spiritual knowledge to various arts.

By about mid 1st millennium CE, archaeological evidence suggests numerous larger institutions of gurus existed in India, some near Hindu temples, where guru-shishya tradition helped preserve, create and transmit various fields of knowledge. These gurus led broad ranges of studies including Hindu scriptures, Buddhist texts, grammar, philosophy, martial arts, music and painting.

In the Advayataraka Upanishad it states, “The syllable gu means darkness, the syllable ru, he who dispels them. Because of the power to dispel darkness, the guru is thus named. (Vrs. 16)

The Bhagavad Gita is a dialogue where Krishna speaks to Arjuna of the role of a guru, and similarly emphasizes in verse 4.34 that those who know their subject well are eager for good students, and the student can learn from such a guru through reverence, service, effort and the process of inquiry.

The 8th century Hindu text Upadesasahasri of the Advaita Vedanta philosopher Adi Shankara discusses the role of the guru in assessing and guiding students.

In Chapter 1, he states that teacher is the pilot as the student walks in the journey of knowledge, he is the raft as the student rows. The text describes the need, role and characteristics of a teacher, as follows:

“When the teacher finds from signs that knowledge has not been grasped or has been wrongly grasped by the student, he should remove the causes of non-comprehension in the student. This includes the student’s past and present knowledge, want of previous knowledge of what constitutes subjects of discrimination and rules of reasoning, behavior such as unrestrained conduct and speech, courting popularity, vanity of his parentage, ethical flaws that are means contrary to those causes.

“The teacher must enjoin means in the student that are enjoined by the Śruti and Smrti, such as avoidance of anger, Yamas consisting of Ahimsa and others, also the rules of conduct that are not inconsistent with knowledge. He [teacher] should also thoroughly impress upon the student qualities like humility, which are the means to knowledge.” — Adi Shankara, Upadesha Sahasri 1.4-1.5

“The teacher is one who is endowed with the power of furnishing arguments pro and con, of understanding questions [of the student], and remembers them. The teacher possesses tranquility, self-control, compassion and a desire to help others, who is versed in the Śruti texts (Vedas, Upanishads), and unattached to pleasures here and hereafter, knows the subject and is established in that knowledge.

“He is never a transgressor of the rules of conduct, devoid of weaknesses such as ostentation, pride, deceit, cunning, jugglery, jealousy, falsehood, egotism and attachment. The teacher’s sole aim is to help others and a desire to impart the knowledge.” — Adi Shankara, Upadesha Sahasri 1.6

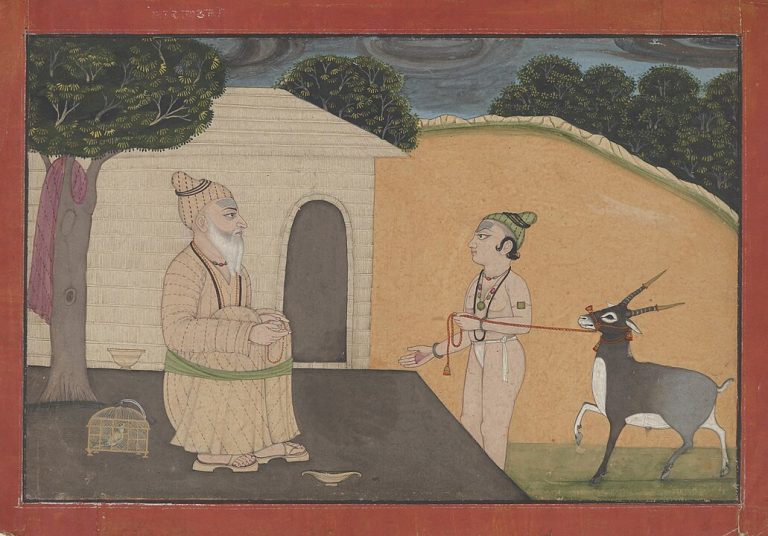

Traditionally, the guru would live a simple married life, and accept shishya (Sanskrit: student) where he lived. A person would begin a life of study in the Gurukula (the household of the guru). The process of acceptance included proffering firewood and sometimes a gift to the guru, signifying that the student wants to live with, work and help the guru in maintaining the gurukul, and as an expression of a desire for education in return over several years.

At the Gurukul, the working student would study the basic traditional vedic sciences and various practical skills-oriented shastras along with the religious texts contained within the Vedas and Upanishads. The education stage of a youth with a guru was referred to as Brahmacharya, and in some parts of India this followed the Upanayana rites of passage.

The gurukul would often be a hut in a forest, or it was, in some cases, a monastery, called an ashram. Each ashram had a lineage of gurus, who would study and focus on certain schools of Hindu philosophy or trade, also known as the guru-shishya parampara (teacher-student tradition). This guru-driven tradition included arts such as sculpture, poetry and music.

Gender and caste

The Hindu texts offer a conflicting view of whether access to guru and education was limited to men and to certain varna (castes). The Vedas and the Upanishads never mention any restrictions based either on gender or varna. The Yajurveda and Atharvaveda texts state that knowledge is for everyone, and offer examples of women and people from all segments of society who are guru and participated in vedic studies. The Upanishads assert that one’s birth does not determine one’s eligibility for spiritual knowledge, only one’s effort and sincerity matters.

The Advayataraka Upanishad states that the true teacher is a master in the field of knowledge, well-versed in the Vedas, is free from envy, knows yoga, lives a simple life that of a yogi, has realized the knowledge of the Atman (Self). Some scriptures and gurus have warned against false teachers, and have recommended that the spiritual seeker test the guru before accepting him.

Swami Vivekananda said that there are many incompetent gurus, and that a true guru should understand the spirit of the scriptures, have a pure character and be free from sin, and should be selfless, without desire for money and fame.

Georg Feuerstein translated the Kula-Arnava, 13.104 – 13.110, thusly:

- Gurus are as numerous as lamps in every house. But, O-Goddess, difficult to find is a guru who lights up everything like a sun.

- Gurus who are proficient in the Vedas, textbooks and so on are numerous. But, O Goddess, difficult to find is a guru who is proficient in the supreme Truth.

- Gurus who rob their disciples of their wealth are numerous. But, O Goddess, difficult to find is a guru who removes the disciples’ suffering.

- Numerous here on earth are those who are intent on social class, stage of life and family. But he who is devoid of all concerns is a guru difficult to find.

- An intelligent man should choose a guru by whom supreme Bliss is attained, and only such a guru and none other.

A true guru is, asserts Kula-Arnava, one who lives the simple virtuous life he preaches, is stable and firm in his knowledge, master yogi with the knowledge of Self (Atma Gyaan) and Brahman (ultimate reality).

In modern Hinduism, the tradition of reverence for guru continues, but rather than being considered as a prophet, the guru is seen as a person who points the way to spirituality, oneness of being, and meaning in life.[82][83][85]

Interestingly, in Tibetan Buddhism, guru is called lama, as in “the Dalai Lama.”

Exploring the Traditional Guru–Disciple Relationship (Aug. 27, 2014)